Film on Islamic State screening in Hong Kong aimed at stopping domestic helpers from radicalising

Documentary backed by Indonesian consulate in city meant to fight extremism

A documentary on Islamic State militancy is screening this weekend in Hong Kong and Macau as part of the Indonesian consulate’s heightened efforts to prevent domestic helpers from being radicalised.

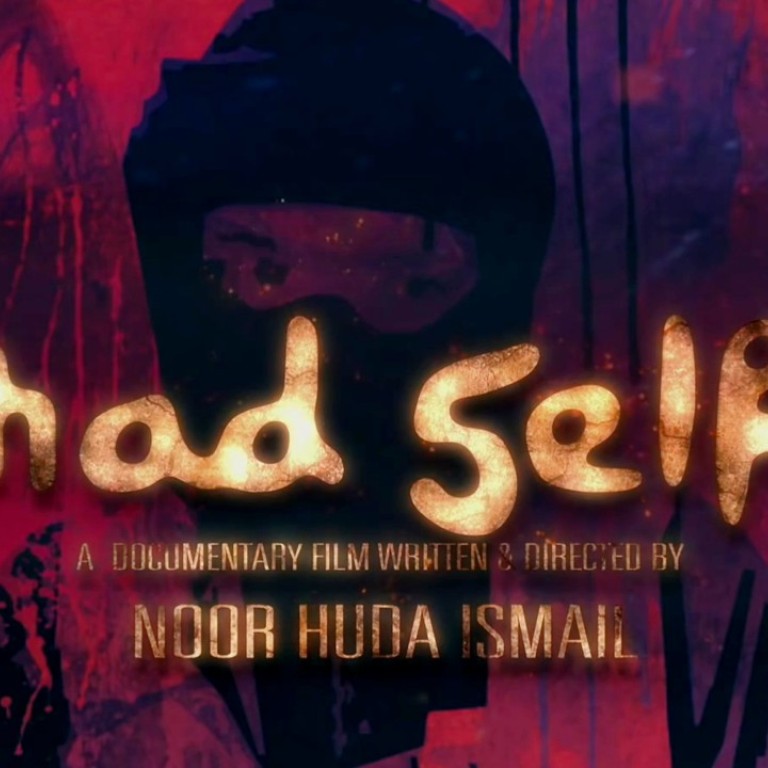

Noor Huda Ismail, a researcher on radicalism and director of the documentary Jihad Selfie, came to Hong Kong and said raising awareness was the first step to combat extremism.

“Think as a domestic helper,” Noor told the Post. “You are lonely, you have the money, you need to bond with something, and some people bond with this,” he said, referring to a mobile phone he held.

Awareness comes first, then the government has to come up with targeted messages

In Hong Kong, an Indonesian domestic worker is able to make up to four times the salary he or she would receive back home, but many face isolation and sometimes abuse.

“Some are clearly attracted to this ideology because of social issues,” he added. “Thousands of helpers living here divorce every year. Their involvement has usually to do with romance ... I do not deny they radicalised, but it’s not as simple as that. They usually have a social issue first and then they take refuge in religion.”

Noor said he hoped those viewing the documentary could spread the word in the community. Question-and-answer sessions were to follow each screening.

“They could act as agents of change within their own community, taking ownership of the issue,” he said.

Noor believed it was necessary to work closely with workers’ associations and interests groups. “Awareness comes first, then the government has to come up with targeted messages, have a hotline service and be able to identify the signs.”

In Jihad Selfie, Noor examined the impact of social media campaigns by the jihadist group Islamic State, also known as ISIS, on Indonesians. He followed supporters in Indonesia, Egypt and along the Syrian border, and interviewed returned Islamic State fighters.

“They see propaganda on social media, they think life there is good. But when they get there, they realise it’s terrible,” he said, noting he had met dozens of former fighters.

“We need to come up with a nuanced understanding on this matter. It can’t be black and white.”

Could an Islamic State ‘virtual caliphate’ be defeated?

And understanding is not tantamount to support, he added. “We need to have a conversation about it, an international conversation. Not just say: ‘OK, they travelled there, let’s throw them in jail.’ ISIS will collapse soon.”

Noor said the group’s declining strength in parts of Iraq and Syria offered further reason to advance the conversation.

“Mosul has fallen, Raqqa is about to fall, and what happens after that?”

The former journalist is now working on a second documentary, Terrorist Whisperer, expected to be released next year. It looks at life under Islamic State for people who joined it.

In the new film, Noor said, he wanted to “reflect on why people leave and what they learn”. He added he was trying to include more women in the project.

About 20 Indonesian domestic workers on Hong Kong police watch list over Islamic State links

One such returnee is Machmudi Hariono, 40, alsovisiting to share his experience with domestic helpers in Hong Kong and Macau.

Machmudi fought in Mindanao in the Philippines between 2000 and 2002, and was arrested after returning to Indonesia. Although he does not regret his time on the battlefield, Machmudi expressed disagreement with the use of violence in peaceful places, such as launching terrorist attacks in Indonesia.

He claimed that Islamic State had made the rules of war worse, adding: “I am now on a mission to tell my friends not to fight because I don’t think that is a solution.”