When dinosaurs became birds: studies of prehistoric Chinese fossils paint a picture of transition moment in evolutionary change

- The birds, called Jeholornis, were some of the first animals to diverge away from dinosaurs and become birds

- Scientists found the birds could have been fruit eaters with a strong sense of smell that were most active during daytime

It is common knowledge that birds are the evolutionary descendants of dinosaurs, with one of the more interesting moments in prehistoric biology being the years when the two crossed over and lived side-by-side.

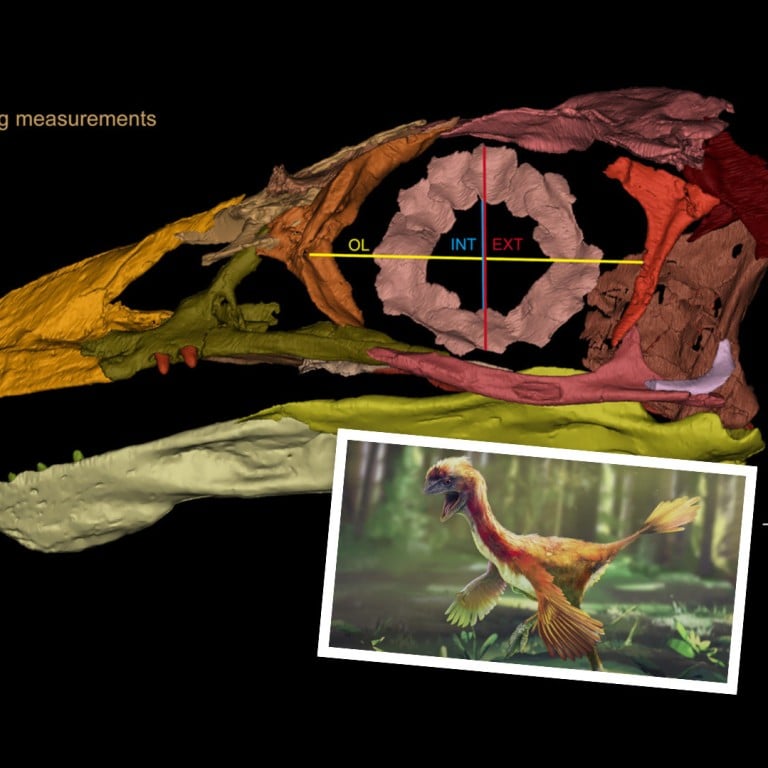

They discovered that the bird likely had a far more robust sense of smell than modern birds. They believe this is due to larger olfactory bulbs in the reconstructed skull, which are a part of our brain that receives neural inputs from our sense of smell.

Hu Han, the study’s lead author from the department of earth sciences at the University of Oxford, told the South China Morning Post: “We could not determine if this [sense of smell] is a key feature during hunting or mating. It is very difficult to predict this kind of relationship between one or some characteristics in fossils, especially considering that fossil birds are even rarer than other fossil animals.”

The study also found that the bird was probably most active during the day, based on analysis of its eyes, which were different from famously nocturnal birds like owls.

This brain reconstruction is particularly interesting when integrated with the team’s other study published in August that found Jeholornis may have exhibited the first example of prehistoric birds eating fruits.

“Considering that birds are important fruit consumers today, and play important roles in seed dispersal, these discoveries indicate that birds may have been recruited for seed dispersal during their earliest evolutionary stages,” said Hu.

Hu said that fruit dispersion was particularly important on a macro scale because there was a “terrestrial revolution” during the Cambrian period which started around 125 million years ago, when flowering plants began to spread worldwide.

Today, birds are a crucial player in the reproduction cycle of flowering plants, so to see evidence that birds helped flowering plants spread hundreds of millions of years ago could “therefore explain, at least in part, the subsequent evolutionary expansion of fruits”, the team wrote in their report.

Jeholornis is a wonderful bird, offering a window into a world where dinosaurs and birds lived side-by-side.

“The transition period looked so amazing,” said Hu. “You could see flying, or more correctly, gliding, feathered bird-looking dinosaurs like the Microraptor as well as toothed, clawed, dinosaur-looking birds - like Jeholornis.”