The penny drops: ancient theatre’s legendary acoustics are just another Greek myth

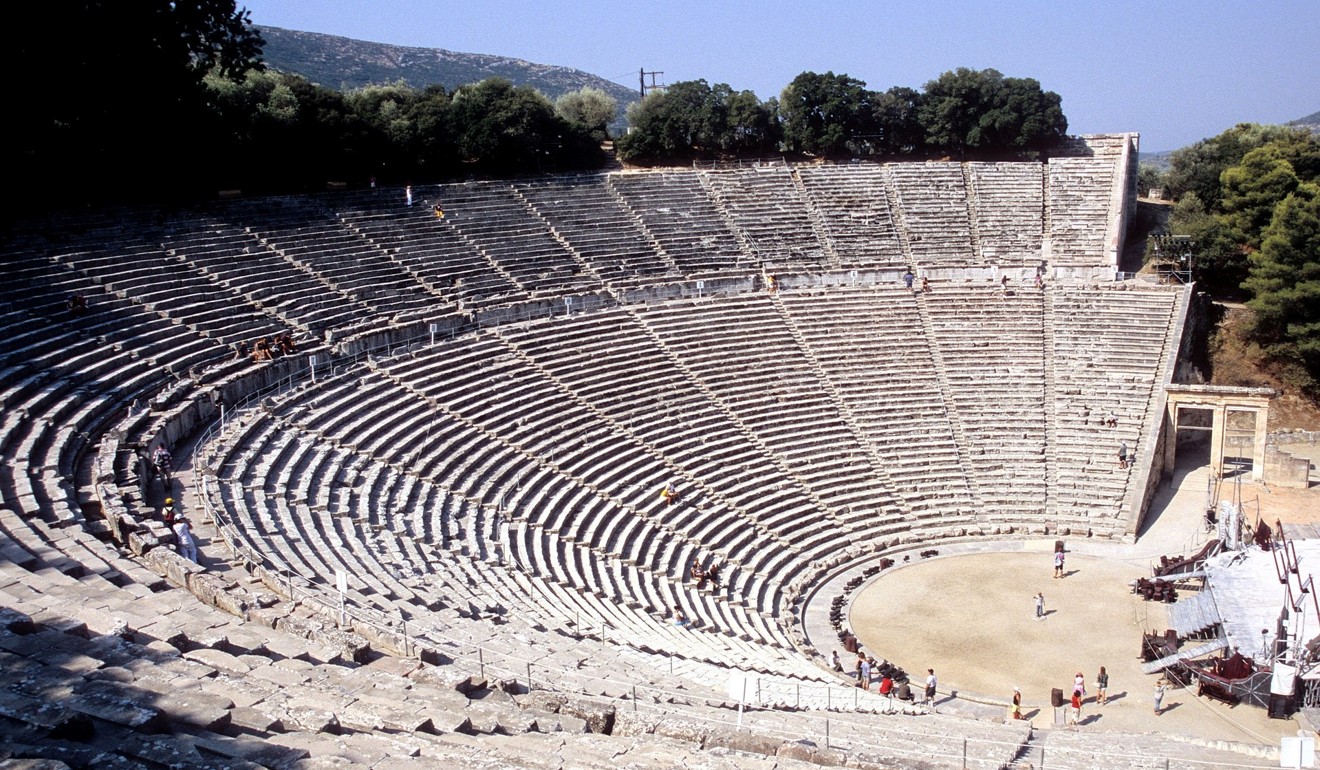

Scientists disprove the reputation of the 2,400-year-old Epidaurus theatre, where audiences in distant seats are said to be able to distinguish the sound of a coin falling or performers speaking in whispers on centre stage

It has been held up as a stunning example of ancient Greek sound engineering, but researchers say the acoustics of the theatre at Epidaurus are not as dazzling as they have been hailed.

Dating from the fourth century BC, and seating up to 14,000 spectators, the theatre has long been admired for its sound quality, with claims that audiences are able to hear a pin or a coin drop, or a match being struck, at any seat in the house. Even the British archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler raved about the theatre, declaring in clipped tones in a 1958 broadcast: “Even a stage whisper could be picked up by the furthest spectator with the cheapest ticket.”

But new research suggests such assertions are little more than Greek myth.

We kind of revert back to that idea that they had this wonderful knowledge and they were somehow in touch with something magical that allowed them to do it in that way

In a series of conference papers, which also involved experiments at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus and the theatre of Argos, Hak and colleagues describe how they tested the claims. They used 20 microphones, placing each one at 12 different locations around the theatre of Epidaurus, together with two loudspeakers, one at the centre of the “stage” – or orchestra – and one to the side. Both speakers played, with a slight delay between them, a sound that swept from low to high frequency, with the speakers in five different orientations. In total, they made approximately 2,400 recordings.

The team then used the data to calculate sound strength at different points in the theatre.

They then made a series of laboratory recordings of sounds, including a coin being dropped, paper tearing and a person whispering, and played them to participants, who adjusted the loudness of the sounds until they could hear them over background noise. The results were then fed into the team’s calculations to reveal how far from the orchestra the different sounds would be heard.

While the sound of a coin being dropped or paper being torn would be noticeable across the whole theatre, it could only recognisably be heard as a coin or paper halfway up the seating. For a match striking, the situation was worse, while a whisper would only be intelligible to those in the front seats.

Dr Bruno Fazenda of the Acoustics Research Centre at the University of Salford, who has carried out work on the acoustics of Stonehenge, welcomed the study, saying that it finally busted a myth – with the results tallying with his own experience of visiting Epidaurus.

“You can certainly hear things, but [the results] are right: if you want to have good speech intelligibility, good perception right up the last rows, then you need someone who can project the voice,” he said, adding that Greek thespians would have been expert at doing just that – possibly aided by the use of masks.

Fazenda believes the reverence for the theatre’s acoustics come, at least in part, from a popular belief that our ancestors had knowledge that has since been lost in time. “When we then come across these beautiful structures from the Greek and Roman eras, which were basically the very first clear acoustic design spaces, we kind of revert back to that idea that they had this wonderful knowledge and they were somehow in touch with something magical that allowed them to do it in that way,” he said.

Armand D’Angour, an associate professor of classics at the University of Oxford, said that, while the research reveals the state of the acoustics now, it does not necessarily shed light on the past.

“The research is based on theatre that has changed over the centuries, so it looks terribly precise and mathematical but in the end, we cannot be at all confident that the way it sounds today exactly replicates the way it would have sounded then,” he said, adding that research has suggested that the Greeks might have used all manner of devices to amplify sound, including placing hollow vessels at strategic locations.

Damian Murphy, professor of sound and music computing at the University of York, said that, while the research was probably the most detailed yet into acoustics of such sites, it was hard for modern minds to understand quite what the experience would have been like for ancient theatregoers.

“Any performing arts venue – it is not just about what they sound like, it is about the experience of going there,” he said.