- No winner in 1919 Stanley Cup as Seattle Metropolitans and Montreal Canadiens series called off before deciding game

- AFL, MLB and English football among sports to ignore the global pandemic and carry on regardless

Boxing postponed, hockey cancelled and football behind closed doors. That might sound familiar in these largely sport-free days but it is how the sporting world was affected by the Spanish flu pandemic a century ago.

The H1N1 outbreak, the same strain as the swine flu of 2009, was first recorded in 1918 and lasted until late 1920, with a more virulent second wave peaking in October 1918, the pandemic’s deadliest month.

It did not come from Spain, although the country’s king, Alfonso XIII, was one of the most high profile infected and as a neutral country during the First World War there were also no limits on reporting there. Experts still debate its source, with its spread exacerbated by the movement of troops overseas and increased global travel.

What is not open to debate is that the “Spanish Lady” or the “Blue Death”, a name given on account of turning victims’ lungs blue, left a trail of devastation in its wake. Some 500 million people, a third of the global population, were infected and, at the top end, estimated deaths numbered 100 million. The sporting world did not escape this pneumonic influenza.

The 1919 Stanley Cup between the Seattle Metropolitans and Montreal Canadiens was eventually abandoned before game six on April 1. The players had battled through five games but the fifth had seen Canadiens defenceman Joe Hall collapse on the ice.

With less than six hours before the puck was set to drop on the decisive game six in Seattle, the series was called off with Hall, four of his teammates and the team’s manager hospitalised. The hosts had two players and their manager in hospital, too.

Three-time Stanley Cup winner and married father-of-three Hall died in the Columbus Sanitorium on April 5, aged 37.

The cup itself marks the 1919 edition with “Series Not Completed”, which was the first time it did not have a winner until the 2004-05 lockout.

Elsewhere in the US, college football saw many teams forced into truncated 1918 seasons because of a combination of rises in the Spanish flu that autumn and losing players to military call-ups.

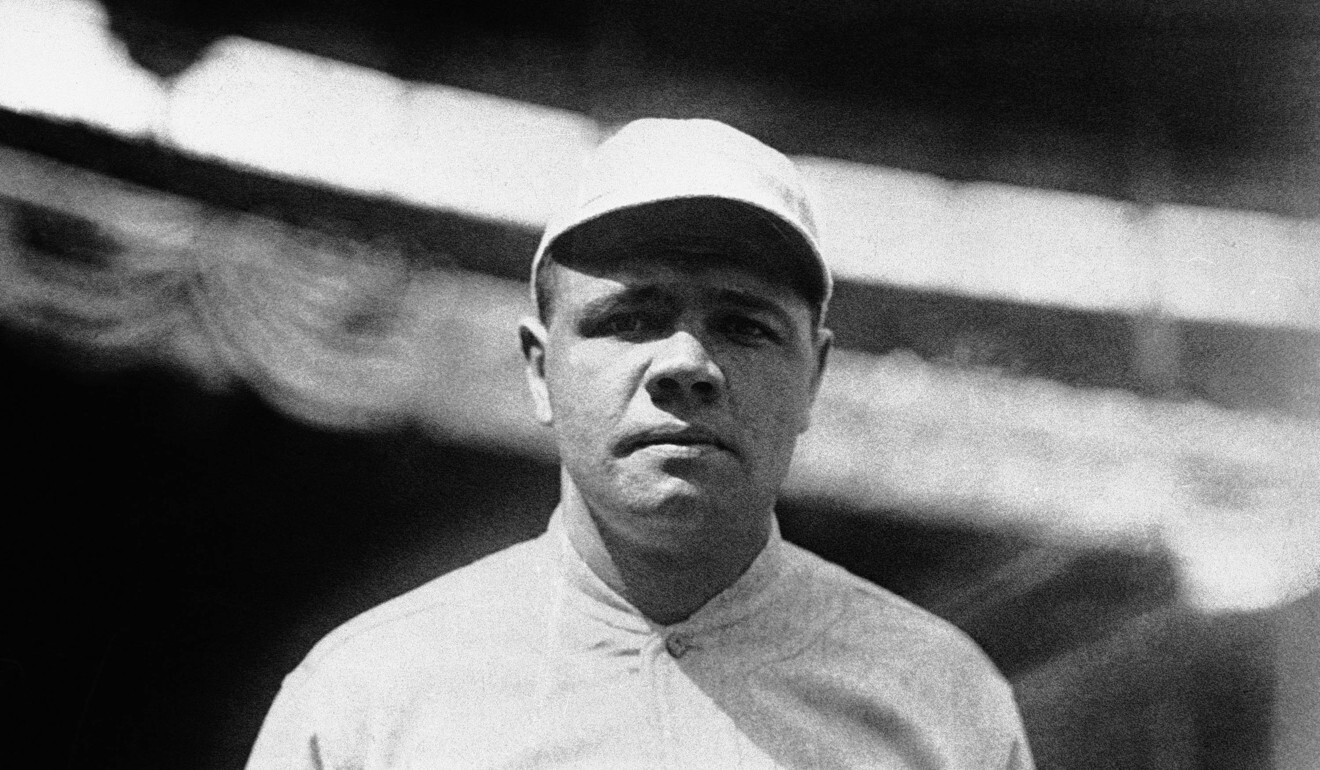

Major League Baseball was one sport to press on, but it lost a number of high-profile players among the dead. Boston Red Sox legend Babe Ruth was said to have caught the Spanish flu twice, beating it but only just.

“Rumours shot through Boston that ‘the Colossus … worth more than his weight in gold’ was on his deathbed,” wrote Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith in War Fever: Boston, Baseball, and America in the Shadow of the Great War.

Ruth guided the Red Sox to the 1918 World Series over the Chicago Cubs, despite warnings against the series going ahead that September because of the risk of further infections. Baseball played shortened seasons in 2018 and 2019 but because of the war.

Boxing’s headline heavyweight clash between Jack Dempsey and Battling Levinsky was postponed from October to November, once restrictions on crowds in Philadelphia had eased, but the sport had carried on regardless during the pandemic.

“Quarantine order hits all sports except duck hunting,” was a headline in The Los Angeles Daily Times on October 12, 1918, that matched the peak, but across the world several sports essentially pressed on.

In Australia, the Victoria Football League (the precursor to the AFL) not only carried on but was more successful than in previous years.

“The-then Victorian Football League (VFL) actually expanded during the influenza emergency,” AFL.com says. “After being reduced to an all-time low of just four teams and 12 rounds at the war’s horrific peak in 1916, the VFL returned to a full complement of nine teams and 18 rounds in 1919.

“There weren’t any crowd restrictions in place either, so most games attracted fans in their thousands – albeit in slightly reduced numbers due to the flu scourge, although the finals still drew an average crowd of 47,000 – a six-year high.” The AFL website also says no players died but several former stars were among the victims.

In Ireland, the All-Ireland Gaelic football final was postponed from 1918 to the following February with Wexford beating Tipperary at Croke Park, despite missing top scorer Davy Toibin through sickness. In August 1918, crowds defied the British to watch Gaelic Sunday.

“Over 50,000 people across Ireland played Gaelic games in a peaceful, organised protest that Sunday, an act that ultimately saw an end to the requirement of a licence to play a GAA match,” wrote Irish broadcaster RTE of the historic day that came during a lull in infections.

In Spain, Barcelona founder Joan Gamper led the fight to allow football to carry on. The Spanish Football Federation had called the sport off, but the Catalan championship started anyway in October, 1918. Spanish football newspaper Marca reported that Gamper led a commission that convinced the Spanish Health Ministry to allow football to proceed, just as athletics and tennis had.

The British parliament never actually cancelled football for the pandemic, nor did it limit crowds. Chelsea played to more than 20,000 at Stamford Bridge. This was despite the Football League and FA Cup being cancelled for the war – instead, teams played in regional competitions with Chelsea in the London Combination League.

As Chelsea recorded on their official website, several of its players were infected but recovered. However, former player Angus Douglas, who had since become a Newcastle United player, died that December, aged 29.

Women’s football was at its peak, with many teams stepping into the gap left by the absence of the league and cup. The Dick, Kerr Ladies team, named after the Preston factory where the players worked, played throughout the years of the pandemic and often to large crowds.

At no point were either men’s or women’s games played behind closed doors and the Football League resumed as normal in September 2019. This mentality was not limited to sport. There was a British General Election in December 1918 and London’s theatres carried on regardless, posting record takings.

As Laura Spinney wrote in her 2017 book Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World, the flu had lasting implications.

“The flu resculpted human populations more radically than anything since the Black Death,” she writes. “It influenced the course of the First World War and, arguably, contributed to the second. It pushed India closer to independence, South Africa closer to apartheid, and Switzerland to the brink of civil war.”

Not all of them were negative, she concluded.

“It ushered in universal health care and alternative medicine, our love of fresh air and our passion for sport.”

Times are very different, the world is more globalised and sport is bigger than ever, but the last of those seems the most likely lasting impact of the coronavirus pandemic.