Exclusive | Maternity leave in Hong Kong: can Chief Executive Carrie Lam bring city in line with Singapore and South Korea without riling the business community?

With the city leader set to allow women to take 14 weeks off after giving birth, employers say the latest pro-labour policy will cause them major headaches

Mother-to-be Erica Wong Wing-yan heaved a sigh of relief when her company increased maternity leave from the statutory 10 weeks to 14 weeks this year.

The Hongkonger and her husband, both 33, are expecting their first child in January and Wong hoped to breastfeed her baby for at least three months.

That would have been almost impossible if she returned to her job as a luxury boutique supervisor after only 10 weeks’ leave. It would be hard to take even 15 minutes off to pump milk, she said, because during peak hours the store is so busy it looks like “a war scene”.

Her company’s new maternity leave policy will let her breastfeed at home for three months, and she will try to continue afterwards. The World Health Organisation recommends at least six months of exclusive breastfeeding.

“My goal is actually limited by the length of maternity leave in Hong Kong,” she said. “The health of my baby is my utmost concern.”

Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor is expected to announce increased maternity leave of 14 weeks when she delivers her policy address next Wednesday.

It is a move not all employers will welcome, especially small to medium-sized companies which make up 98 per cent of the city’s businesses and are already complaining about the rising cost of doing business and the labour squeeze.

But Hong Kong is also short of babies.

Secretary for Labour and Welfare Dr Law Chi-kwong pointed out recently that the city’s declining fertility rate – of just 1.13, measured by babies per female resident – was possibly the lowest in the world. The fertility rate has been below 2.1 – the level at which a population remains steady – for more than three decades.

There were 56,500 babies born in the city last year, down from 70,900 a decade earlier.

The government is anxious to address the reasons couples are putting off having babies, or not having them at all. The short maternity leave is a factor, and compares poorly with longer leave in many other places, including Britain, Sweden, Singapore and South Korea.

Some start-ups, multinational corporations and banks in Hong Kong have more generous maternity leave policies for working women.

British mother Nabeela Shamsuddin, who has lived in Hong Kong for two years, is fortunate because her company, a consultancy start-up, has given her six months of fully paid maternity leave.

Married to a fellow Briton for five years, Shamsuddin, 28, had their first child, Isaac Kareem Hassan, in August and has been at home since.

She wakes up three times a night for an hour each time – at 1am, 3am, and 6am – to feed and change the baby. Her husband, who has a full-time job in finance, also helps out before and after work.

“It has been extremely exhausting,” she said.

Having a baby means not only feeding and changing nappies through the day and night, but dealing with unexpected illness, going for regular check-ups, and staying on top of parenting as the infant develops and changes every week.

Shamsuddin knows her company is “very generous”, but thinks it would be ideal for new mothers to have a year off to recover fully from the mental and physical demands of giving birth and caring for a newborn.

She said Hong Kong employers who oppose giving women 14 weeks’ maternity leave reflect “capitalistic greed against humanity”.

Shamsuddin and Wong count themselves more fortunate than the tens of thousands of working women who get the statutory minimum of 10 weeks’ maternity leave on 80 per cent pay.

How backward are Hong Kong’s family-friendly policies?

Sources said that in extending maternity leave to 14 weeks, the government would offer employers subsidies to cover the additional costs, up to a limit.

This will finally put the city on par with other places in the region that already meet the International Labour Organisation (ILO) recommendation of at least 14 weeks’ maternity leave.

Hong Kong’s maternity leave has not been updated for 48 years, though the terms have changed over the decades.

When it was first included in the Employment Ordinance in 1970, maternity leave was given without pay. This was changed in 1981 to provide a working mother two-thirds of her daily wage, and in 1995, four-fifths.

A study by the ILO in 2014 found that 98 out of 185 countries and territories studied (53 per cent) – provided maternity leave of 14 weeks or more, and Hong Kong was among only 27 (15 per cent) which provided less than 12 weeks.

In Asia, the study found only Brunei, Malaysia, Nepal, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines had less than 12 weeks’ maternity leave.

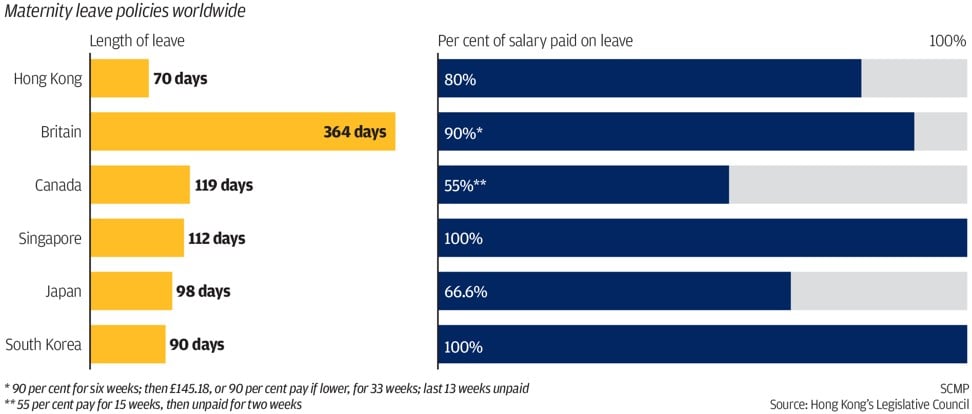

Britain offers 52 weeks; Singapore, 16 weeks; and South Korea, 90 days, with varying pay terms.

Singapore, which also has a low fertility rate, extended fully paid maternity leave to 16 weeks in 2008.

For the first and second child, employers bear the cost of maternity leave, although they are reimbursed by the government for the last eight weeks, subject to a ceiling of S$10,000 (HK$56,200) for every four weeks. For the third child and subsequent children, the government reimburses the cost of paid leave for the full 16 weeks, subject to the same ceiling.

In Britain, women are entitled to 52 weeks’ leave, receiving 90 per cent or less of their pay for most of that period, with 13 weeks being unpaid leave.

Among Scandinavian countries, Sweden is known to be exceptionally generous, providing parental leave of up to 68.6 weeks – 480 days – which is shared by both parents and funded by the country’s Social Insurance Agency.

“Hong Kong is a city that is not friendly to working mothers. We lag far behind our peers in family leave policies,” lamented Fiona Nott, chief executive of the Women’s Foundation in Hong Kong, a non-profit organisation dedicated to improving the lives of women and girls.

The foundation said government subsidies help in the short term, but companies should also be looking to shoulder the full cost of maternity leave in the longer term and embrace family-friendly policies that enable women to thrive in the workforce.

“Numerous studies show that greater gender diversity in the workplace leads to better business outcomes,” she said. “So policies that help support women in the workplace are actually good for Hong Kong overall.”

The labour force participation rate among women in Hong Kong stood at only 55.4 per cent as of August this year, compared with 68.7 per cent for men, according to the Census and Statistics Department. The female participation rate has risen by only 6.7 percentage points since 1998.

Nott hoped Hong Kong would eventually go the way of Sweden and other countries that have replaced maternity and paternity leave with parental leave which either parent can use.

Stand-off against the business sector

Working mothers will welcome having more time with their babies, but in raising maternity leave, Hong Kong leader Lam will probably rile the business sector, in an address described by one of her cabinet members as “pro-family” and “pro-labour”.

There is already tension between her administration and the sector over her plans affecting the Mandatory Provident Fund (MPF) retirement scheme, which she is also expected to touch on next week.

Pressing ahead with longer maternity leave may make matters worse.

Already, Jimmy Kwok Chun-wah, the Federation of Hong Kong Industries chairman, has said that “responsible workers” may not want 14 weeks of maternity leave.

If the government wants to give women more maternity leave, he said, it should subsidise employers in full. He said employers were more concerned about finding manpower to cover staff who go on such long leave.

“The government should help employers find the substitute staff and pay their wages,” he said. “There are some industries where bosses may not be able to find substitute staff easily. What can they do?”

He said Britain could afford to provide more maternity leave because the shortage of manpower there was not as serious as in Hong Kong.

Liberal Party leader Felix Chung Kwok-pan agreed that the government should fully reimburse the additional cost of providing longer maternity leave.

“The government enjoys a tremendous financial reserve and it should not just ask the business sector for more money, especially against the backdrop of the ongoing trade war between the United States and China,” said the lawmaker who represents the textile and garment constituency.

Chung conceded that the extra cost of providing longer maternity leave was “not a big deal” given the small pool of women who would benefit, but he said the sector would stand firm as a matter of principle because Lam’s administration has introduced pro-labour policies one after another.

He cited the proposed MPF changes and the plan to extend paternity leave from three days to five.

We are talking about just around 30,000 working mothers who will benefit every year. The extra subsides would not be a huge amount

“Just give us a break,” Chung said.

Lawmaker Vincent Cheng Wing-shun said he understood the maximum government subsidy to cover the cost of extending maternity leave was likely to be between HK$40,000 and HK$50,000, which means more than 80 per cent of employees would be covered. Median monthly pay is HK$18,000.

Cheng, of the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, believed the cap could ease employers’ concerns, though he hoped the government would go a step further and subsidise the full salary of working mothers, instead of just 80 per cent.

“We are talking about just around 30,000 working mothers who will benefit every year. The extra subsides would not be a huge amount,” he said.

It’s not just about maternity leave

Observers of Hong Kong’s declining birth rate point out that inadequate maternity leave is just one of many reasons couples are not having babies.

For working mothers, a big issue is where to leave the baby when they return to work, because there is a severe lack of childcare services and family-friendly workplaces.

Those who cannot afford or prefer not to hire a live-in helper find it nearly impossible to place young children in day crèches. The number of places for children below two years old has dropped from 1,530 in 1995 to 747.

The Post called six out of 12 aided childcare centres which provide such services, and all were full. Most said they had no vacancies until next August or September. A Mong Kok centre with 99 places said more than 600 babies were already in its queue.

Professor Paul Yip Siu-fai, chair professor of population health at the University of Hong Kong, said the provision of childcare services – which could free housewives to return to the workforce and improve the early development of children – was “highly insufficient”.

He said the lack of childcare options affected single-parent families more, because single mothers could not return to work if they had nowhere to leave their children.

The poverty rate for single-parent households is double the overall level in Hong Kong, he said, but such a difference was not evident in Sweden, where single parents could go to work freely.

Yip, who is leading a team of experts commissioned by the government to study the long-term development of childcare services, said extending maternity leave was a good start, but the government and employers should provide more childcare services, especially near workplaces.

“A female labour force participation rate of some 50 per cent is undesirable as it would be around 70 per cent in many other places,” he said.

Erica Wong’s husband, Hanson Cheng Hon-sang, said it was good for the government to offer pregnant women an extra four weeks of maternity – though he added 14 weeks was still far from enough.

“She needs time to recover ... and at least she would have more time to take care of the baby,” he said. “I would also be more relieved as I go to work.”

He said the government should consider extending paternity leave to a week.

“There are so many things to do after the baby has arrived,” he said.

Additional reporting by Kimmy Chung