Ireland prepares to vote on whether to lift decades-old abortion ban - and emotions are running high

The referendum comes three years after Ireland backed legalising same-sex marriage by a landslide – a seismic change for the once devout country

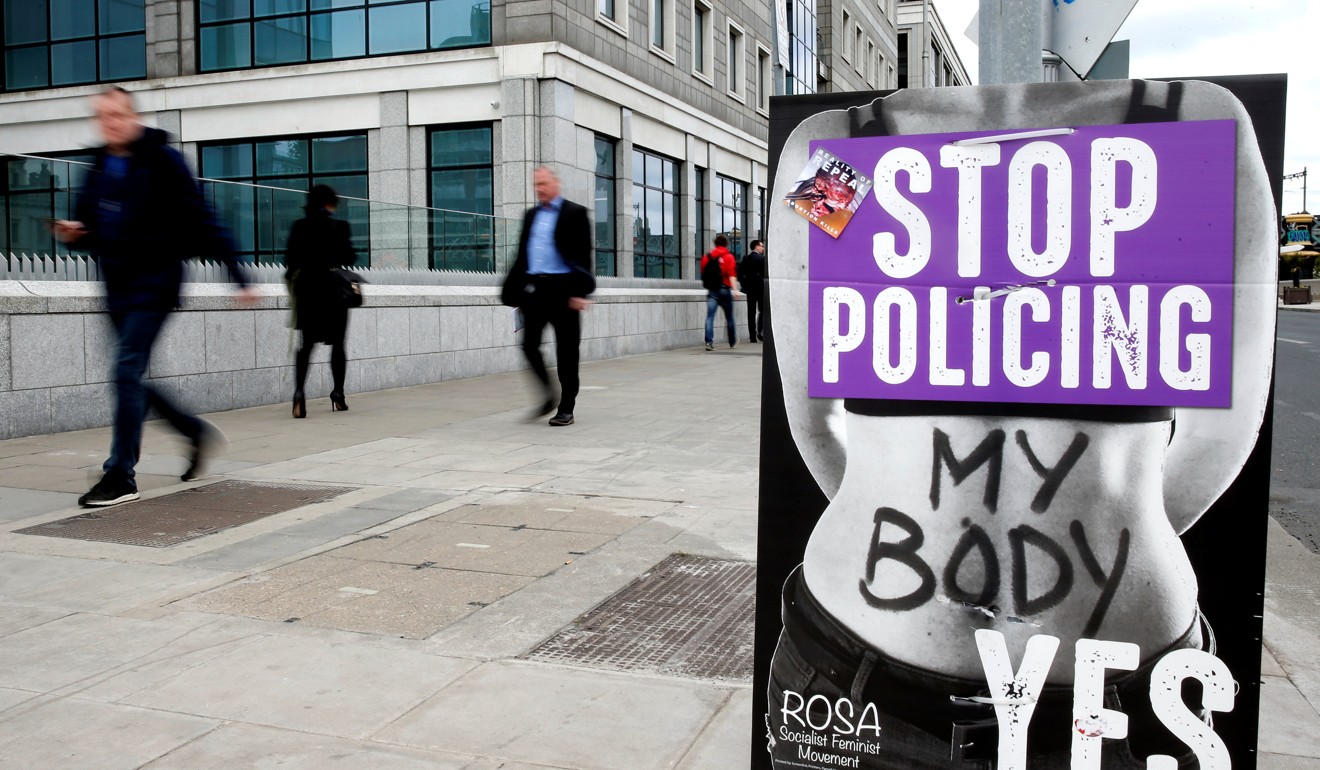

Posters for and against abortion are plastered all across Ireland as the campaign ahead of a historic referendum Friday in this mainly Catholic nation turns increasingly testy in its final days.

Voters head to the polls to decide whether to repeal a constitutional ban on all abortions except in cases where the mother’s life is at risk.

Recent opinion polls have put the “Yes” camp ahead, but its lead has narrowed in some surveys, while around one in six people remain undecided.

“The depth of feeling on both sides has been very apparent,” Diarmaid Ferriter, lecturer in modern Irish history at University College Dublin, said.

The referendum comes three years after Ireland backed legalising same-sex marriage by a landslide – a seismic change for the once devout country.

Ferriter said that while the run-up to the 2015 vote was “positive and uplifting”, the campaign ahead of the abortion poll was “much more visceral and deep-rooted”.

A 1983 referendum approved outlawing abortion by a wide margin, but on a turnout of just over half the voting population.

Subsequent legislation ruled anyone having an abortion could face 14 years in jail.

The law has led to thousands of women travelling each year to Britain where abortion is legal.

It was tweaked in 2013 to allow terminations if the mother’s life is at risk, following public outrage at the death of Savita Halappanavar, a pregnant woman originally from India who was refused an abortion.

Impetus for the new ballot also came from the case of Amanda Mellet, who was forced to travel to Britain for an abortion after she suffered fatal fetal abnormality.

Mellet took her case to the UN’s Human Rights Committee, which ruled that denying her a termination in Ireland was a denial of human rights.

The Irish government offered her 30,000 euros (US$35,000) in compensation – further spurring calls for reform.

Proposed legislation to follow any repeal would allow unrestricted abortions up to 12 weeks, with some exceptions up to six months in certain defined circumstances.

Months of campaigning has become increasingly testy.

Earlier this month Prime Minister Leo Varadkar, who backs the “Yes” campaign, denounced the pro-life lobby for using images of people with Down syndrome and suggesting repeal would lead to terminations of babies with the genetic disorder.

Television debates have been criticised for descending into point-scoring, while medical professionals taking a stance have been assailed.

“No” campaigners have claimed a biased liberal mainstream media is in cahoots with the “Yes” lobby and, with a majority of Irish MPs backing repeal, they pit themselves as anti-establishment with the slogan: “Join the rebellion”.

Decisions by tech titans Google and Facebook to halt referendum adverts reinforced their suspicions of being silenced in a “rigged” vote.

Meanwhile the Catholic Church has largely taken a back seat in the campaign – mindful, according to experts, that an overly dogmatic approach could have the reverse effect of encouraging a pro-abortion vote.

According to a 2016 census 78 per cent of Ireland’s 3.7 million people declared themselves Catholic, but numbers attending weekly mass have been steadily falling.

“I think the debate back then was dominated by a lot of older voices and a lot of male voices, and the Church was obviously in a much more powerful position than it is today,” he said.

“There’s a much younger profile to the campaigners on both sides.”

Youthful activists from both sides have hit the streets and social networks to mobilise the divided electorate.

The “Yes” campaign successfully promoted various hashtags including one – #hometovote – encouraging overseas voters to return for the poll.

Bursaries have been set up at universities in Cambridge, Oxford, London and Nottingham in England to help Irish students fly home for the vote.

They also harnessed popular stars, including actors Saoirse Ronan, Andrew Scott and Liam Cunningham.

Young voices opposing repeal have featured too.

Katie Ascough, a UCD student, helped spearhead a secular campaign utilising the hashtag #OurFuture. One of the anti-abortion campaigns uses the simple slogan “Love Both”.

Sociologist Ethel Crowley, a specialist on rural Ireland, believes repeal will win – thanks to the young.

“I think age is a bigger factor than where you live, with older folks finding it more difficult to escape the clutches of Catholic thinking,” she said.

Abortion bans around the world

Total ban

Predominantly Catholic Malta is the only European Union country to totally ban abortion, imposing jail terms of between 18 months and three years if the law is broken.

Abortion is also banned in Andorra, the Vatican and San Marino, which are in Europe but not the EU.

Globally there are total bans in Congo-Brazzaville, Democratic Republic of Congo, Dominican Republic, Egypt, El Salvador, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Honduras, Laos, Madagascar, Mauritania, Nicaragua, Philippines, Palau, Senegal and Suriname.

In El Salvador the internationally criticised criminalisation of those found to have terminated pregnancies has led to women being jailed, some serving terms of up to 30 years.

Restricted

Many countries allow abortions in cases where the mother’s life is deemed to be in danger.

A partial list includes: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Guatemala, Iraq, Ivory Coast, Lebanon, Myanmar, Oman, Paraguay, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria, Uganda, Venezuela, West Bank/Gaza and Yemen.

Last September Chile ended its strict ban, which had been in force for decades, when then president Michelle Bachelet signed into law legislation to decriminalise abortion in certain cases, including on health issues.

In Brazil a bill is under consideration in congress that would ban access to all abortions, even in cases of rape and for women whose lives are in danger.

Unlike the rest of the United Kingdom, abortion is also illegal in the province of Northern Ireland except when the mother’s life is in danger.

The British government said in June 2017 it will fund abortions in England for women arriving from Northern Ireland.

Other countries also allow abortions only in cases of rape or threat to the mother’s or baby’s health.

In EU member Poland, which has one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the bloc, a new bill, which could pass in parliament where conservatives have a majority, would outlaw abortion except in cases where the mother has been raped or is a victim of incest.

In the United States abortion was legalised nationwide in 1973, but has been under pressure since Donald Trump became president, with some Republicans seeking restrictions.

The US state of Iowa in early May signed into law a ban on abortions once a fetal heartbeat is detected, which occurs as early as six weeks into a pregnancy. The Midwestern state now has the strictest legislation on abortion in the US.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)