Hong Kong’s national security law: 3 years on, more than 160 prosecutions, 8 bounties later, what else can the city expect?

- Most arrests still linked to 2019 social unrest, so law will be used less frequently after this phase, sources say

- Jimmy Lai’s trial and handling of 47 opposition activists will be closely watched on how law is shaping out

“Rats in the streets”, “turtles with heads in shells” and “eaters of human-flesh buns” – these are among choice descriptions Hong Kong officials have thrown at a group of eight activists now operating overseas.

The announcement was followed by multiple arrests of local activists accused of raising funds to support the overseas community. Both events pushed Hong Kong back into the international limelight in the past week, overshadowing the government’s ongoing global campaign to attract tourists and talent.

Western politicians launched more attacks on the city’s leadership as they voiced concerns over the law’s long-arm jurisdiction, while Beijing officials accused them of sheltering fugitives.

Analysts say the latest actions reflect a new focus of the law’s application as the Beijing-imposed national security law passed its three-year-mark: targeting the growing community of dissidents overseas and their affiliates at home.

A Post analysis of the 265 related arrests over the past three years also points to a shifting pattern of police targets – from accusing big names of crimes stipulated in the national security law in the first two years, to going after suspects using a colonial-era sedition law in the past year.

The roughly 30 arrests made in the past 12 months for alleged national security offences is also less than the number of people detained over them since 2020.

A senior government source said the authorities hoped “in one or two years”, once existing prosecutions were settled, there would not be “too many cases”.

8 Hong Kong wanted activists should be treated like ‘rats in the street’: John Lee

So far, all cases brought before the courts have involved non-jury trials, as provided for in the law, and the conviction rate has been 100 per cent.

In the coming year, the application of the legislation is likely to be shaped by several high-profile trials and the move to have a local version of the national security law.

Analysts say one factor outside the ambit of the law will be how tensions between the world’s two superpowers evolve, and that a no-compromise, hardline approach on national security will prevail if the United States continues to try to contain China.

‘Kill the chicken to scare the monkeys’

Last week’s announcement of sizeable bounties targeting the eight vocal dissidents caught some in the diplomatic community by surprise. And this was despite the fact that at least dozens of individuals have been on the national security police’s wanted list since the law took effect.

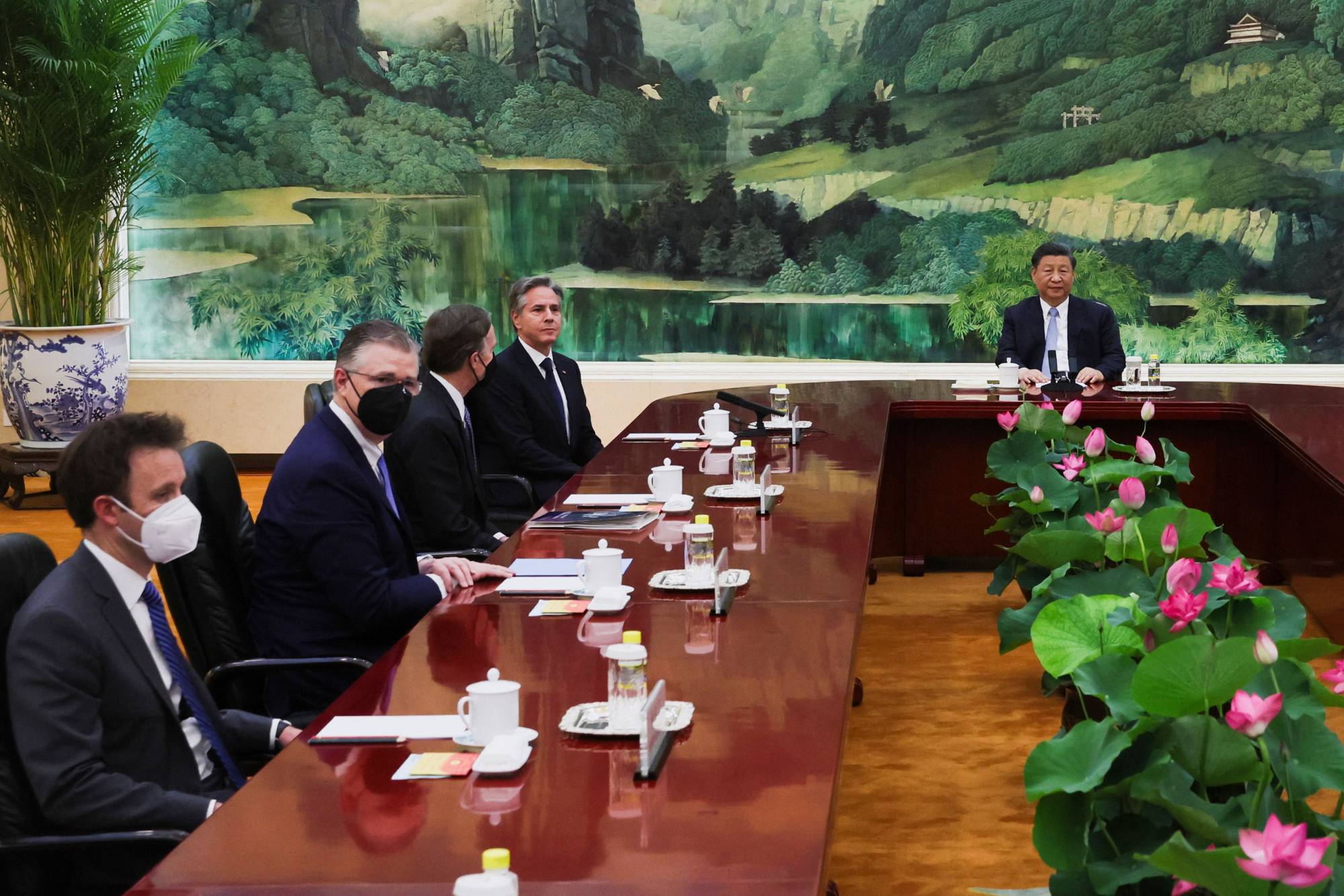

It came just weeks after US Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Beijing, where he agreed on the need to “stabilise” the bilateral relationship, and three days after Washington moderated its travel advisory for Hong Kong to the second-lowest level on a four-point scale.

In announcing the cash rewards of HK$1 million (US$127,750) for information leading to each arrest of the eight – an amount higher than what authorities had previously set for murderers and rapists – national security police provided mugshots of the eight fugitives and explained their alleged wrongdoings one by one at a press conference last Monday.

The eight are former lawmakers, advocates and a union representative: Nathan Law Kwun-chung, Elmer Yuen Gong-yi, Dennis Kwok, Kevin Yam Kin-fung, Anna Kwok Fung-yee, Mung Siu-tat, Finn Lau Cho-dik and Ted Hui Chi-fung.

Most were accused of “seriously endangering national security” by calling for independence, urging foreign countries to sanction Hong Kong judges and proposing ways to undermine Hong Kong’s status as an international financial centre, according to Chief Superintendent Steve Li Kwai-wah.

The high-profile action was a classic case of “killing a chicken to scare the monkeys”, political analyst Lau Siu-kai told the Post, referring to an old Chinese proverb which means to intimidate a big adversary by destroying a small one.

He believed that authorities decided to act after noticing a growing network of overseas “underground activities” involving crowdfunding led by the dissidents.

“Different sorts of soft confrontation persist, some under the coaxing of external forces to smear Hong Kong and instigate malicious actions,” said Lau, a consultant with the semi-official Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies.

“[The bounties] served as a stern global warning not to support [the overseas activists’] in any form, including financial support.”

Hong Kong’s leader condemns US pressure on judges, warns of persistent threats

Michael Davis, formerly of the University of Hong Kong (HKU)’s law school, said he believed that authorities hoped to stop the activists from “shining a light on developments in Hong Kong at a time when they are trying to uplift the city’s image”.

But Davis, now a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Centre in Washington, questioned the tactic, saying it would only help them gain more attention and likely grow their support base.

The eight accused remained defiant and vocal, with Yam, a lawyer, tweeting that he had been “flooded with congratulations” for receiving the “honour to be on the list”.

Former opposition lawmaker Law, who was among the first to flee for the United Kingdom after the national security law was introduced, obtained refugee status two years ago. His Twitter followers have risen rapidly, hitting 333,500 at last count. One of his initial tweets denying collusion charges was viewed by 625,600 people.

Who are the 8 Hongkongers wanted over national security with HK$1 million bounties?

The fresh round of arrests by the national security police last week was in connection with alleged fundraising activities in support of Law, police insiders said.

The five suspects, affiliated with the now-defunct political party Demosisto, were accused of conspiring to collude with a foreign country or external forces and to commit acts with seditious intent.

One of the arrested, Li Kai-ching, is the director of a company that runs an app called Mee, which listed so-called yellow businesses sympathetic to the 2019 protests. Last week, the app went dark and its social media accounts vanished.

Long-arm jurisdiction not unique but untested

The national security law’s extraterritorial application has been a bone of contention. Articles 37 and 38 of the law state it applies to residents and non-residents alike and covers offences committed outside the city.

The fugitives are last known to be in the United States, the UK, Australia and Canada, which have suspended their extradition treaties with Hong Kong due to the security law and criticised its extraterritorial application.

US State Department spokesman Matthew Miller criticised the law’s long-arm jurisdiction for setting “a dangerous precedent that threatens the human rights and fundamental freedoms of people all over the world”. UK Foreign Minister James Cleverly said the arrest warrants were a “further example of the authoritarian reach of China’s extraterritorial law”.

But Professor Albert Chen Hung-yee, a legal scholar at HKU and a former member of the Basic Law Committee, argued it was not unusual for a law covering serious criminal offences to have territorial application.

“The US is also well known for its application of extraterritorial laws,” he said.

US extraterritorial legal instruments cover wide-ranging areas, from anti-corruption to anti-terrorism and from economic sanctions to the collection of personal data.

Earlier in February, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs published a report criticising the US expansion of its long-arm jurisdiction as a tool to “advance hegemonic diplomacy and pursue economic interests” that blatantly meddled in others’ internal affairs.

It named the Sanctions Act, National Defence Authorisation Act and Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) as examples, among others.

Do whistle-blowers like Edward Snowden still have a place in Hong Kong?

Earlier this week, Hong Kong former home affairs minister Patrick Ho Chi-ping, who was convicted in the US for paying bribes to the presidents of Chad and Uganda in a United Nations-linked conspiracy, criticised the extraterritorial application of American laws.

In an article titled “Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA): United States’ another long arm” published in a mainland Chinese media outlet, he described the law as a “naked manifestation of American hegemony and exceptionalism” to maximise its economic gains and suppress competitors of US corporations.

The Beijing-decreed security law’s long-arm application is yet to be tested in Hong Kong’s courts.

A case to watch involves a 23-year-old Hong Kong female student living in Japan who was arrested in April for posting “pro-independence statements” on Facebook. She became the first person arrested for such actions outside the city.

Yuen Ching-ting was not charged with any of the four offences in the security law, but with sedition instead. Her defence lawyer challenged the use of the legislation in court, arguing it did not contain a provision conferring extraterritorial jurisdiction.

Hong Kong woman, 23, to face sedition charge over Facebook posts

The use of the sedition law, rather than the national security legislation, has become common in the city’s handling of security-related crimes. Sedition charges were slapped on the bulk of the 30 or so arrests made by national security police in the past year. Only four of the cases were charged for crimes spelled out in the law: secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces.

National security police have so far arrested 265 people aged 15 to 90 since the law came into force on June 30, 2020. The force said 161 people and five companies had been charged. A total of 79 have been convicted.

A Post analysis of the cases found the government has won every case and the vast majority of procedural decisions.

Nearly four in five of those charged with national security offences have been denied bail, and some have spent more than two years in detention awaiting trial.

Thomas Kellogg, an American legal scholar who researches national security cases in Hong Kong, said the trend reflected a changing phase of the law’s application – from reshaping Hong Kong’s political and legal institutions in the first two years to a consolidation phase of maintaining the new status quo in the past year.

Offenders convicted of sedition can be punished by a fine of up to HK$5,000 and two years in prison for their first offence. Under the national security law, those convicted can face life imprisonment.

“The security law and sedition are most often used to punish the exercise of basic rights, including free speech, free expression and free association – most of the cases brought thus far would not be considered crimes in other, rights-respecting jurisdiction,” Kellogg, the executive director of the Centre for Asian Law at Georgetown University in the US, said.

“This trend shows that Hong Kong’s legal system continues to diverge from its Basic Law roots – the Basic Law human rights provisions simply have not played a role in national security cases thus far.”

Hong Kong woman arrested, 23 detained near park that once hosted June 4 vigil

HKU’s Albert Chen said the sedition law “covers a much broader range of speech” than the national security law itself.

“We have yet to see how the higher courts in Hong Kong interpret and delineate the scope of this offence taking into account human rights laws,” he said.

But he said so far the number of ordinary people affected by the national security law “can be regarded as relatively small”. He noted about 100 individuals had been prosecuted for national security offences, if the 47 pro-democracy activists and some other high-profile arrestees were excluded.

Chen also did not see Hong Kong’s common law system deteriorating after the security law took effect in the city.

The law had been effective so far in “preventing” crimes, he said, citing the reason China’s top legislature, the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, gave a month before the law took effect.

The law came into existence to deal decisively with the proliferation of calls for Hong Kong independence and attempts to create chaos, the government has said repeatedly, allegations mostly tied to the 2019 anti-government protests.

Senior Counsel Ronny Tong Ka-wah, an executive councillor, said he expected the number of arrests in connection with the four crimes of the security law would “significantly drop”.

“Most provisions of the national security law targeted deeds or speeches in the 2019 protests. Future arrest numbers will drop significantly as the existing cases already served as a deterrent effect in society,” he said.

A government source said the administration would unlikely use the law readily in future, even as it now had it handy in its legal toolbox. “If we maintain order, there is unlikely to be a need to use the law frequently and we have been restrained,” he said.

‘Challenged books’ swept off Hong Kong library shelves, but what about shops?

US-China rivalry determines law’s application

Tong expected that during the legislative process, the Crimes Ordinance would also undergo “major amendments” to align with principles of Article 23 and the Beijing-imposed security law.

He expected chapters about treason and offences against the crown might be abolished and that the sedition law could be reformed to keep abreast with societal developments.

Hong Kong’s Article 23 ‘should define state secrets differently from mainland China’

The biggest national security trial involving the group of 47 opposition figures is also likely to proceed through the courts this year. Last month, three national security judges ruled that prosecutors had made a strong enough case against 16 of them who had pleaded not guilty to a charge of conspiring to commit subversion.

Some of those who pleaded guilty, including former lawmaker Au Nok-hin, testified against fellow opposition colleagues during the trial. The court heard Au citing legal scholar Benny Tai Yiu-ting, the architect of the unofficial primary, as saying that having majority control of the legislature was a “constitutional weapon of mass destruction”.

The long-awaited trial of Jimmy Lai is expected to start in September, after it was delayed because he sought to have a UK-based lawyer on his defence team. The Apple Daily newspaper founder faces charges of sedition and conspiracy to collude with foreign forces. He has spent all but eight days behind bars since December 3, 2020.

Hong Kong’s High Court rejects bid by Jimmy Lai to drop national security case

Political analyst Lau said the US-China rivalry could influence how hardline Hong Kong, as guided by Beijing officials, would be in handling national security cases, even as it would brook no interference on such matters.

“If Washington continues to contain, isolate Beijing and act hostile in shaping its so-called new world, Beijing has no choice but to firmly defend its core interests,” he said.