How Huawei beat America’s anti-China 5G propaganda war in Southeast Asia, years before it even began

- Huawei’s 5G technology is under fire in the West, but there is a region of the world where Washington’s anti-China propaganda war was lost long ago: Southeast Asia

- The key to its victory dates back nearly 20 years, to when arrogant Western telecom giants failed to recognise it as a worthy competitor

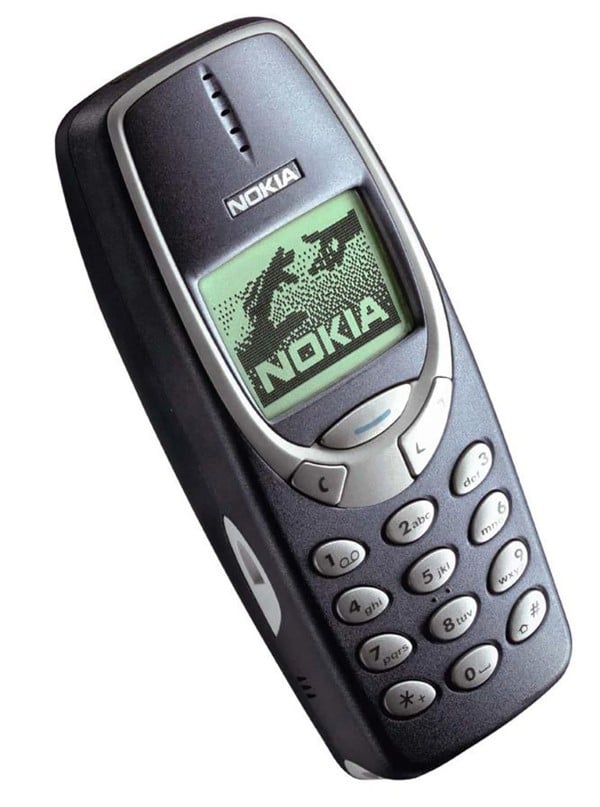

The new millennium is yet to dawn, the internet is in its infancy and Apple’s iPhone is but a distant sparkle in the eye of Steve Jobs. Technology is filling the world with both hope and fear. On one hand, a new generation of pocket-sized handsets, led by the soon-to-be released Nokia 3310, have made mobile phones truly mobile for the first time – offering monochrome visions of the future that pack battery lives of up to 11 days. On the other, the world is gripped by a deep paranoia that a sinister-sounding “millennium bug” will usher in a digital apocalypse.

My way or the Huawei: how US ultimatum fell flat in Southeast Asia

Malaysia welcomes Chinese tech giant Huawei despite Western concerns

Still, there is a corner of the globe where the US has already lost its propaganda war: Southeast Asia. And it did so long ago, back in the days of monochrome mobiles.

HELLO HUAWEI

Key to these early deals, which gave a foothold to Huawei and laid the groundwork for its later success, was its willingness to undercut market leaders still too arrogant to acknowledge the Chinese upstart as a challenger to their dominance.

Don’t ask why US acted against China’s Huawei. Ask: why now?

Koh Chee Koon, an ex-consultant for Huawei who has also worked at Nokia and Ericsson, saw first hand how Nokia and Ericsson, the market leaders of the time, underestimated both the firm and its strategy.

“When Huawei first entered Southeast Asia, it was willing to do a lot more for its customers at a competitive price,” he recalled.

As with Huawei, China thinks it can split the US and EU. It’s wrong

Today, as noted by Koh, the company’s equipment is “no longer cheap”. Having gained traction by undercutting less dynamic competitors, the company has invested its gains wisely, pumping billions into research and development that has helped it to expand its products, services and vision.

“Early on, Huawei naturally focused upon emerging markets where price and financial assistance were high priorities, but when [established carriers] started adopting their technology it was a sign of their growing maturity,” said John Ure, the author of Telecommunications Development in Asia.

Today, Huawei is the world’s largest telecommunications equipment supplier.

A PRIZED MARKET

Its focus on the region is for good reason – Southeast Asia is an inherently attractive market.

UK will talk up Huawei to China, then back the US like always

The region has a largely youthful population of more than 600 million, compared to Europe’s ageing but slightly larger headcount of more than 700 million. More significantly, some 350 million people in its emerging market are already online, with many primarily accessing the internet via a mobile device.

In Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia for example, users spend about four hours a day on mobile internet – twice as long as users in the US and UK, according to a 2018 report by Google and Temasek Holdings.

DEAF EARS

The demand for mobile internet and data means competition is fierce among operators as they vie to offer faster speeds and better data packages to consumers. But the presence Huawei has built up in Southeast Asia over the past 20 years has helped inoculate it from a recent US narrative that has harmed the firm’s prospects in the West.

While the US pressure has had a notable effect on its partners in the Five Eyes intelligence sharing alliance – Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK have all voiced doubts about Huawei, to varying degrees – its concerns have largely fallen on deaf ears in Southeast Asia, even among its treaty allies, the Philippines and Thailand.

Solomon Islands drops Chinese tech giant Huawei for billion-dollar undersea cable, signs Australia

In the Philippines, Huawei’s dominance stems from a US$700 million network modernisation deal it made with the domestic player Globe Telecom in 2010. Today, Globe Telecom’s 4G networks run entirely on Huawei equipment, and the two companies plan to roll out 5G networks across the country in the second quarter of 2019.

Sustaining its dominance is a mix of its technological prowess and scepticism over the US’ claims.

“From a pure technology perspective, Huawei is ahead of its competition,” said Maria Yolanda Crisanto, Globe Telecom’s senior vice-president for corporate communications. “Huawei is a global technology leader with a full range of products to serve our needs [and this is] enjoyed by Globe customers,” she said.

In February, Globe Telecom’s chief executive Ernest Lawrence Cu poured water on the US’ position, saying Huawei had been given a “clean bill of health” by British and Israeli consultants hired to check whether its networks were secure. “They may provide the equipment, but we run the network and so we know what passes over our network, what goes through it … we’re very confident that we’re well protected,” he told Bloomberg.

In Thailand, Huawei already provides 4G network equipment to major telecoms operators like AIS and True. Alongside its rivals Ericsson and Nokia, it has been invited to test 5G equipment in Chonburi, a region the Thai government hopes to develop into a leading economic zone under its Eastern Economic Corridor scheme.

Huang Xiangmo and Meng Wanzhou today, any other Chinese tomorrow?

To be sure, the region isn’t completely unquestioning of Huawei’s motives. The Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company (PLDT) – the largest telecoms company in the country – has vowed to scrutinise Huawei’s involvement in the roll-out of 5G networks by its mobile unit Smart Communications, a rival of Globe Telecom. PLDT has asked Huawei to clarify if it is “able to access data generated by the network”, PLDT chief executive Manuel Pangilinan said in February.

For its part, Huawei has long maintained that it protects the security of its customers’ data and never installs back doors in its equipment or software, as that would be tantamount to “committing [commercial] suicide”.

A BATTLE FOR HEARTS AND MINDS

The days of needing to undercut more established rivals are long in Huawei’s past and – thanks to its world leading technology – it now occupies the kind of dominant position once enjoyed by Nokia and Ericsson in those monochrome days of old.

But what reason is there to believe that one day, it too – much like the once futuristic Nokia 3310 – won’t fade into irrelevance?

Thomas Zhou, a director of Huawei’s public affairs and communications in the region, said that an often overlooked element of its success was the importance it places on winning the hearts and minds of local populations.

It ingratiates itself with communities by investing in social programmes and development initiatives, grooming local talent and building local laboratories that provide jobs and contribute to developing economies.

British universities wrestle with anxiety over links to Chinese tech giant Huawei: investigation

Huawei Malaysia, for example, in 2015 set up a programme with Telekom Malaysia and Celcom Axiata to provide US$121,000 worth of disaster relief to communities affected by flooding on the east coast. Similar programmes across the region help to strengthen the firm’s relationships with governments and local communities, Zhou said.

But ultimately, Zhou said, Huawei’s leadership in the region should be attributed to something the firm champions as its core value: putting customers at the heart of everything it does.

“Whenever natural disaster strikes, Huawei engineers are always the first to be at the disaster site, to help operators restore telecom services,” he said.

“Few other companies can claim to do the same.” ■

Additional reporting by Raissa Robles and Li Tao

This story has been updated to more accurately reflect Thomas Zhou’s comments on Huawei’s social programmes.