Transparency International: China climbs two places in global corruption perception ranking as President Xi Jinping wages war on graft

Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index was released on Wednesday

China has moved up two places in a global corruption index of the world’s nations as President Xi Jinping waged a high profile war on graft that has netted thousands of officials.

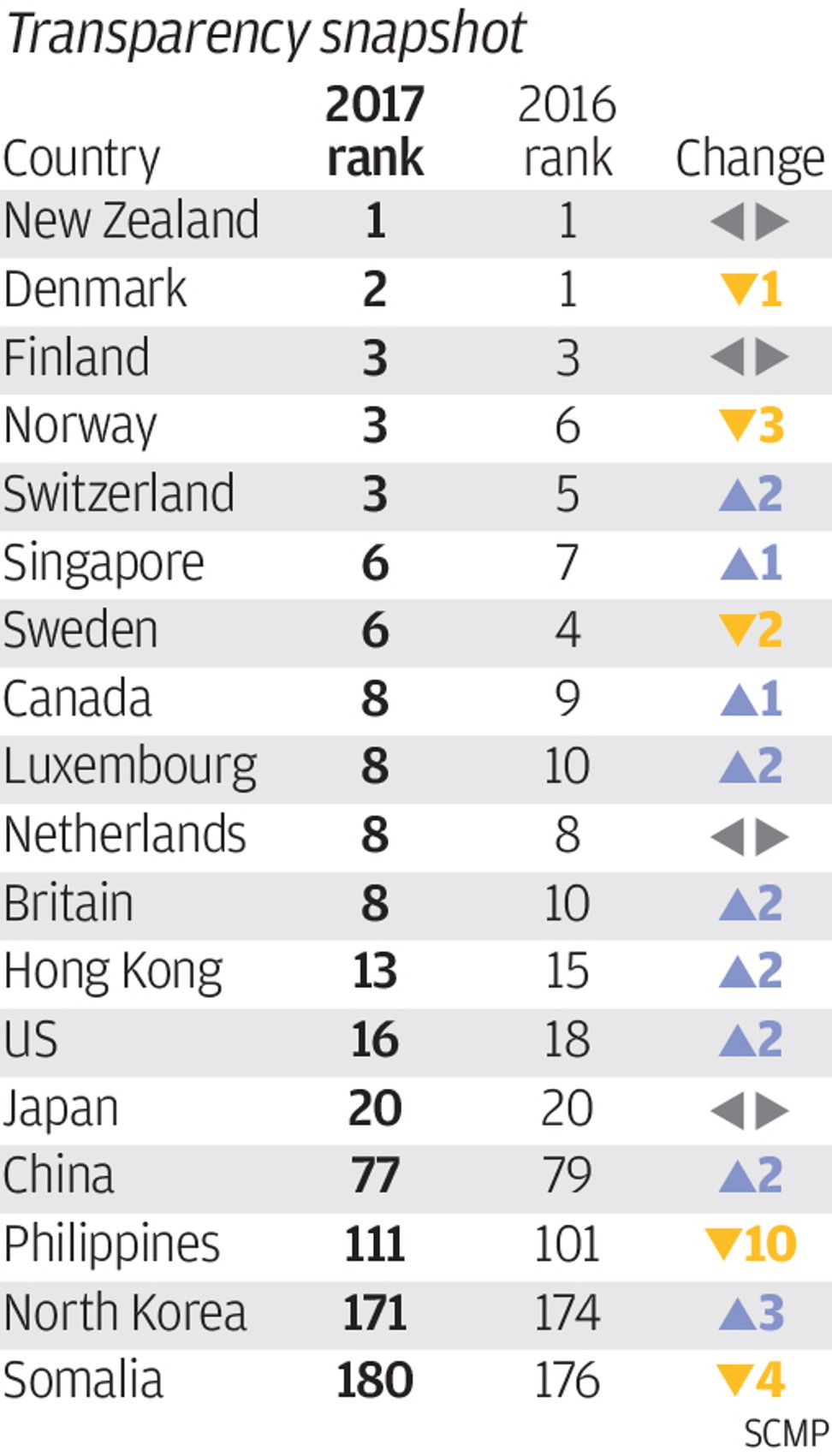

Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2017 was released on Wednesday, showing very little change among the largest nations’ standings, and more than two thirds of all 180 participating countries with a score of less than 50 – out of a possible 100.

Leading the rankings, which are now in their 25th year and measure public sector corruption, was New Zealand and Denmark.

Hong Kong climbed two places to 13th position, with a score of 77, and mainland China edged up two places to 77th, but kept a low score of just 41.

Singapore improved its position by one, to reach 6th place, Japan stayed at 20th position, the US climbed two places to 16th position and the UK edged up to 8th spot.

But these marginal improvements in the rankings masked a more concerning trend in the overall scores, according to Alejandro Salas, senior expert on the Asia-Pacific region at Transparency International.

For example, he said Singapore’s score had fallen three points since 2012, while Japan and the US had barely moved.

India, like China, was stuck at 40, and Australia has declined from the 85 it reached in 2012 to 80 in 2014, and now 77.

“If countries continue doing minimum and isolated efforts, say signing international anti-corruption agreements or conducting some arrests and prosecution of individuals, they will fulfil the purpose of showing through media headlines that they are active in the anti-corruption front.

“However, that is far from being a sustained and impactful holistic approach,” he said.

Xi launched his sweeping crackdown on graft when he first came to power five years ago, and has so far disciplined officials from the highest ranks of the Communist Party and military, for graft or disloyalty.

Shaun Rein, managing director of China Market Research and author of The War for China’s Wallet: Profiting from the New World Order, said Beijing’s crackdown was having a largely positive effect, albeit with two consequences.

“Government officials are scared of green lighting bigger projects so business transactions have slowed,” he said.

“Officials are scared of getting fingered for being corrupt so it is easier to keep their heads down and not approve anything.”

“[And] in general the speed of business is slowing because of the bureaucracy and policies being implemented. For example, before one could bribe an official to get approvals for a real estate project. Now they have to follow a transparent bidding and approval system.”

But it is not so much the catching of officials – Chinese or elsewhere – that frustrated Transparency International’s Salas, who called for better press freedom to cover and examine corruption cases.

“Each country is different, so for example China has to do more beyond punishing some individuals,” he said.

“It has to allow journalists and activists to raise their voices, while the US has to urgently control the money that flows to politics from big businesses, and so on.”

According to data from the Committee to Protect Journalists, more than 9 out of 10 journalists were killed in countries that scored 45 or less on TI’s index over the past six years. And one in five of those dead journalists were covering a story about corruption.