Lost to China for decades, ancient classics get a new lease on life through artificial intelligence

- Many Chinese classic works were lost or destroyed during the turmoil of the 19th and 20th centuries

- However, many are being rediscovered in overseas collections and returning to China

When Cao Tingdong, a poet in the Qing dynasty (1636-1912), wrote The Surviving Poems by 100 Song dynasty Poets, he had no idea it would end up travelling halfway across the globe.

The poet, born in 1700, loved poetry when he was young and was keen on taking government exams, competing for a spot in the imperial court, according to his autobiography. After failing several times, in midlife, he went into seclusion in the mountains and wrote books explaining previous classics, as well as collected works of other poets.

He spent his last years in peace, but his book did not suffer the same fate.

It was stored in an imperial Qing dynasty library. But when riots broke out in the mid-1800s, the book was lost.

For the following century, nobody knew its exact whereabouts after this. It was stored with a private collector at one point, then lost again. And now, it rests in the library of the University of California, Berkeley, most likely purchased through its acquisition programmes in the first half of the 20th century.

In May, the book finally made its journey home to China, in the form of a digitised copy.

It was among the first batch of works to be completely digitised and uploaded to a searchable website, in a new project spearheaded by Sichuan University, Berkeley and the Alibaba Group, the owner of the South China Morning Post.

The idea is that the ancient classical texts can be better preserved and will actually be read and used by the public.

Exposed to the light of day

In China’s modern history, many precious classical texts were lost overseas during wars and turmoil, but many of these were preserved in research libraries and museums around the world.

There have been some efforts to protect and digitise existing ancient texts, including a database launched by the Chinese government State Council in 2007, that has more than 3 million ancient books across 13 provinces on record.

In 2016, a digital library was launched by the National Library of China, with more than 33,000 books. But like most projects concerning ancient books, the text was difficult to digitise, and the digital library has scanned pages of these books.

In 2018, Alibaba’s Academy for Discovery, Adventure, Momentum and Outlook (DAMO) reached out to the Sichuan University and found Wang Guo, deputy dean of the School of History and Culture and Chen Li, veteran librarian at the school.

Chen then reached out to Peter Zhou, director of the C.V. Starr East Asian Library at Berkeley, who had visited Sichuan University in 1998.

It was an instant match. Zhou told the Post he felt the proposal was in line with Berkeley’s open access initiative.

“It is our position that research libraries should make copyright-free materials openly available for scholars and public users to benefit research and scholarly communication,” he said.

Chen declined to provide a comment to the Post.

Currently, research libraries in the US promote open access for historical materials, including rare books and manuscripts that are out of copyright, through digitisation and publicly accessible platforms, Zhou said. He hopes Chinese research libraries will do the same.

He handpicked some of Berkeley’s most valuable ancient books and manuscripts to provide to the project team, some of which were the only copies in the world.

This included texts that dated back to the Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties, such as the Jinsushan Tripitaka, which represent some of the earliest imprints from China, Zhou said.

“In addition, holdings from some of the respected collectors and private libraries in the history of China are also considered extremely valuable, such as the Tianyi Chamber,” he said. “The Complete Library in Four Sections is from one of the most important imperial libraries, the Imperial Wenlan Library. This copy carries Emperor Qianlong’s seal.”

The team decided to call this project “Handian Chongguang”, meaning “To expose Chinese classics to the light again”.

Teaching AI ancient Chinese texts

Early this year, Berkeley mailed a hard drive to DAMO.

It contained a sea of digital folders, each corresponding to one book, said Xu Yinghui, head of DAMO’s Vision Lab. Each page of the book is scanned into one picture file — 200,000 pages, 200,000 files.

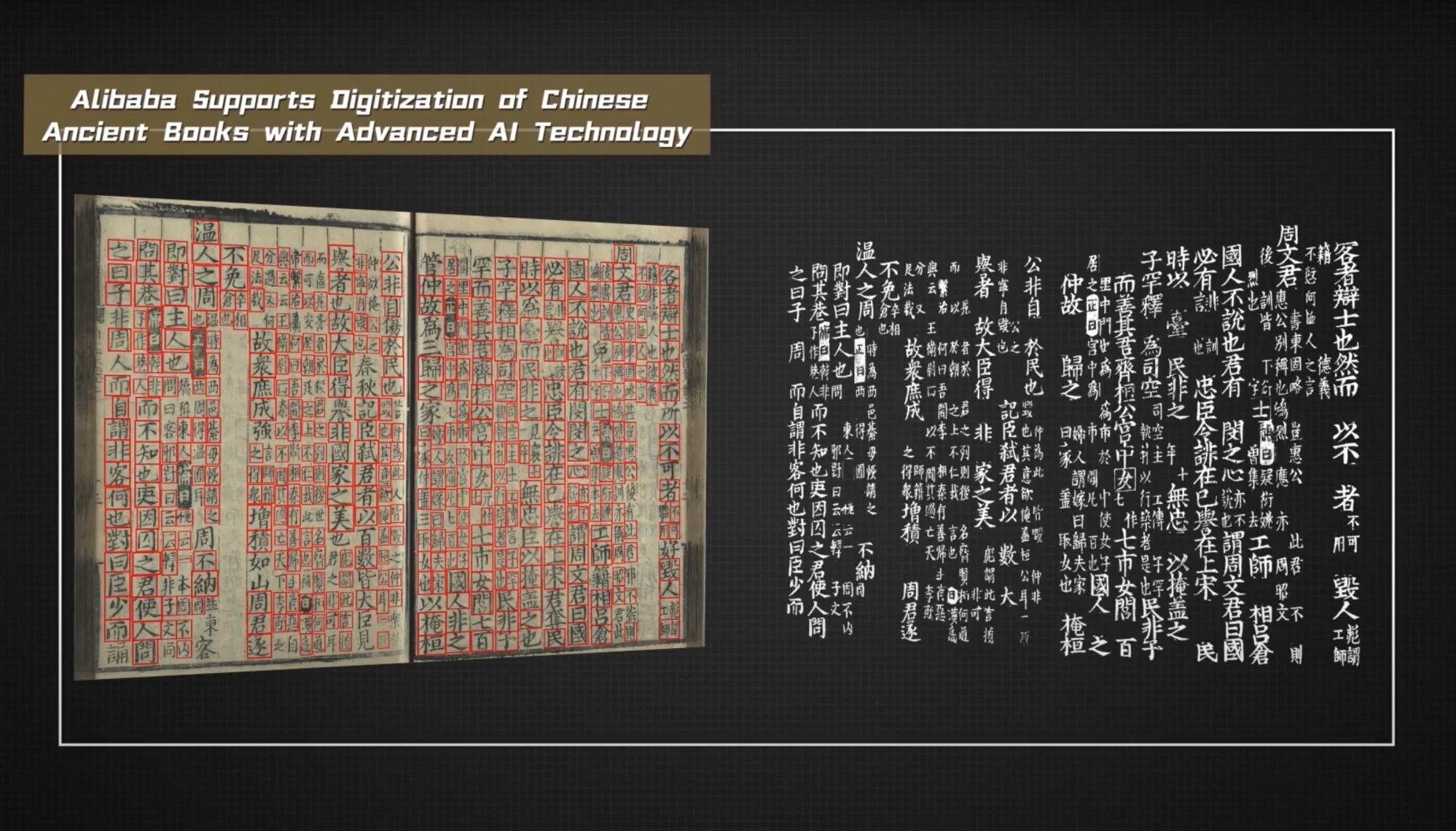

The general technique is called optical character recognition (OCR), where the machine converts images of text into text that can be edited, whether from a scanned document or a photo of a document, Xu said.

In modern day, OCR is commonly used in all languages to convert printed paper documents into machine-readable text documents. But there was one issue for this particular project: there wasn’t a matching database for ancient Chinese characters, most of which aren’t included in today’s speech. The team had to build one from scratch.

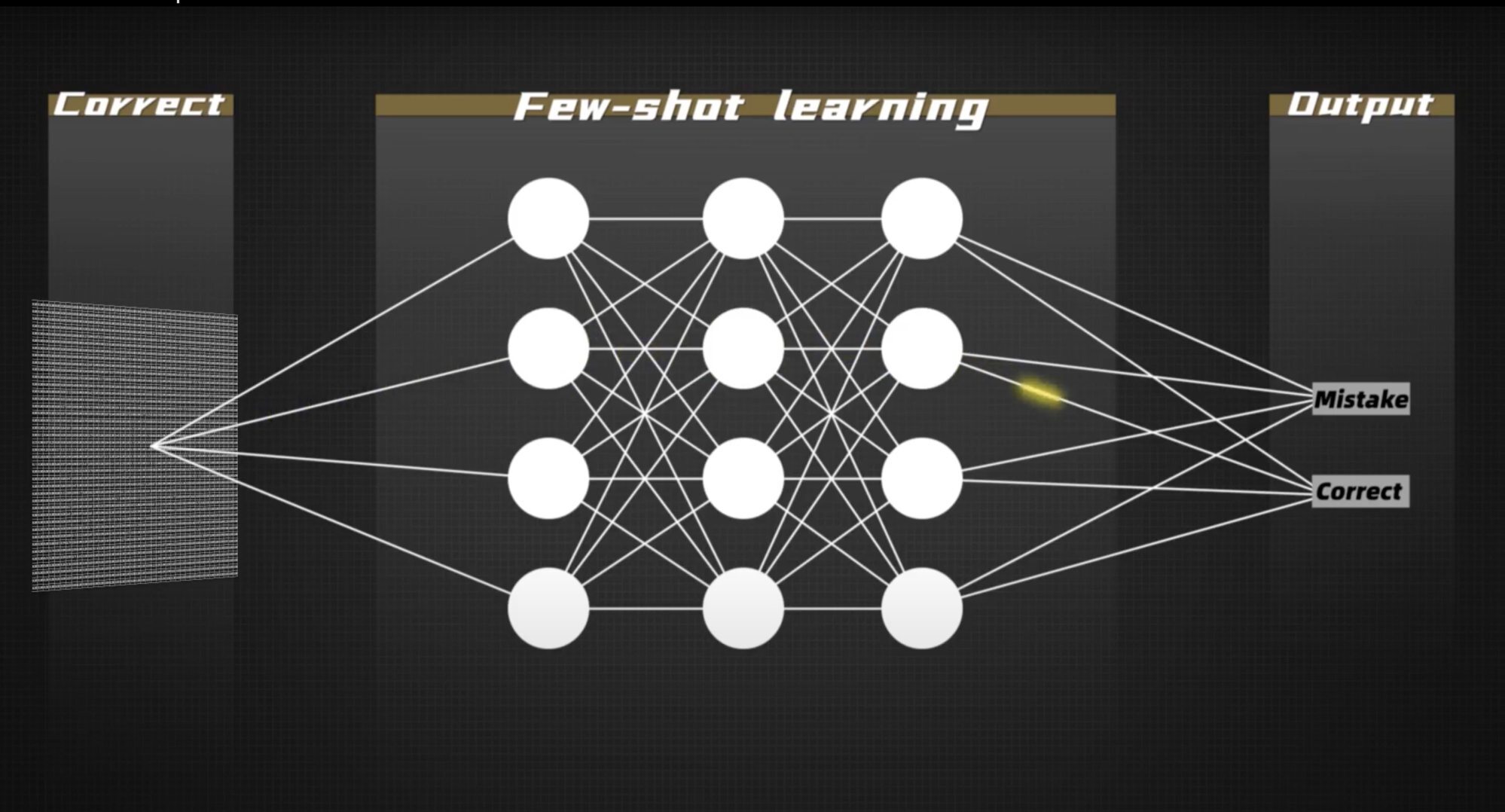

In order to eliminate the amount of work, the team used AI to scan all the characters in a book and group similar-looking ones together. Next, a team of classics experts steps in to mark what words the clustered groups are.

“This way, what originally were 100,000 words becomes 3,000,” Xu said.

But there were still challenges. Ancient Chinese texts, which began as hieroglyphs, evolved over the years. Sometimes what AI recognised as different characters were actually the same character written in different styles, or during different time periods.

To keep confusion to a minimum, Xu kept AI focused on one book at a time, as the style is generally consistent within one book. As for different forms of one word, he copes by creating a sub-category that associates them with one word.

The end result was a system that has 97.5 per cent accuracy rate, and a website that enables search. The rate, even though still short of the 99.98 per cent required of publications by law, is a starting point.

Where to next?

Currently, when one logs on to the Handian Chongguang website, they would find all the photographed pages lined up at the bottom of the web. On the top, there is a search box, where people can enter keywords and find out on what page and books these words appeared.

During the website launch ceremony last month, Zhang Jianfeng, the director of DAMO, said the entire AI system and platform will be handed over to an authoritative public organisation for long-term operation. Currently, DAMO is still in discussion over who will run the platform.

By opening up the system to the public, Xu hopes it will become smarter. When the public uploads their own classical texts into the system, a team of experts will help mark the words for the database.

“It’s like an active learning process,” he said. “As more and more input comes into the system, our experts will interfere less and less.”

.jpg?itok=H5_PTCSf&v=1700020945)