Watch your carbon footprint: Hong Kong’s getting hotter, as climate change makes its presence felt

- All signs point to more climate-related trouble ahead, unless change happens soon

- Concern groups want robust government action, individual lifestyle changes too

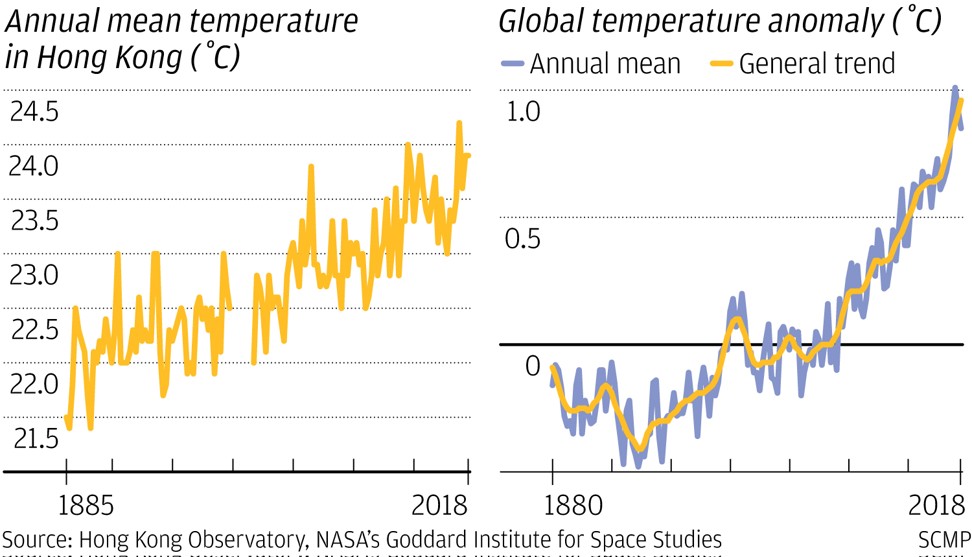

Hong Kong saw its warmest year on record in 2019, which is also likely to be the second or third warmest globally, according to the Hong Kong Observatory and the World Meteorological Organisation.

The decade ended with record heatwaves across the northern hemisphere, while Australia fought some of its worst wildfires in decades which have left at least 28 people dead and destroyed more than 2,000 homes in the state of New South Wales alone. Half a billion animals have been affected, with millions estimated to have perished.

Climate change has been blamed for the intensity of the Australian fires as well as for natural disasters such as the typhoons that batter Hong Kong every year. Typhoon Mangkhut in 2018 was the most intense storm in the city’s history. Zoe Low looks at how the climate crisis will impact Hong Kong and what the government and individuals can do about it.

Why is Hong Kong getting hotter?

Earth’s average surface temperature has risen about 0.9 degrees Celsius since the late 19th-century, driven by the emission of greenhouse gases – including carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and ozone from the burning of fossil fuels – which trap heat in the atmosphere.

It is “extremely likely” the warming trend is caused by emissions from human activity, according to a 2015 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body which assesses the science related to climate change.

Sham Fu-cheung, chief experimental officer at the Hong Kong Observatory, says: “There is a clear upward trend in Hong Kong’s temperature due to the impact of climate change.” Less cold air along the southern coast of China and a weak northeast monsoon have also led to warmer ocean surface temperatures, which in turn is contributing to the warm weather.

Last year, Hong Kong’s average temperature was 1.2 degrees Celsius higher than the “normal” average temperature of 23.3 degrees Celsius based on the benchmark of 30 years from 1981 to 2010, the Hong Kong Observatory says.

There were 33 “very hot days” and only one “cold day” last year – the lowest number of cold days since records began in 1884.

Hong Kong can step up fight against global warming by declaring a ‘climate emergency’

The city’s largest source of emissions comes from electricity generation as coal is still the main source of fuel, accounting for 48 per cent.

Natural gas, which is cleaner than coal, currently accounts for almost 30 per cent and is expected to reach 50 per cent this year. Non-fossil fuels, including imported nuclear power, account for 25 per cent, while only 1 per cent is from renewable energy sources such as solar power.

Almost 70 per cent of Hong Kong’s emissions come from energy generation, 90 per cent of which is used to provide power supply to buildings. Another 18 per cent comes from vehicle emissions.

“More people are taking short trips abroad and this has also led to an increase in emissions, especially with the increase in budget flights in Asia,” Ringo Mak Wing-hoi, co-founder of climate change concern group 350 Hong Kong, says.

How does climate change affect Hong Kong?

Aside from rising temperatures, climate change has been blamed for an increase in extreme weather events including storms and droughts worldwide. Warmer weather has caused the Arctic and Antarctic ice shelves to melt, leading to a rise in sea levels, which, combined with stronger storms, could lead to intense flooding. All of this can impact Hong Kong.

Typhoon Hato in 2017 led to losses totalling HK$40.3 billion across Hong Kong, Macau and Guangzhou. In 2018, Typhoon Mangkhut brought heavy destruction to communities along Hong Kong Island’s east coast. More than a year later, two housing estates in Heng Fa Chuen, one of the worst-hit areas, are still grappling with the after-effects of Typhoon Mangkhut, with their insurance companies increasing fees by almost three times.

The food Hongkongers eat could also be affected, Karen Ho, head of corporate and community sustainability at global conservation body WWF-Hong Kong, says. “Some species we eat might decrease in number or go extinct,” she says. Staples such as wheat, rice and maize could become scarce due to unpredictable weather and temperatures, while some fruit such as avocados and strawberries are also believed to be at risk.

Citing a new study by US-based NGO Climate Central, Ho and Mak warn that if the rise in global temperatures is not kept within 1.5 degrees Celsius – as set under the Paris Climate Agreement which came into force in 2016 – vast tracts of the Pearl River Delta can expect yearly flooding. The Paris Agreement is a global convention aimed to combat climate change.

Typhoon Mangkhut felled 46,000 trees in Hong Kong. Will they end up in landfill?

The Climate Central study estimates that 1.3 million Hongkongers could be hit by flooding every year in areas such as Tai Po, Sha Tin, and at the Hong Kong International Airport. If that happens, Ho says, “nothing can be done, no matter how much money you have”.

How to shrink the carbon footprint?

In 2018, the average Hongkonger released about 5.9 tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere. This is known as the carbon footprint. Individuals, organisations, and communities have their carbon footprints determined by their use of resources and the amount of greenhouse gases generated to support human activities. It is calculated by considering the burning of fossil fuels, such as from driving or flying, the production of food, clothes, or other items, and the distances these goods have to travel to reach users.

Under the Paris Agreement, Hong Kong has pledged to shrink its carbon footprint to between 3.3 and 3.8 tonnes by 2030. This requires officials to take strong action to combat emissions, Mak and Ho say.

At the government level, declaring a climate emergency – as has been done in London, New York, and the European Union parliament – will provide an overarching framework for various bureaus to work together to combat the climate crisis, Ho says. The climate emergency campaign, started in 2016 in Australia, has since gained traction in 1,261 cities across 25 countries.

What action is Hong Kong taking?

Hong Kong is encouraging residents to switch to electric vehicles by providing subsidies to housing estates to upgrade parking facilities for such vehicles. It is also subsidising electric ferries, buses, and trucks, in addition to switching from coal to natural gas.

Change needs to come from government policies and moving away from fossil fuels entirely

However, Mak and Ho say the government needs to find more sources of renewable energy, such as solar or wind power, as natural gas is a fossil fuel and is only marginally cleaner than coal.

The results of a public engagement exercise on the city’s long-term decarbonisation strategy are also expected in the first half of this year. But Mak says the questions are “too basic, showing a lack of determination by the government to tackle climate change”.

“Change needs to come from government policies and moving away from fossil fuels entirely,” he says.

Can individuals do anything to help?

Although Mak wants significant top-down policy change, he thinks individuals can play their part too. For a start, people can take shorter showers to save energy used to heat water, drive less and carpool.

“While flying less is hard for people, perhaps they can take fewer, longer overseas holidays, rather than going on many short trips, to cut emissions,” he says.

We are becoming more aware of the impact of climate change, and if we don’t change our lifestyle, that’s just selfish

Ho says individual lifestyle changes are important not only in Hong Kong but across the globe. One easy way to start is by eating less meat, particularly beef, because raising cattle uses 83 per cent of global farmland and accounts for 60 per cent of emissions in agriculture.

She wishes there was more awareness of the growing number of climate refugees – those displaced by sudden changes in their environment. In 2017, weather-related disasters displaced 18.8 million people, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre.

“We are becoming more aware of the impact of climate change, and if we don’t change our lifestyle, that’s just selfish,” she says.