Hired by Japanese toy giant Bandai to create a manga series for Digimon, Hong Kong artist is now out of luck, love and money

- Yu Yuen-wong hit the jackpot in the late 1990s but life has been rough since the local industry imploded

Cartoonist Yu Yuen-wong was at the height of his powers in 2005 when he made enough money to buy his own flat – a 700 sq ft home in Tseung Kwan O worth HK$2 million (US$255,000). It was meant to be a love nest for him and his then girlfriend, whom he planned to marry.

Little did he know that in four years his dreams would come crashing down after an industry slump.

“My life is like a manga story about adventure, [and] in the beginning I was very lucky,” says Yu, now in his 40s.

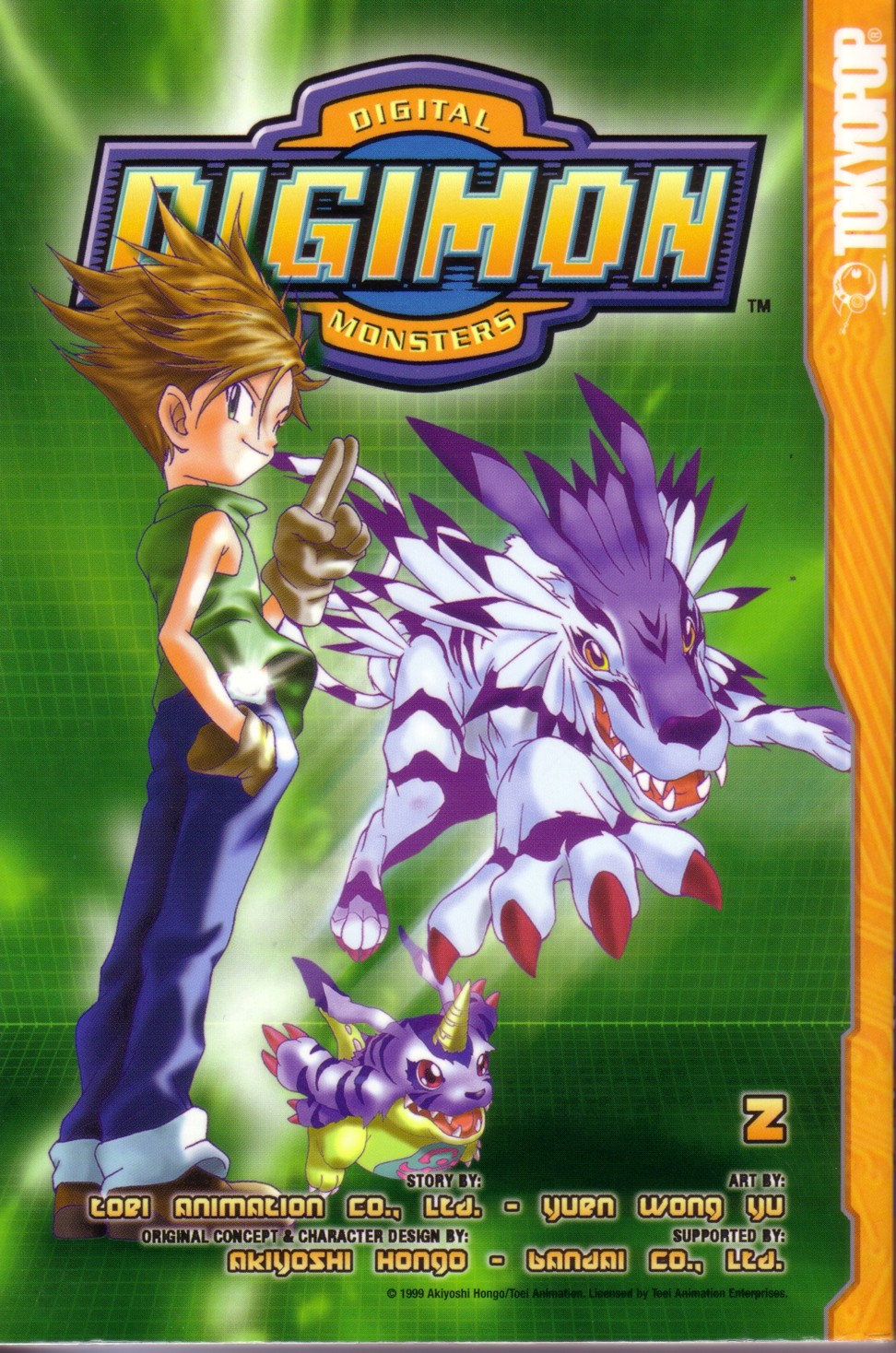

His good fortune began in 1999, when Japanese toy giant Bandai hired him to create a manga series for Digimon, one of the brand’s successful anime franchises about mini-monsters.

He published 20 Digimon books, some of which were sold in 28 countries and regions including Taiwan, Thailand and Malaysia. Yu could earn up to HK$60,000 (US$7,650) in royalties for each title, while also receiving HK$20,000 monthly from magazines that serialised his work.

“I was 20, just in ecstasy when I got the job. It was my first opportunity to create my own manga,” says Yu, who was then an assistant cartoonist for a local publisher.

Yu was selected to work on the series’ Hong Kong edition, and he found pleasure in blending local elements with the beastlike Japanese characters.

“My [human] protagonists are ordinary Hong Kong teens, buying fish balls at convenience stores after school. The stories were often set in Kowloon City and streets full of neon lights,” he recalls.

Hand-carved mahjong tiles live on in Hong Kong

“I grew up reading Japanese comics, and admiring the rigorous work ethic of Japanese artists. But I thought I could do better in portraying characters, like enriching their facial expressions and monologues,” Yu says, thinking back to those days where he would work 10 hours daily on his craft.

“I didn’t want to embarrass Hong Kong. So for me there’s always comparison and I felt this pressure to improve myself all the time.”

Still, Yu says he did not expect the Digimon comics to become such a hit, attracting fans from Japan to visit his office and creating opportunities to hold book signings. Even buying a flat, he says, was “a decision that came so naturally”.

He remembers feeling like he was “floating on air”, exchanging dreams with peers about how they intended to get famous and have their work adapted into animations and games. “Back then everything seemed possible.”

Li Wai-kin, 40, a former cartoonist who has known Yu for more than 20 years, shares this sentiment, describing his years of drawing manga as exhausting but “the happiest period in life”.

But at the turn of the century, the local comics scene declined, with the rise of digital mobile devices. According to Yu, a major manga magazine could still sell hundreds of thousands of copies per week in the 1990s, while the number has plunged to several thousands.

Yu Yi, owner of local publisher Creation Cabin, says this decline also stemmed from a lack of diversity in topics, with stories about martial arts and street fights dominating Hong Kong manga for decades.

Hong Kong comics peaked from 1970 to 1980, but by the time we entered the industry its glory was pretty much gone

“Reading local comics is somehow an old-fashioned thing for teens now; our readers are ageing and decreasing,” he says.

In Japan, however, the anime industry has a system that constantly spawns new genres, with a prevailing belief in society that “animation is for everyone”, according to Yu Yi. Having worked as a story planner in several publishers for about 20 years, he says Hongkongers hold negative attitudes towards manga, thinking it only for young people.

“Hong Kong comics peaked from 1970 to 1980, but by the time we entered the industry its glory was pretty much gone,” says Li, who became an actor in 2009 after trying his hand as an artist for six years.

Yu Yuen-wong, on the other hand, decided to stay in the profession and tough it out.

After finishing Digimon in 2006, he lived without stable income for more than a year, earning a mere HK$2,000 a month. Surviving on this and savings from the Bandai windfall, he realised by 2008 he could no longer afford the mortgage for his new flat.

Five female manga artists who’ll continue legacy of late Momoko Sakura

He had not moved into it since the purchase in 2005 and had been living with his parents while renting out the property. Losing the flat, recalls Yu, was the turning point of his relationship with his then girlfriend.

“Suddenly all the money was gone and it triggered so many fights between us. In the end it just didn’t work out,” he says.

“When I handed the key to the buyer, I felt upset but also relieved, as the burden was finally off my shoulders.”

Yu now mainly creates illustrations for local novelists, hoping to publish another comic book of his own if he gets together enough money one day.

“Fate likes to tease people,” he says. “There are just a lot things I can’t control.”