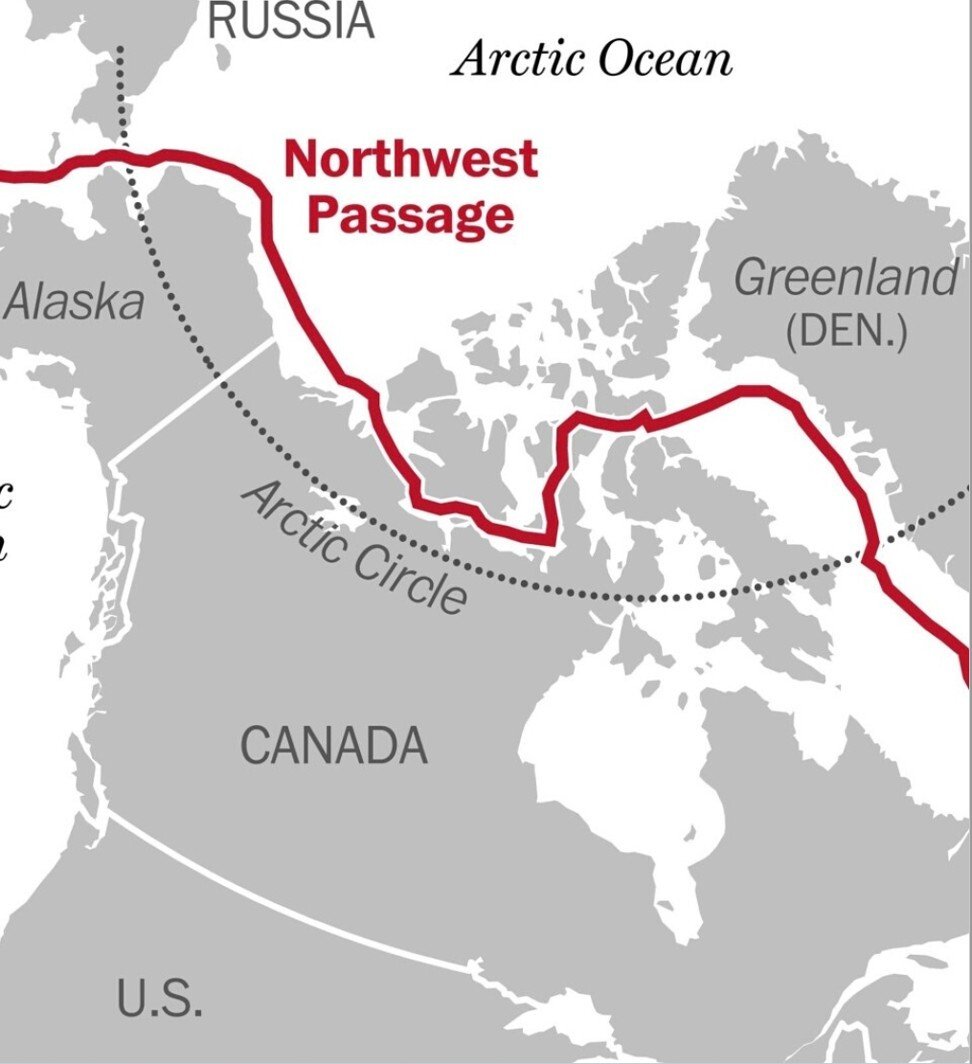

The first black person to row an ocean eyes Northwest Passage for second historic voyage to inspire fellow Caribbeans

- Philip Als makes history in 2003 by crossing the Atlantic and now wants to inspire Caribbean people all over again with world first Arctic row

- ‘We are all human beings, you can achieve anything,’ Als says in October during Black History Month

Philip Als is already a history maker, but 17 years after he first entered the record books he is intent on transcending human boundaries all over again.

In 2003, Als became the first black person to row across any ocean when he crossed from the Canary Islands to Barbados with partner Randal Valdez.

“People have seen the film of the Jamaican bobsleigh team, Cool Runnings,” Als said at the start of October – which is Black History Month. “So it has been established on land. But this is the sea version, too. People from here need guidance and focus. I want to tell them the sky’s the limit. You can do whatever you want if you apply yourself. White, black, it doesn’t matter, we are all human beings.”

Als believes the key to success will be looking after each other in the Passage.

“We have to take care of each other, that’s a very important thing,” he said. “If we don’t, then we have to do double the work as you have to pick up the slack. If you find a day when you can do a little bit more, you should and let your partner rest. You have to be family.”

“In terms of weather and water, no one can say what it will be. When nature turns, it changes in a millisecond,” Als said. “You have to be flexible, you have to be cautious and you have to adapt. You have to be a chameleon.”

Als’ voyage in 2003 paved the way for other Caribbeans to make the crossing. He called the expedition “Rowing Home”, but getting to the start line was just as tough.

He first tried to organise a team to cross in 1997, but his partner was involved in a microlight crash. His next partner, set for 2003, was not comfortable at sea.

“He couldn’t even tie his shoelaces, he had no boating experience at all. I was trying to coach him but it was like talking to a stone,” Als said. “About six months before, he pulled out. It brought tears to my eyes because he put so much effort in, but he wasn’t the person to risk your life with.”

Luckily, Als had anticipated the drop out and Valdez had already been training. So the pair were ready to go and travelled to the Canary Islands to be part of the Atlantic race.

“I was the first Caribbean, Barbadian, black man, person from this neck of the woods, to cross the Atlantic. Well, voluntarily, but that was before my time,” he said.

“When we got to the Canary Islands, everyone was saying, who is this Barbados team? They were rowers and came from rowing clubs. But we had some parties, we shared rum from Barbados, and we became friends,” Als said.

The other teams, with their rowing backgrounds and state-of-the-art boats, underestimated Als and Valdez. Als had been a professional windsurfer, one of the first black people on the world circuit, and Valdez was a top-class dingy sailor.

“We were rowing home. If you want to get to Barbados, you need to beat us. All the other teams that were fit and had the fancy equipment, that didn’t help because they didn’t know the ocean like us. We got out there, said our prayers to the Almighty and then we let those oars rip.”

The pair finished third, after 43 days.

“In the middle of the ocean, I knew that it would be like a poker hand. You have to go with what you are dealt. You cannot change your hand in the middle of the game,” Als said.

“In the first two weeks, we had issues and the currents were pushing us back. We had to deploy the sea anchors. It was very hard and after two weeks I felt like saying ‘I don’t want to do this any more’, and ask for help. But quitting never crosses your mind.

“I spent two years spending my time trying to get people to believe in me, sponsor me. There were many people who were sceptical, nonbelievers. So we would never quit.

“I just wanted to do it and inspire people from the Caribbean region. When you hear about swimmers, rowers, sailors, you hear about Europeans and white people,” Als added. “But when you are dealing in sport, everyone is like brothers and family.”