Hong Kong: an awkward partner in China’s 40-year quest to open up

- The city has been critical to the country’s efforts to embrace private commerce, but at times has also been an awkward partner

- ‘One country, two systems’ concept has been put to test, most recently by Occupy protests

Cooking oil, biscuits, peanuts, stockings and soap were the most popular gifts that travellers from Hong Kong took with them when they headed to mainland China back in 1979.

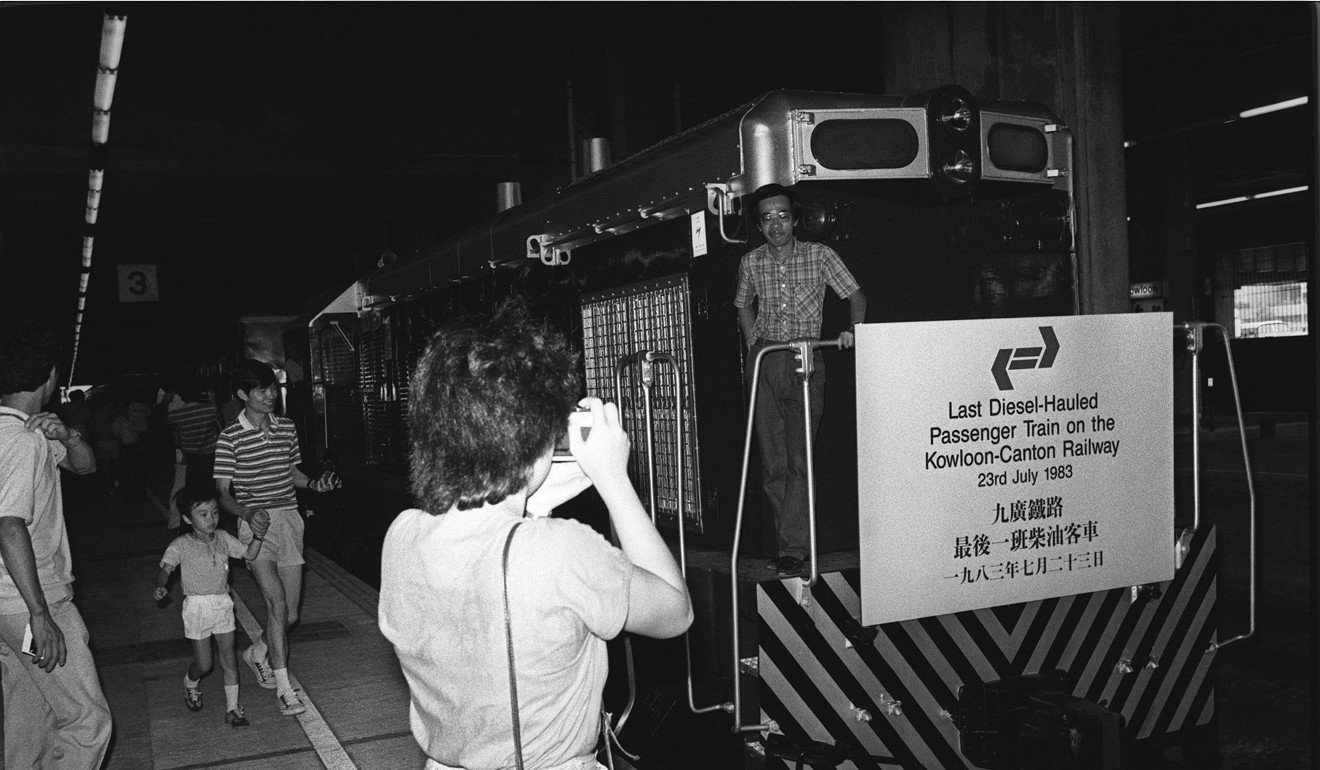

These items, rationed across the border at the time, were regularly found nestled in the suitcases of northbound passengers on the Kowloon-Canton Railway through train, according to press reports.

‘Irreplaceable’: Xi praises Hong Kong, urges integration with China’s plans

The rail service had resumed in April that year after 30 years, stalled since the communists took power in China.

The renewed link was a harbinger of Hong Kong’s return to the mainland under the “one country, two systems” model. It also proved to be a catalyst enabling the reform and opening up of China.

Forty years on, in early November this year, President Xi Jinping acknowledged the “unique and irreplaceable role” of Hong Kong in the country’s opening up when he met the city’s elite in Beijing.

Yet, among ordinary Hongkongers, a certain restlessness runs like an unruly thread in the ties that bind the city to the motherland. As in the past, the nature of closer integration, the fate of Hong Kong’s rights and freedoms, and the pace of political reform remain on the minds of those invested in the place’s future.

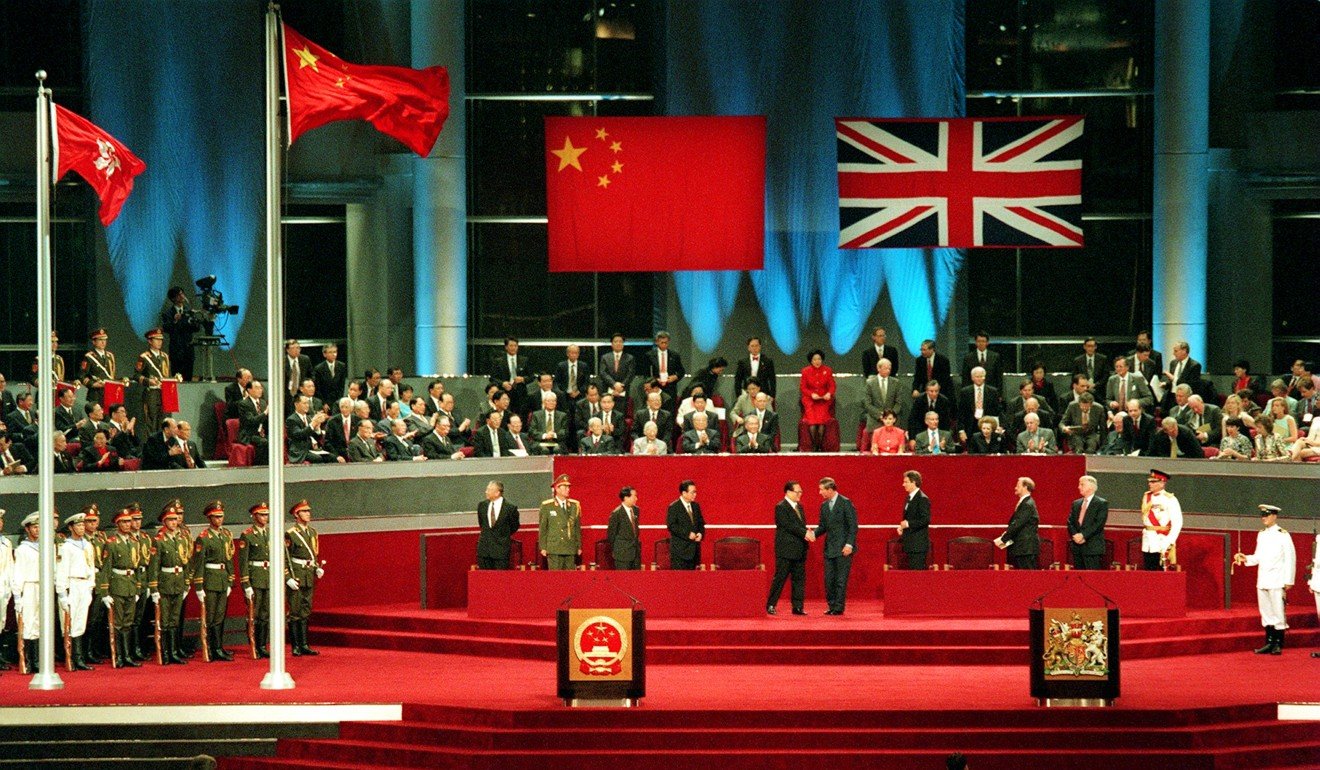

Over the past 40 years, reform and opening up and Hong Kong’s handover in 1997 were set in motion as two experiments running almost in parallel, often in confluence and sometimes in conflict.

Reforms, spittoons and Deng’s ‘double promise’

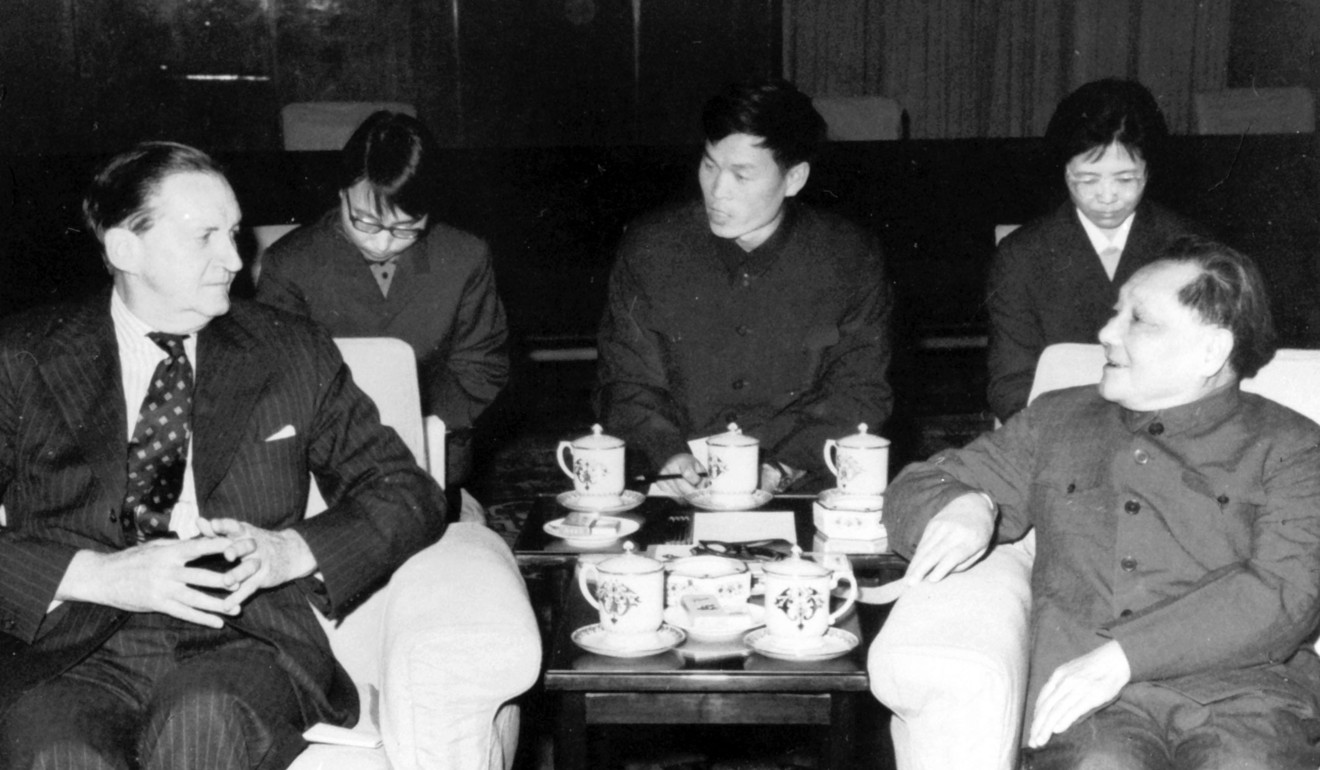

In March 1979, amid news of new leader Deng Xiaoping’s plans for economic reforms, then governor of British-held Hong Kong, Murray MacLehose, visited Guangzhou and Beijing. His purpose was ostensibly simple: to explore extending colonial rule beyond 1997, when one of two leases would run out.

Seven Hongkongers among contributors to China’s economic ‘miracle’, Xi says

His real agenda was to let China know not so subtly that having Hong Kong back in the fold of the mainland would ruin the city and derail China’s opening up.

Lau Siu-kai, vice-chairman of the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies, recalled: “The British business community was nervous. They thought the return to Chinese rule would be fatal to the economy, fatal to their businesses.”

The diminutive Deng, a survivor of the Cultural Revolution purged not once but twice, was not so easily deterred.

Where to now? 40 years after the big experiment that changed China

“In this century and for a long time in the next century, Hong Kong will continue to engage in its capitalism, while we engage with our socialism,” he told MacLehose coolly through interpreters.

That was the genesis of “one country, two systems”, a notion that commentators and documents suggest Deng had only in the broadest of strokes at the time, leaving the canvas to be filled out over the years of negotiations that followed.

Tam Yiu-chung, now Hong Kong’s sole delegate to the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, China’s top legislative body, said Deng was determined to have a “double win” – roll out massive reforms with no compromise of territorial integrity.

“Deng judged that China could have both: economic reforms and sovereignty. How? ‘One country, two systems’,” Tam said.

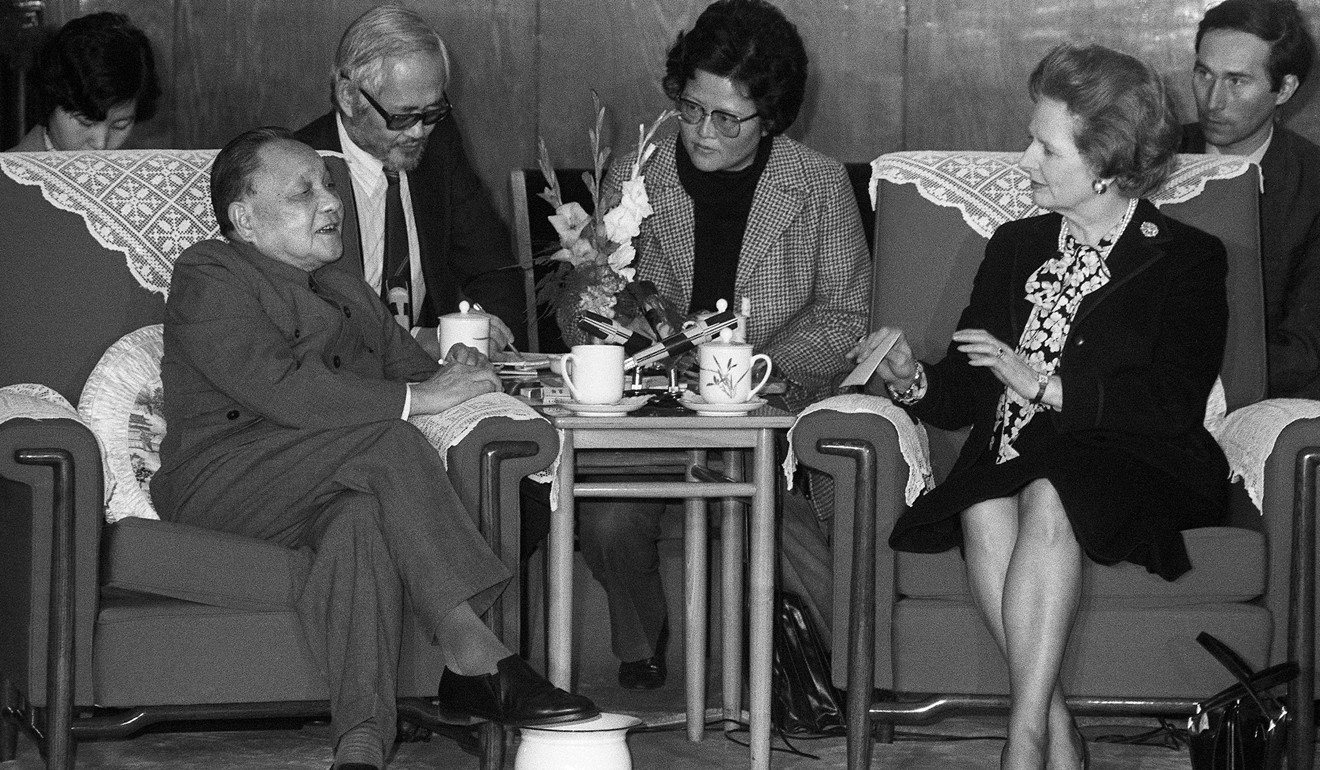

When then British prime minister Margaret Thatcher visited Beijing in September 1982, Deng rebuffed her request to retain Hong Kong. Ominously, injury was added to the insult – Thatcher fell while walking down stairs at the Great Hall of the People.

But Deng assured her of Beijing’s interest in Hong Kong’s success, saying: “The continuation of Hong Kong’s prosperity fundamentally depends on the implementation of policies suitable for the city.”

In June 1984, when Deng met a delegation of Hong Kong business and political leaders, he articulated how a prosperous Hong Kong would make vital contributions to China’s reform and opening up, and that the political innovation of “one country, two systems” might extend one day to Taiwan, a renegade province in Beijing’s eyes.

You are all good men. I have many bad habits. One is smoking, one is drinking. Also, I need a spittoon. Spitting contravenes the Western lifestyle most.

“We would allow some regions, such as Hong Kong and Taiwan, to practise capitalism as supplements to the socialist economy,” he said.

After the Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed in 1984 and the handover date set for 1997, next came the task of hammering out the city’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law.

It would set out that while Hong Kong would be an inalienable part of China, the special administrative region would enjoy “a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defence affairs”, and be “vested with executive, legislative and independent judicial power, including that of final adjudication”.

Despite these guarantees, doubts festered. The drafting committee’s heated discussions were a portent of divisions then and evident to this day.

There were concerns over whether freedom of speech would be jeopardised if terms such as “subversive activities” and “separatism” were left vague. The group concluded that such activities had to be organised and involve violence.

Today, the same themes occur in debates about Hongkongers’ right to discuss self-determination or independence.

However, for a few brief hours in April 1987 when the drafting team was in Beijing, those concerns receded. They received unexpected news that Deng wanted to meet them and so they assembled in the Great Hall of the People.

Tam, then a 37-year-old unionist, and lawyer Martin Lee Chu-ming, then a 49-year-old human rights advocate, were among those present.

When China opened up, did it change the world, or did the world change it?

Deng, 82, walked in slowly and shook hands with all 50 members of the drafting committee. The handshaking took so long that he quipped: “It shows I am still all right.”

As they sat down, he told them: “You are all good men. I have many bad habits. One is smoking, one is drinking. Also, I need a spittoon. Spitting contravenes the Western lifestyle most.”

That conversation opener held a deeper, serious meaning. He was alluding to the cultural chasm between the mainland and British-ruled Hong Kong – a world where spittoons were commonplace versus a world shaped by the West.

But to Deng, the two could coexist.

In 1987, Hong Kong was a regional trading hub with a robust economy anchored on manufacturing. Its defining qualities of capitalism backed by the rule of law and societal freedoms would continue under socialist China, Deng said.

By that time on the mainland, the reforms of almost a decade had already stabilised agricultural production, and private enterprises were mushrooming.

Is China suffocating the most vital part of its economy amid US trade war?

Foreign investment was flowing in, and Hong Kong entrepreneurs were among the pioneer investors.

Deng reassured the group that Beijing would allow Hong Kong to keep its way of life for 50 years after the handover. He also promised that if it proved effective, this would continue beyond that period, Tam recalled.

“Deng boosted our confidence that day,” Tam said. “We heard it ourselves, capitalism could be practised in Hong Kong, as part of a socialist country.”

Morale lifted, the committee went home with the double promise of “50 years and beyond” and many more stories of smoking and spittoons to tell.

Over the past four decades, Hong Kong has contributed towards and gained immensely from the mainland’s reforms.

Reform and opening up gave us lots of opportunities, and helped a lot of Hong Kong factory owners to become industrialists

China’s share of Hong Kong’s global trade increased from 9.3 per cent in 1978 to 50.2 per cent (US$530.7 billion) last year.

China has been the city’s largest trading partner since 1985, while Hong Kong was the mainland’s third-largest trading partner last year after the United States and Japan.

Opening up has resulted in China’s gross domestic product expanding more than 80 times from US$150 billion in 1978 to US$12.24 trillion. Over that period, Hong Kong’s GDP expanded from US$18.3 billion in 1978 to US$341 billion.

In 1986, when the stock exchange of Hong Kong was formed by combining four existing bourses, 249 companies were listed with a total market capitalisation of HK$245 billion.

Last year, more than 2,100 companies were listed on the Hong Kong exchange, half of them from the mainland, and their market capitalisation stood at HK$30.54 trillion.

“Reform and opening up gave us lots of opportunities, and helped a lot of Hong Kong factory owners to become industrialists,” Tam said. “Mainland officials were also grateful and said things could not have worked out without Hong Kong.”

Hong Kong is city we aspire to be, top Shenzhen official tells Lam

Lau said: “Reform and opening up propelled Hong Kong’s economic miracle until 1997. It pushed manufacturers to move northwards, while the city transformed by developing service and financial industries.”

After 1997, the miracle got a new lease of life. “One country, two systems” allowed Hong Kong to benefit directly from China’s rapid economic growth, he said, as businesspeople could enter the mainland, make deals and harness the potential of the four special economic zones in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou and Xiamen, all just hours from the city.

Cracks after the crackdown

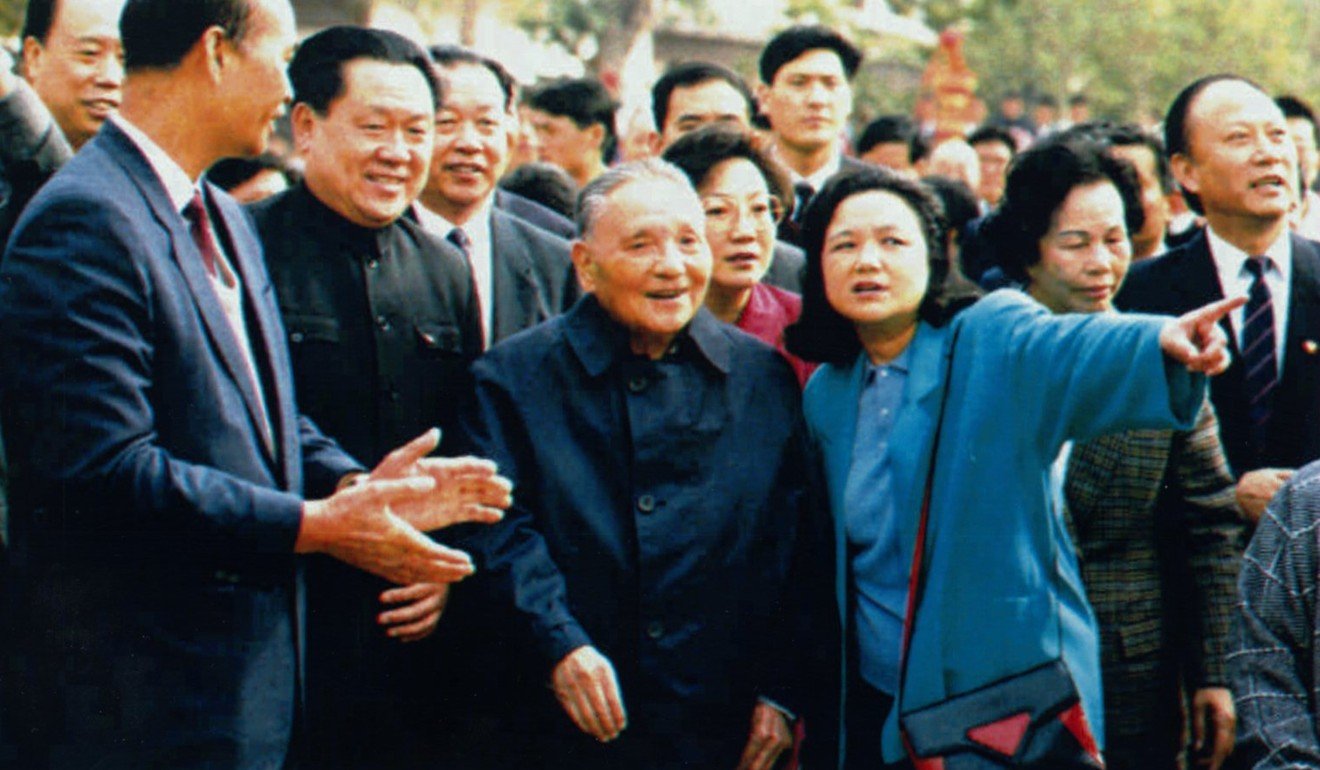

In 1992, Deng’s historic tour of the south gave Hong Kong another boost. The pace of reforms then was flagging and the dark days of the Tiananmen Square crackdown on pro-democracy protesters three years earlier were still fresh in the minds of many, including Hong Kong’s pro-democracy politicians.

Deng visited the Huanggang checkpoint in Futian, Shenzhen, and famously looked at the verdant terrain of Hong Kong’s New Territories for nearly nine minutes.

One official present described his expression as “unforgettable”.

Many interpreted Deng’s lingering gaze as an emotional response, of how precious Hong Kong was in his eyes, a land lost when China was weak and humiliated by outsiders, and how much it mattered now in his grand vision.

Hong Kong eager to play bigger role in China’s reform and opening up

Indeed, Deng reportedly once told a Hong Kong tycoon: “I’ll try my best to stay alive till 1997 because I want to see Hong Kong under China’s rule.”

That was not to be. He died aged 92 on February 19, 1997, less than five months before the handover.

Lau said: “Deng’s tour was to make clear that reforms had to speed up, and Hong Kong’s national importance was given a boost ... The tour also helped to reassure Hong Kong people’s hearts, as a lot of people were worried that China would backtrack on its reforms after the Tiananmen incident.”

An unconfirmed number of pro-democracy protesters died when Beijing cracked down on student-led demonstrators in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989. There is no official death toll, although estimates range from several hundred to several thousand.

Tiananmen jolted many in Hong Kong into fearing that a return to the motherland could be fraught with danger, said pro-democracy stalwart Lee Cheuk-yan.

In some, it reawakened fears they experienced when they left the mainland in 1949 in the wake of the communist takeover. Many in Hong Kong made plans to migrate.

Lee, a core member of the Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, recalled: “It was an episode that completely shattered Hongkongers’ confidence in the 1997 handover.”

The British refused to grant Hongkongers citizenship rights but, much to Beijing’s dismay, tried to inject more democracy into Hong Kong in its last days under governor Chris Patten.

After much wrangling, a limited number of Hongkongers were given British Nationals (Overseas) passports, which brought no automatic right to live or work in Britain.

Xi voices confidence in China's chosen path despite challenges

Former Democratic Party chairwoman Emily Lau Wai-hing said: “Back then I often said, ‘What does BN(O) stand for? It’s Britain says ‘no’. They jumped up and down. They really disliked me.”

Lee and the alliance made it their mission to mark the Tiananmen anniversary, holding a June 4 vigil in Victoria Park every year. Hong Kong and its much smaller neighbour Macau are the only places in China allowed to express sadness, regret and anger over that dark episode.

Lee said the vigil had become “symbolic of Beijing’s tolerance for the ‘one country, two systems’ principle”.

Observers say the annual vigil also inspired and honed Hongkongers’ ability to organise protests, and two demonstrations stand out.

On July 1, 2003, about half a million people took to the streets to protest against a proposed national security bill Hong Kong was required to introduce under Article 23 of the Basic Law.

The bill, meant to prohibit acts of treason and subversion, was viewed by many as an attempt to curb civil liberties.

The bill was shelved. New People’s Party chairwoman Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee, then the security minister, believes the opposition to the bill soured Hong Kong’s relationship with Beijing, which was “disappointed and disturbed”.

Led by young student activists, the Occupy protesters demanded freer elections, criticised the screening of candidates for the city’s chief executive, and expressed unhappiness at the way Beijing was imposing its will.

Whither ‘one country, two systems’?

Even as China made strides economically and Hong Kong benefited, politically the unease lingered, waxing and waning over the years.

Occupy leaders on trial: who they are and what they’re accused of

Today, politicians from both sides of the divide in Hong Kong agree that the city will always be strategically important as China continues with new initiatives to further open its economy.

What they disagree on is whether Beijing remains committed to the arrangement Deng envisioned, and the way forward.

Pro-democracy politicians maintain Beijing’s increasing involvement in the city’s affairs has strayed from his original thinking.

The inside story of the propaganda fightback for Deng’s reforms

Pro-Beijing politicians counter that the central authorities have been making only minor adjustments in the face of challenges such as the rise of localism and pro-independence sentiment.

The Hong Kong government wielded existing legal provisions but pro-Beijing politicians say the episode underscored the need to move ahead with Article 23.

Mallet had hosted a talk by HKNP leader Andy Chan Ho-tin at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club, despite strenuous objections from local and Beijing officials.

Ban on journalist risks undermining business confidence, UK minister warns

The saga brought to mind the concerns of the Basic Law drafters in 1987, on what might constitute support for separatism.

For political activists like Nathan Law Kwun-chung, 25, the government’s recent actions are just the latest in a series of moves to curb freedom of expression and people’s rights, thereby undermining “one country, two systems”.

An Occupy leader, Law was elected to the Legislative Council in September 2016, but was ousted in July 2017 with five others for taking their oaths improperly.

Martin Lee says the “one country, two systems” model has deviated from Deng’s design. Lee saw Deng’s promise of “no change for 50 years” to mean not only a safeguard for the city’s way of doing things, but also that the mainland would catch up on the rule of law, freedoms and human rights.

Li Keqiang underlines China’s ‘opening up’ vow as Pacific leaders meet

Lau, more optimistic, argued that in the ongoing trade tensions between the US and China, Hong Kong’s value to Beijing had become even more obvious.

He said Hong Kong’s pan-democrats needed to show they were willing to be a “loyal opposition” in order for reconciliation over political tensions of the past several years to take place.

But former Democratic Party chairman Albert Ho Chun-yan feared too much damage had been done. Taiwan would no longer look to Hong Kong as a model, he said.

Taiwan already elects its own president, whereas Hong Kong’s chief executive is still selected by 1,200 people.

Lee said all he wanted now was to safeguard Deng’s model of a high degree of autonomy. A recalibrating to give weight to “two systems” rather than just “one country” was in order, he said.

“I just want Deng’s ‘Chinese dream’ to be achieved. That’s real patriotism,” the 80-year-old democrat said. “I am not asking for more than what was promised.”

Inside China podcast: 40 years of economic ‘reform and opening up’