IBM, the silent job cutter, stokes worker anxiety, speculation

- The US technology giant will not disclose the total number of its employees who were recently dismissed because of competitive reasons

- The Armonk, New York-based company has about 350,000 staff worldwide

IBM’s new chief executive, Arvind Krishna, has continued an unusual company tradition, refusing to disclose the scale of its latest round of job cuts.

The price: speculation about thousands of positions eliminated in the United States last month, and heightened anxiety among employees.

“Everyone wants to know what the full picture is, but they’ll never get it from IBM,” said James Cortada, who spent decades at IBM and has written books on the company’s culture.

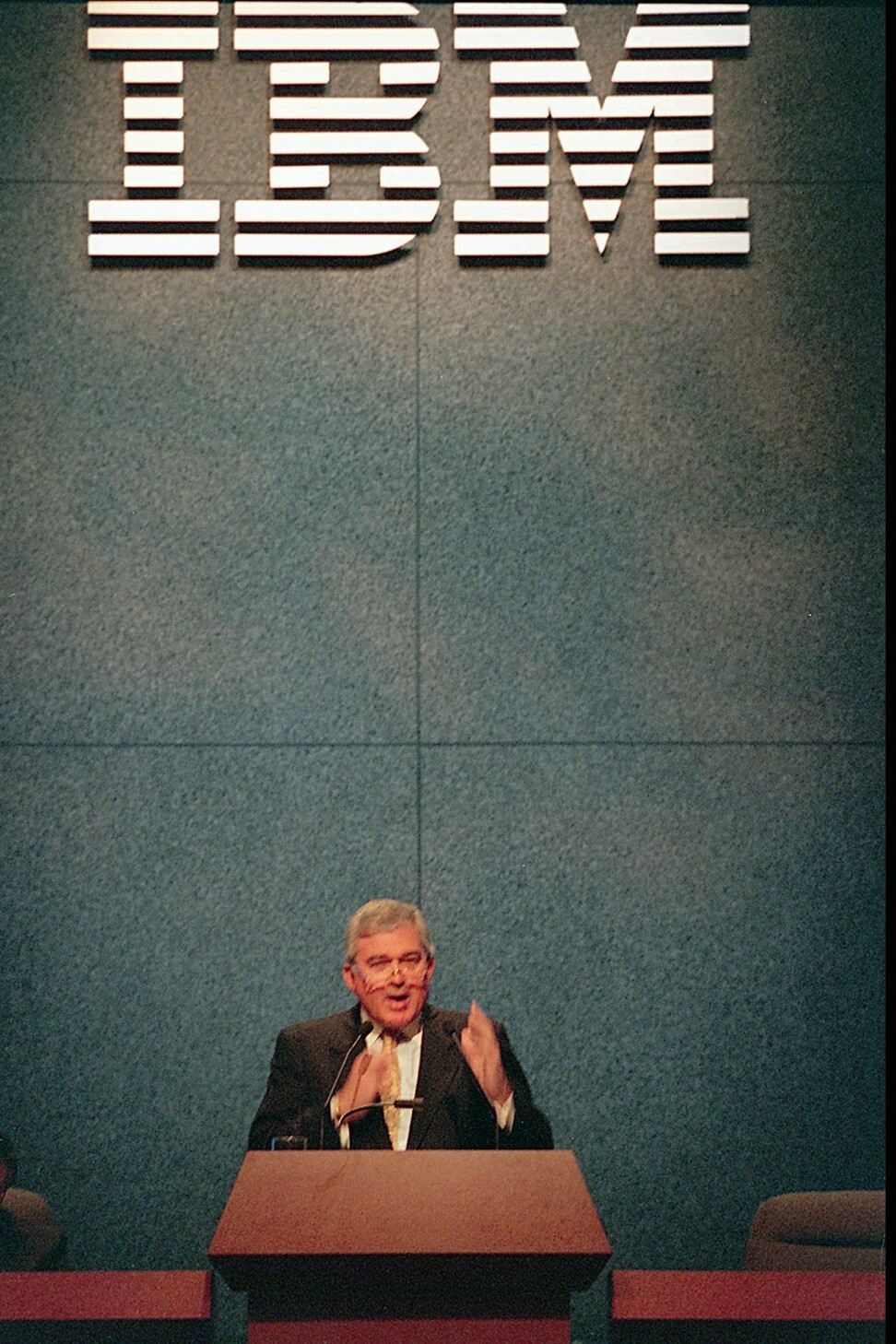

International Business Machines Corp has kept mum on these numbers for decades, with arguably one exception in 1993 when Lou Gerstner, a chief executive hired from outside the company, announced 60,000 dismissals.

When Krishna took the helm in April, Cortada and current employees hoped the new chief executive would use the reorganisation to make his mark and be more transparent as IBM enters its third revolution in 108 years. Instead, Krishna, a company veteran, is sticking to the threadbare script.

IBM spokesman Ed Barbini said the company will not disclose the total number of dismissals for competitive reasons. “IBM’s work in a highly competitive marketplace requires flexibility to constantly remix to high-value skills, and our workforce decisions are made in the long-term interests of our business,” he wrote in an emailed statement. “Recognising the unique current conditions, IBM is offering subsidised medical coverage to all affected US employees through June 2021.”

Many other major tech companies disclose how many employees they eliminate. When HP got a new chief executive last year, the personal computer maker said it would cut as many as 9,000 employees. A few weeks later, Cognizant, an IBM rival, unveiled plans to eliminate up to 7,000 positions.

This year, Uber Technologies, Airbnb and TripAdvisor disclosed painfully large numbers.

“Many companies are firing people today. The more forthright they are about it the better,” said Ronn Torossian, chief executive of communications firm 5WPR, which represents many Fortune 500 companies.

About 90 per cent of the businesses represented by 5WPR disclose a ballpark figure when it comes to large workforce reductions. “It’s a mistake to think you can fire thousands of people and not answer questions,” Torossian said. “And it’s not just the media asking questions – it’s investors, remaining employees and customers as well.”

Eliminating employees is always a sensitive topic. That is especially true for IBM. The company has about 350,000 workers globally, but its domestic workforce has been shrinking while positions have been added in cheaper countries in Asia and Eastern Europe. That exposes the company to criticism and political pressure, especially with US President Donald Trump pushing for more American jobs.

Still, IBM is not alone in grappling with these disclosure questions. Internal battles often arise between company executives, the human resources department and public relations office over how much information to share on job cuts, said Jonathan Segal, a partner at Duane Morris. His general advice: Be transparent.

Everyone wants to know what the full picture is, but they’ll never get it from IBM

“When you don’t disclose, it looks like you’re hiding something, and it can become a bigger story than it otherwise would’ve been,” Segal said. “What employees may perceive is often worse than what it is.”

In the IBM information void, workers are anxiously speculating about the scope of the restructuring. Several affected employees said they asked their managers how many other colleagues lost their jobs and were told they did not have access to that information.

In online forums and private messaging groups, other former and current IBM employees shared snippets of information. Some posts recounted an executive based in Raleigh, North Carolina, telling staff that 20,000 workers were affected. Others said this is IBM’s biggest staff reduction in a decade.

Bruce Baumbush was let go after 22 years with Big Blue. “Half my department is gone,” he said in an interview. “Thousands of people were impacted.”

Watson Health, which offers data-powered medical insights and was once considered an IBM crown jewel, has been “decimated”, according to Baumbush, who worked in artificial intelligence consulting.

Employees in at least eight different states were dismissed, according to interviews with affected IBM workers. Entire teams were cut from the broader Watson business, including managers, these people said. They asked not to be identified discussing sensitive company issues.

Under federal law, corporations must notify regional Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) offices about plans to cut jobs, but there is a lot of leeway for companies to avoid WARN filings.

IBM dismissed 243 employees at three work sites in Costa Mesa and San Jose recently, according to California’s WARN office. Another 42 lost their jobs at an IBM location in the mid-Hudson region of New York State, according to a WARN filing on Friday.

Once the most important computing company in the world, IBM’s star has faded. Newer tech titans such as Amazon.com dominate the growing cloud computing market, while IBM has suffered almost a decade of shrinking revenue.

“All the cloud companies are hiring right now, and IBM is laying people off,” said Ivan Feinseth, chief investment officer of Tigress Financial Partners. “I wouldn’t be surprised about them laying off thousands of people.”

There are no rules forcing companies to announce how many people they hire or fire, the analyst added. “Some companies are very transparent; some companies aren’t.”

In a January earnings call, IBM told analysts it was reorganising parts of the Global Technology Services IT consulting unit, which represents about a third of revenue. The company disclosed a US$900 million restructuring charge.

The changes, followed by Krishna’s appointment as chief executive, represent a new era at IBM: a shift toward a hybrid strategy that connects clients’ data across public and private cloud providers. Last year, IBM closed its biggest deal ever when it acquired open-source software provider Red Hat for US$34 billion to accelerate this initiative.

IBM’s secrecy about job cuts is still guided by the experience under Gerstner in the 1990s, when extra transparency resulted in negative media coverage, employee outrage and litigation, according to a former executive who asked not to be identified discussing private information.