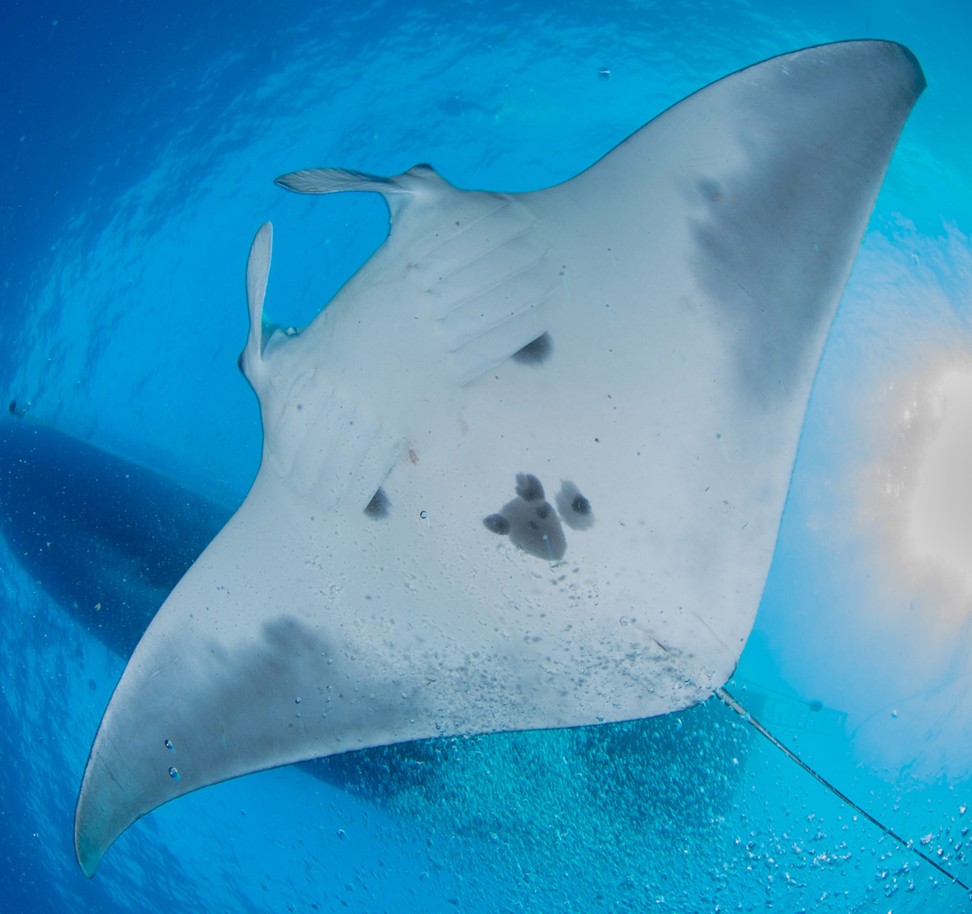

Scientists discover world’s first known manta ray nursery

A reef system in the Gulf of Mexico helps answer a question that has long puzzled marine biologists – where are the baby manta rays?

The University of California, San Diego has discovered the world’s first known nursery for manta rays, an idyllic spot in the Gulf of Mexico where the “gentle giants” approach divers along colourful reefs that seem drawn from the imagination of Walt Disney.

An exploration team led by Josh Stewart, who is finishing up his doctorate in marine biology at the university’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, made the discovery and confirmed its importance over the past few years.

He was aided by colleagues from NOAA who manage the site, which is part of the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuaries, about 115km south of Galveston, Texas.

Stewart has been trying to solve the mystery for years, and had some initial success in 2016 when he saw a juvenile oceanic manta ray (Mobula birostris). He later saw more juvenile mantas and, with help from the NOAA researchers, determined that he’d happened upon a nursery. The discovery was published this week in the journal Marine Biology.

The juveniles were largely found in an area when the sea floor slopes into deeper water.

“We think they may be feeding on specific types of zooplankton there, then migrating up toward the surface, where we saw them,” Stewart told the San Diego Union-Tribune. “They might be hanging around the banks because it could be a little safer than open water.

“We’ve seen them so rarely (in the past) that we know very little about these juveniles. We don’t know how far they move, or exactly what they feed on, or all of the habitats these access.”

But Stewart can say with certainty that simply hanging in the water, waiting for manta rays to arrive, is a remarkable thing to experience.

“You’re out there, doing your work, and you look up and there’s the distinctive shape of a manta,” Stewart said. “At first, you can barely see it. But then it comes into view and my heart skips a beat. (The adults) are gigantic. They can have a 21-foot (6.4-metre) wingspan. And they’re super-friendly. They’ll get really close to you.

“That makes them a lot different from other large marine species, who keep their distance. Mantas are curious. They’re interested in why divers are blowing bubbles. They’ll hang out. I can’t think of another large animal that will do that with you.”