Only 287 public places in Hong Kong to provide 46,000 special-needs children with vital therapy

Advocacy group calls on government to boost funding for training and rehabilitation services, to help reach more youngsters in need

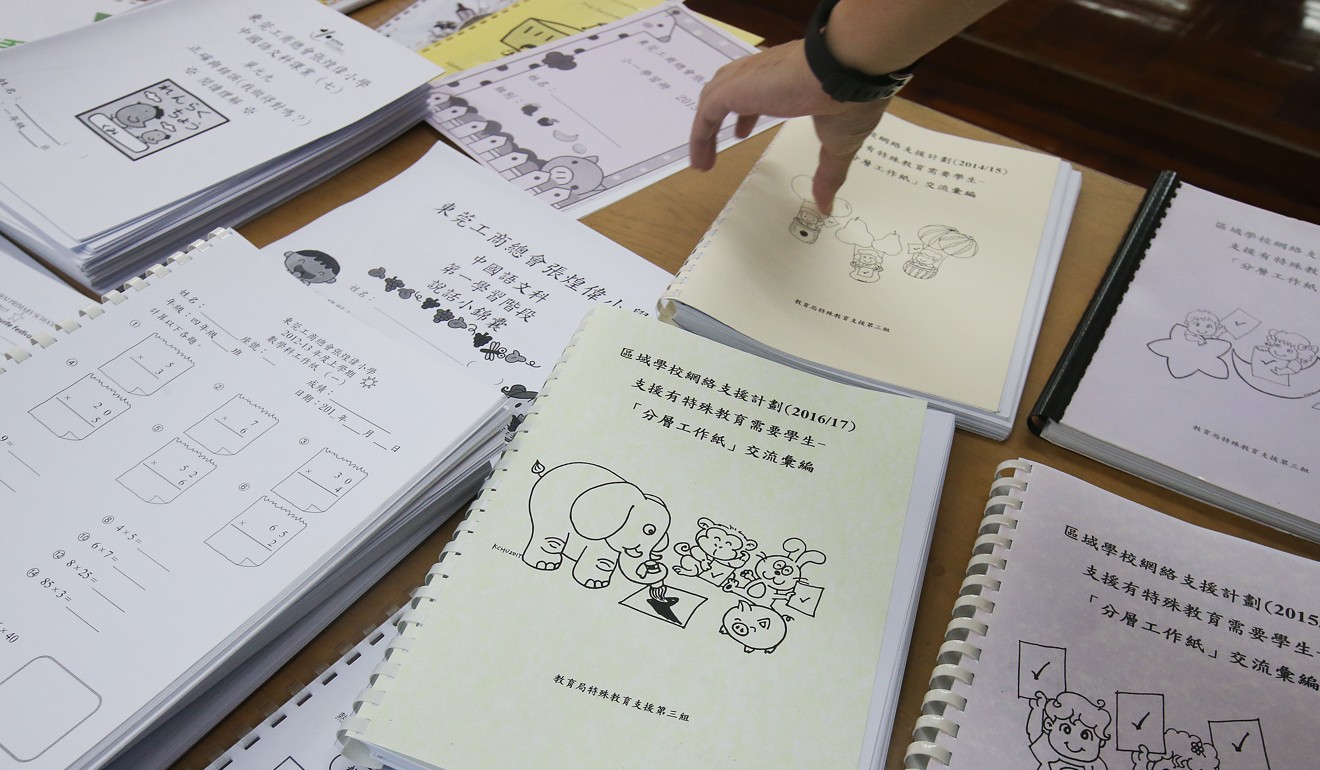

Fewer than 300 places are available at Hong Kong’s public community centres to serve 46,000 special-needs schoolchildren in need of vital support services, a study by an advocacy group has revealed.

SEN Rights Association called on the government to boost spending on rehabilitation and training for youngsters above the age of six, to make the services more accessible, stable and affordable.

The study was released on Wednesday and came as a 52-year-old grandmother was arrested for the alleged murder on Sunday of her six-year-old grandson in Wan Chai. The child was suspected to have had special educational needs, raising concern about sufficiency of support services in Hong Kong.

The association found that 124 community centres provided public services for special-needs children last year, but that number fell to 119 this year. These centres collectively offered 287 places for activities including small-group training and speech therapy. For day-care services, only one place was available.

The slots were far from sufficient, the association said, for the estimated 46,075 children suffering from conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and dyslexia.

That figure was based on a study by the government’s Education Bureau that found 6.2 per cent of Hong Kong pupils had special educational needs in the last academic year.

Hong Kong’s special needs children not getting the therapy they need past the age of six

Ho Cheuk-hin, an organisation officer for SEN Rights Association, said the Labour and Welfare Bureau should expand services to cover all special-needs children above the age of six, and extend programmes offered by six parent resource centres to all of the city’s 18 districts.

Non-governmental agencies running social services for special-needs children above the age of six currently receive no subsidy from the Social Welfare Department. In schools, the Education Bureau supports students through grants.

“Support and services should not come only after tragedies. They should accompany people’s development,” said lawmaker Shiu Ka-chun, who represents the city’s social welfare sector. He has joined the association to appeal for resources.

Families with special-needs children said they had been struggling with the instability and hefty cost of support services.

Hong Kong’s school system shuts out non-Chinese-speaking special needs children

A mother who only wished to be known as Suen said her family had to spend HK$3,200 a month for eight sessions on attention and social skills training for her seven-year-old son. It posed a “heavy burden”, she said.

Her son, who was diagnosed with developmental delays and ADHD, always failed to submit his homework on Fridays because he was exhausted by the sessions every Thursday, she added.

“It has been difficult for him. It has been difficult for me. But we have to keep it up because there is little support at his school,” Suen said.

Another mother who called herself Fung said she had to seek support from a social worker because she had not been able to find any rehabilitation services for her seven-year-old since the boy began refusing to go to school last October.

Diagnosed with dyslexia and ADHD, the child had told Fung he was often scolded by his teachers and asked to stand outside the classroom because he could not sit still like his classmates.

“I gave his assessment reports to the school and explained this to his teachers, but they always told us to transfer him to another school,” Fung said.

With the family’s consent, the boy was suspended from the school in March.

“I don’t know what kind of training he needs. I don’t know where to find him the right training centre,” Fung said, in tears. “Sometimes, I just want to give up.”

A spokesman for the Social Welfare Department said child users of preschool rehabilitation services may continue to receive necessary support under the education and healthcare system after leaving the service at the age of six. “[The department] is discussing with the Education Bureau on how to strengthen the connection between preschool rehabilitation service institutions and ordinary primary schools,” the spokesman said.

In 2018/19, the government would provide 439 additional preschool rehabilitation places, including 258 places at special child care centres and 181 at early education and training centres, according to the spokesman. It also planned to set up 13 parents resource centres, in addition to the existing six centres, to meet the growing demand for from parents and carers.