Exclusive | Jane Goodall on calling Interpol, the far right and eating your fingernails

- Best known for her work with chimpanzees, renowned animal expert and activist says hope for planet lies in educating young to be stewards

- She champions indomitable human spirit but warns mankind against running itself into extinction

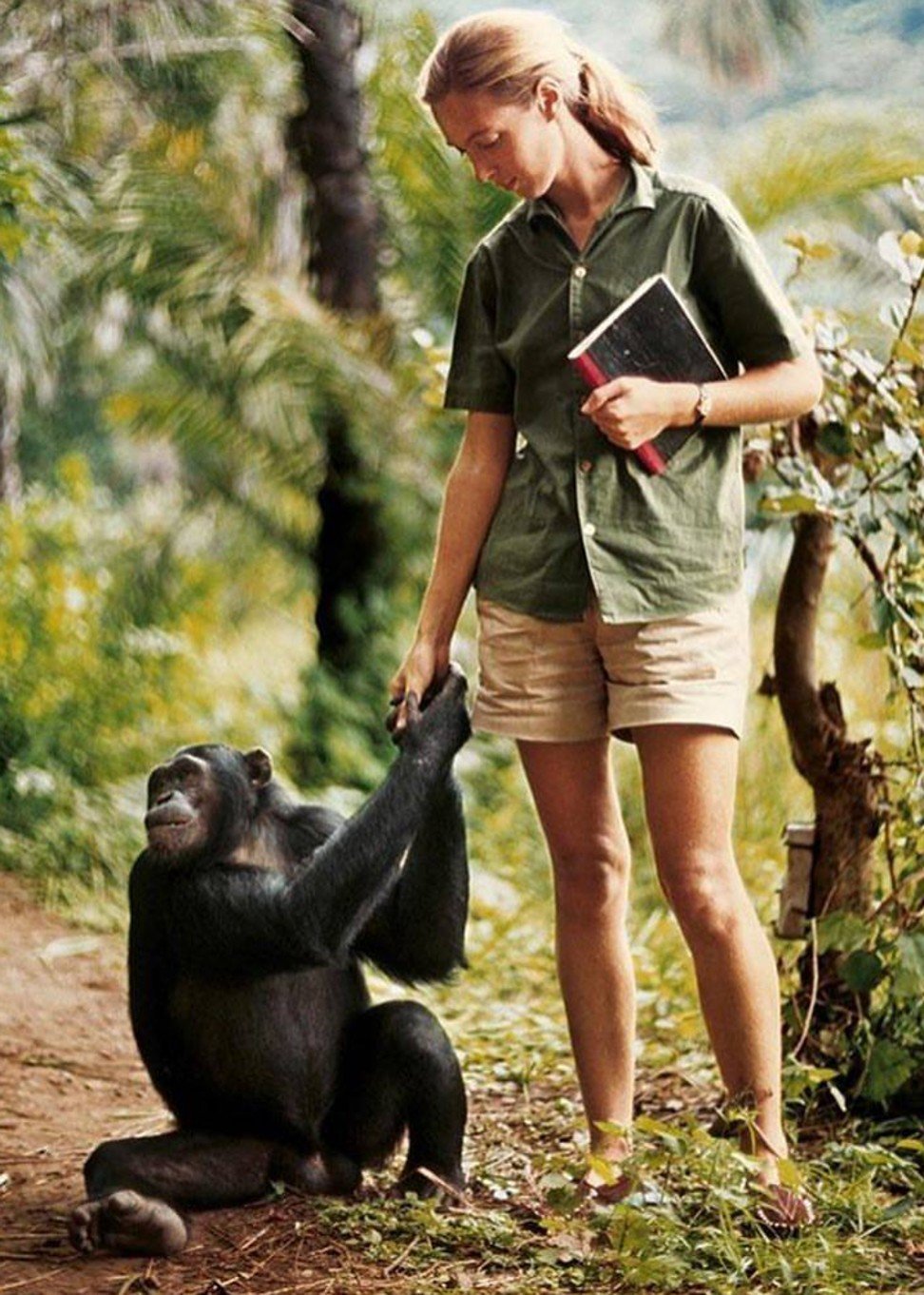

From a very early age, Jane Goodall dreamed of going to Africa, living with wild animals and writing books. She achieved all that, and considerably more.

As a result of her work with chimpanzees in Tanzania, Goodall, now 84, has written more than 20 books and has been the subject of dozens of documentaries. Along the way, she earned a PhD in animal behaviour from Cambridge and has been made a United Nations Messenger of Peace, as well as a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

Little about Goodall’s background suggested she would become a global superstar of conservation. She grew up in Bournemouth in the south of England and became enamoured of animals after reading Hugh Lofting’s The Story of Doctor Dolittle. Coming from a modest home, she was unable to attend university. But in 1956, after going to secretarial school and working as a typist, she received a letter that would change her life: a friend in Kenya asked if she would visit.

Having always wanted to visit Africa, Goodall dropped everything. Taking a job as a waitress, she saved up for a passage to Kenya, arriving in 1957. There, she met the palaeoanthropologist Louis Leakey, whose work had helped demonstrate that human beings evolved in Africa. Leakey had a curious proposition: he asked Goodall to go to Tanzania to study chimpanzees. By studying primates, Leakey thought, humanity could understand more about its ancestors. Goodall accepted Leakey’s suggestion, and it changed her life.

This month, more than 60 years on, Goodall visited Hong Kong on behalf of her organisation, the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI). Established in 1977 with the aim of protecting chimpanzees and their habitat, JGI’s mission has grown to incorporate a broad range of conservation and education programmes worldwide, with activities in 80 countries and territories, including Hong Kong.

Goodall met the Post to explain her world view, her work in the 21st century, and what she hopes to achieve by travelling a gruelling 300 days of the year.

You arrived at Gombe National Park in Tanzania in 1960. What was your mission?

Louis Leakey asked if I would be prepared to go and study chimpanzees – not just any animal, but the one most like us. I got to Gombe on the edge of Lake Tanganyika, and put up my little tent. My mother was with me at that time because the British authorities thought it was a crumbling outpost of the British Empire, and they refused to take responsibility for a young girl on her own, so mum volunteered. For months the chimpanzees ran away as soon as they saw me – they’d never seen a white ape before. I was actually learning quite a lot, but it wasn’t what I wanted: I wanted them close up. As the chimps gradually lost their fear, I began to get to know them.

Of all the things you learned from chimpanzees over the years, what lessons have meant the most to you?

It was fascinating to see their very different personalities; they’re just as different from one another as we are. The breakthrough observation was of one chimpanzee, David Greybeard, who first began losing his fear. I saw him breaking off grass stems and pushing them into termite mounds and eating the termites. I saw him break off a leafy twig and he had to strip the leaves in the side branches to make a tool.

At that time it was thought that only humans used and made tools. It was science that thought this, but if you had asked the pygmies living in the forests of Congo, they could have told you chimps used tools! This was what interested National Geographic, and they sent a photographer and filmmaker. Finally, because it was being documented, the snooty scientists who said: “Why should we believe this young girl, she hasn’t even been to college”, had to believe. What’s striking is how like us the chimps are: communication; gestures just like us, such as kissing, embracing, holding hands, patting one another; swaggering and shaking their fists. And this long childhood, five years of suckling. Just like our children, chimpanzee children have a lot to learn, and they learn by observing and practising what they have seen.

Worldwide, your work is carried on by the Jane Goodall Institute. Could you explain how your vision of community-centred conservation works?

In 1986 I helped to organise a conference of people studying chimpanzees in seven different locations across Africa. It was utterly shocking that right across Africa, the forests were disappearing, chimpanzee numbers were dropping. I learned a lot about the problems faced by the chimps, but I also learned a lot about the problems faced by the human communities living in and around chimpanzee habitats. Crippling poverty, the lack of good health and education, and of course the ethnic violence.

Rhino horn is just like eating your fingernails. It’s the same material, keratin

I got my PhD as a scientist, but I left the conference as an activist. It hit me: if we can’t help these people to find alternative ways of living that don’t involve cutting down the forest to grow food or make charcoal, then we can’t even try to save the chimps. And so it was in 1994 that the Jane Goodall Institute began our programme, which we started off calling Take Care. It’s a holistic programme for empowering women and getting scholarships to keep girls in school. It’s been shown all around the world that as women’s education improves, family size tends to drop, and this is desperately important. We’re also helping to restore fertility to the overused land without chemicals, and pushing the Tanzanian local government to help with education and health. We started with 12 villages around Gombe; we now have the programme in 72 villages throughout the remaining chimpanzee range in Tanzania.

Hong Kong remains a hub for the trade in endangered animals and ivory. [Goodall cuts in: “and pangolins!”] How have you been involved in the fight against this trade?

It’s something that JGI worldwide is involved in, because animals are disappearing. Elephants and rhinos right across Africa are facing extinction. Pangolins are the most frequently trafficked animal on the planet, because people mistakenly think their scales are medicinal and they’ll protect you in childbirth.

People believe that rhino horn is good for all kinds of ailments – but rhino horn is just like eating your fingernails. It’s the same material, keratin. And of course there’s ivory, which is carved into trinkets. So we have to better arm the rangers in Africa.

If we can’t get young people to be better stewards for this planet than we’ve been, what’s the point of anything?

We have to get Interpol into catching the ringleaders who are very high up – sometimes in the government. But we also have to work on the demand. If people don’t want to buy ivory trinkets, there won’t be a market for the ivory. If people understand that rhino horn is no different from fingernails, maybe they’ll start to see sense.

In Hong Kong, we started Roots and Shoots [JGI’s schools programme] some time ago. It didn’t take off very quickly, but now there are 77 schools involving young people of all ages. I was with little kindergarteners this morning and then I was with 12, 13, 14-year-olds, and they are so passionate. They’re learning about climate change and they’re learning about animal welfare – and this is why I travel 300 days a year. If we can’t get young people to be better stewards for this planet than we’ve been, what’s the point of anything?

You have said previously that China could be instrumental in helping to reverse the damage humans have done to the planet. What is China doing that gives you hope?

China is now developed sufficiently to begin protecting its own environment. But just like European colonialism, just like the big corporations, China is now seeking outside for the natural resources it needs for its own development. I keep hearing, “China’s eating the planet” and “China is doing this, that and the other” – and it’s true. But they’re not doing any different from what we’ve done. I can’t point a finger, I’m in a glasshouse: British colonialism was as greedy as any of them.

I can’t point a finger, I’m in a glasshouse: British colonialism was as greedy as any of them

It was very encouraging that China banned importation of ivory; but it’s very distressing that they’ve lifted the ban on importing rhino horn and farmed tiger bones, but I’m still praying for a miracle and that the decision will get reversed. [The day this interview took place, China announced it was reversing the decision. Ding Xuedong of China’s State Council announced on November 12 that the order to undo the 25-year ban had been postponed.]

The unifying theme of your books – perhaps even your career – is hope. How do you remain optimistic for the future of our planet?

Well, it’s sometimes a little difficult, especially recently – this swing to the far right politically is extremely disturbing. It’s happening in America, it’s happening in Europe, it’s happening all over Africa. There’s an unlimited desire for material goods, and it’s absurd to think that we can have continued economic development on a planet of finite natural resources. Climate change is with us, and it’s being felt all over the world – in Hong Kong you just had this terrible typhoon, and hurricanes are getting more frequent and more violent; there’s flooding, droughts and terrible wildfires.

But if we lose hope, if we give up, then that’s the end. I believe we’ve got a window: if we get together, we can start at least healing some of the scars. We’ve only got this one blue and green beautiful planet. So how can the most intellectual species be trashing it the way we are? It seems to be because there’s been a disconnect between this clever, clever brain and the human heart.

I know there are millions and hopefully billions of people all wanting to help, but not perhaps understanding that collectively, every single day, every one of us makes a difference. But now we have social media to reach out to people all around the world who care about a particular issue, and we could never do this before. We have people in hundreds of countries joining in one day.

Nature, when allowed, will come back

And finally there’s the indomitable human spirit. The people who tackle the impossible and never give up. I meet them as I travel around the world. I see amazing projects, I see places we have destroyed and made ugly. Nature, when allowed, will come back. Animals on the brink of extinction have sometimes recovered when they’ve been given another chance. I know we’re in the middle of the sixth great extinction, but we can stop it being total.

And if we don’t? Never mind all the animals – we too will no longer be able to inhabit this planet.