2022 Winter Olympics: Beijing risks backlash as athletes find powerful voice

- Chinese Communist Party is feuding with many countries, high among them Winter Olympics heavyweights the United States, Canada and Sweden

- The Games in Beijing will likely be complicated by worsening geopolitical tensions over the next two years

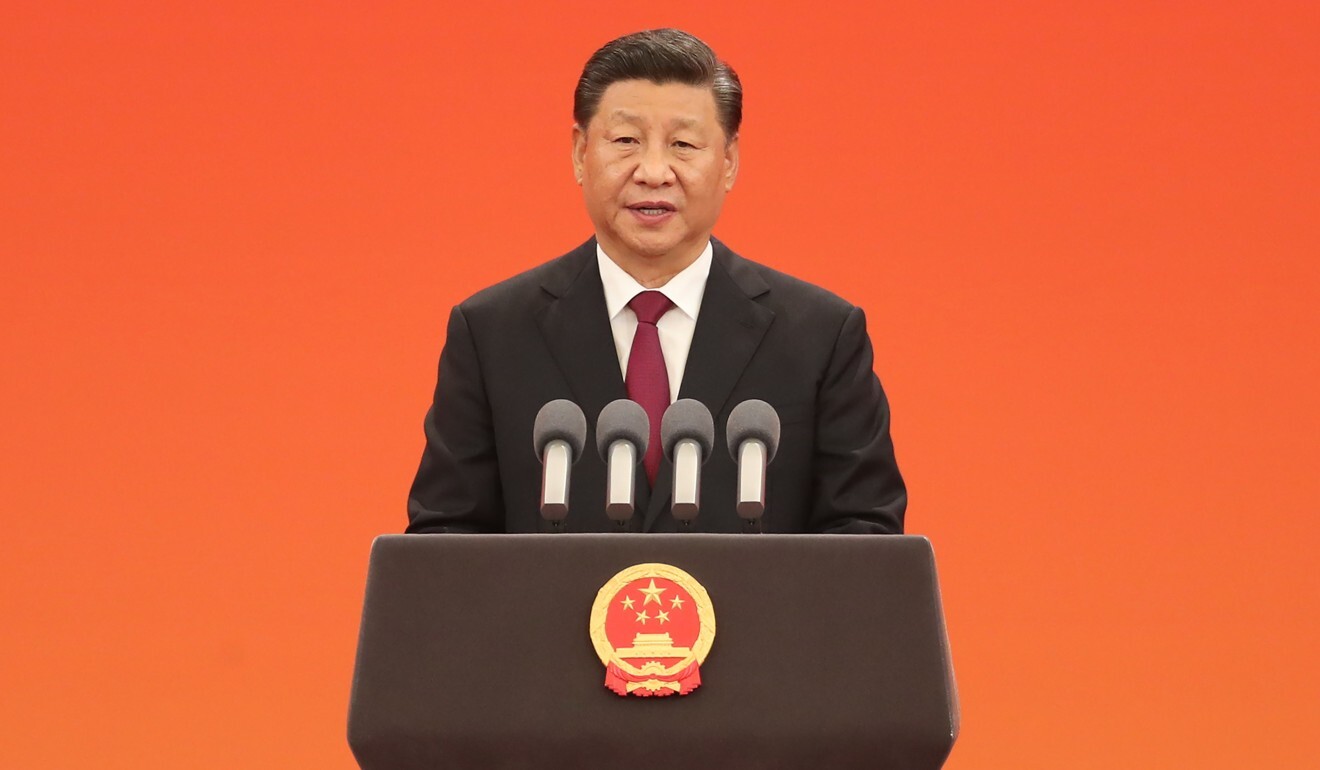

Will China’s growing geopolitical isolationism with a number of high-profile nations bring about a boycott of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics in two years’ time?

Athletes have found they can get traction making political statements, be it taking a knee or raising a fist, and no nation is more well known for crushing dissent than China.

How it is all going to fly in the world’s biggest authoritarian regime in two years’ time is anyone’s guess.

Boycotting the Winter Olympics is going to become a hot topic, one that will be supercharged if and when Japan finally pulls off the 2020 Summer Olympics next year. There is no shortage of digressions to choose from if athletes or countries want to make a statement, the most telling being China’s alleged human rights abuses of Uygur minorities in Xinjiang province.

There is also a health factor that will come into play as we may now be living in an ongoing, never-ending pandemic. Travelling internationally is going to be difficult for years to come, which will alter the sporting landscape and force countries and athletes to make tough decisions about the events they plan on hosting or attending.

The National Basketball Association’s love affair with China appears to be over after an international crisis was whipped up via a tweet last year by Houston Rockets general manager Daryl Morey in which he posted support for the Hong Kong protesters.

Tencent still doesn’t plan on showing Rockets games when the NBA looks to resume its season on July 30, and CCTV, the state’s public broadcaster, appears not to be budging on blacklisting the entire league.

In Australia, concerns mount that China could use TikTok to spy on users

Smith tweeted that World Athletics should axe the Diamond League track and field stop in Shanghai in September, claiming Beijing’s controversial national security law constitutes a human rights violation in Hong Kong.

Smith’s tweet is odd given he seems to have no connection to the issue, but the fact that World Athletics responded is even more telling.

“If World Athletics changed its competition hosts based on shifting political landscapes it would become impossible to maintain a global sporting calendar for our athletes, and a community of 214 member federations,” it said in a statement on Inside the Games.

A large chunk of China’s geopolitical future rests on the upcoming US election. Four more years of Trump, and one in which he no longer needs to worry about re-election, could spell disaster for US-China relations. Without an overarching calm between the world’s biggest heavyweights, it leaves little room for other players to write positive narratives with China.

When Beijing won the right to host the Games in 2015, it was a noteworthy decision as it will become the first to host a Summer and Winter Olympics. It wowed the world in 2008 with its spectacular opening ceremony, ushering in what many thought was a new modern era for China and the nation’s coming out party after a long period of isolationism.

However, 2015 feels like another era. China has since made more enemies than friends and the authoritarian regime is showing no signs of changing its tune.

Boycotts in the modern Olympics are nothing new, they date back to 1936 in Berlin during the Nazi regime. But there hasn’t been a wide-scale one since 1984 during the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union, in response to an even larger one in 1980 in Moscow.

If 2020 has taught us anything, the universe is well equipped to drop black swans in succession. No one knows where China will stand in two years’ time when athletes and nations will decide if sport still trumps politics.

But if history is any indication when it comes to geopolitical tensions, things tend to get a lot worse before they get any better.