Why don’t Hong Kong Canadians just say they are Chinese? Because of subethnicity, and this is why it matters

- A study of ethnic Chinese in Vancouver points to the wide gaps between Hongkongers and mainlanders, defying assumptions about ‘Chinese Canadian’ homogeneity

- Politics, language, and battles over ‘cultural authenticity’ serve as dividing lines – but some friendships manage to bridge the subethnic gap

Hong Kong people come from a colony and ought to act “more civilised”. Taiwanese are “old-fashioned”. Mainland Chinese are “rich but rude”.

Welcome to the awkward world of Chinese subethnicity in Canada, where its various communities tend to self-segregate, discriminate against each other and generally defy assumptions of homogeneity among “Chinese Canadians” that are imposed from outside the group.

Subethnicity among Vancouver’s ethnic Chinese is the subject of new research by academics Miu Chung Yan, Karen Lok Yi Wong and Daniel Lai. It focuses on the wide gaps between Vancouver’s mainland Chinese and Hong Kong communities, drawn on lines of language, geography, culture and politics.

“The influence of transnational politics on interpersonal interactions at the individual level cannot be underestimated,” the study concludes, with political conversation “taboo” between the groups. “Avoidance is a major strategy,” says the study, published last month in the journal Asian Ethnicity.

Professor Yan, the director of the social work department at the University of British Columbia (UBC), spent four years studying subethnicity for the project.

Some of the results were “common sense among Chinese”, he said, but might surprise others. People in the Chinese subethnicities tend to stick to their own kind when making friends. Language can divide them.

And when relatively uncommon friendships do emerge across the subethnic boundaries, they usually happen in non-Chinese environments, where a Hongkonger and a mainland immigrant might find common ground as outsiders.

China is the real power, so they have pride over here [in Vancouver]. In interaction with people from Hong Kong, they feel ‘Why should everything be Hong Kong? Why should I go to a Hong Kong seafood restaurant? Why should we have a supermarket where they only speak Cantonese?’

“We [ethnic Chinese] all know about the gaps and tensions between Chinese from different places,” Yan said when asked about the study, which involved dozens of ethnic Chinese Vancouverites, mostly mainlanders and Hongkongers, as well as a small number of Taiwanese immigrants.

“But the majority of Canadians look at us all as one group [and] that’s not the reality.”

He said the tendency of Hong Kong-origin people to now identify as Hongkongers or Hong Kong Canadians – and not simply as Chinese, or Chinese Canadians – had solidified since the 1997 handover.

Thousands of Hong Kong-born people are returning to Canada

That tendency is even more extreme among young people: in 2017, Hong Kong University pollsters found that only 3.1 per cent of respondents in Hong Kong aged 18-29 identified as Chinese, compared with 65 per cent who identified as Hongkongers.

The world has recently been getting a crash course in Hong Kong identity, via massive marches against a proposed law that would allow the extradition of suspects to mainland China.

Amid the cries for leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor to step down, the most common chant was a simple invocation of local identity: “Heung Gong Yan [Hongkongers]! Ga yau [add oil]!”. “Add oil” is a ubiquitous Cantonese cry of encouragement or persistence: keep going, you can do it.

Boston student wrote ‘I am from Hong Kong, not China.’ Then trouble began

Such tendencies about identity – and the associated tensions – flow on to diaspora communities like Vancouver, and elsewhere.

The phenomenon garnered headlines in April, when Frances Hui, a Hong Kong student at Boston’s Emerson College, wrote a column titled “I am from Hong Kong, not China” for Emerson’s student paper. A strong backlash from mainland Chinese students ensued.

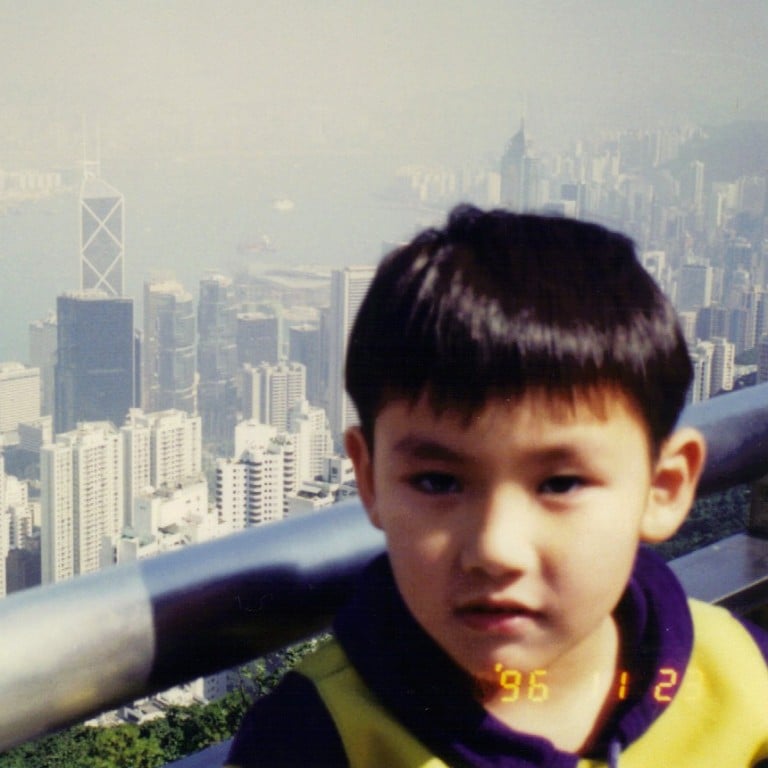

“Before 1997, [Hong Kong] people were more open to identifying themselves as Chinese, at least when I grew up in Hong Kong,” said Yan, who emigrated to Canada in 1993.

“We’d say ‘I’m Chinese’. We didn’t call ourselves Hongkongers. But 1997 is definitely the dividing line, mainly because of the influx of mainland Chinese [to Vancouver].

“They speak a different language, they come from a different background. There became more and more need to differentiate ‘us and them’.”

'Hongers' and their place in the subethnic landscape

Marketing professional Simon Tse moved from Hong Kong to Vancouver in 2006 as a teenager. But he has been a Canadian citizen since birth, born in Hong Kong to immigrant parents who were naturalised in Canada and then returned to their home city.

Now 29, he calls himself a “Honger” (a common designation among the North American diaspora), “Hong Kong Canadian” or simply “Canadian”. But Chinese Canadian? Not so much.

Vancouver’s ‘Cantosphere’ and the fate of Hong Kong

“We’re all living in Canada now, right? But for my own identity though, I still insist that I be called a Hong Kong Canadian rather than a Chinese Canadian,” he said.

“At the end of the day, I can’t get away from the fact that Hong Kong is my birthplace. I spent 16 years growing up there. What happens there is still of great importance to me.”

The fact that other Canadians might not understand the differences meant Tse “felt the need to clarify my own identity to those who asked – not only because of my fairly complex status as a second-generation Canadian, but to explain my own Westernised upbringing that other subethnic groups may not have experienced.”

Tse said the non-Chinese friend in Vancouver who understood his identity most came from Quebec, the French-speaking Canadian province that has long grappled with identity.

At the end of the day, I can’t get away from the fact that Hong Kong is my birthplace. I spent 16 years growing up there. What happens there is still of great importance to me

Yan said navigating the subethnic Chinese landscape was challenging for an outsider. “I would say the No 1 thing to know is that being ‘Chinese’ is not homogenous,” Yan said.

“And what about the ‘old overseas Chinese’, loh hua qiao [lo wah kiu in Cantonese], who have been here for two or three generations? They don’t like Hong Kong Chinese. They don’t like the new mainland Chinese. The differences are not just about from where you came. It’s when you came.”

And frequently, this boiled down to class.

Just as some middle-class Hongkongers resented the recent influx of wealthy mainlanders to Vancouver, and their impact on affordability in the city, the less well-off lo wah kiu (a “sub-sub-ethnicity” said Yan) resented rich Hongkongers buying up expensive homes in the 1990s.

Property agent Abraham Wong, 32, moved to Canada with his family on July 3, 2003, two days after a massive protest in Hong Kong against proposed national security laws. It was a key event in the forging of a newly assertive Hong Kong identity. Wong was 16 at the time.

“I’m a Hongkonger, a Hong Kong Canadian, not Chinese. In Hong Kong I call myself a Hongkonger. Here, in Canada, in a Chinese group, I call myself a Hongkonger,” he said.

“Vancouver is a strange place. Some Hongkongers don’t mind being called Chinese. But my personal point of view [is] that Hong Kong people strongly prefer to be called Hong Kong Canadian.”

It is a matter of culture, Wong said. “‘Hongkonger’ or ‘Hong Kong Canadian’ is an expansion of how we live, how we eat, what kind of home we grew up in.”

Has Hong Kong failed? From Vancouver, it can look that way

But Wong said he has found himself being referred to as “Chinese” in Vancouver “all day long”, describing “Chinese Canadian” as a “politically accepted term” used by the non-Chinese community.

Yan’s study said that cultural differences among the various groups had led to a “competition for cultural authenticity” in Canada.

But a counterprotest group swiftly emerged to support the facility, arguing that Chinese culture respected the processes of death and dying. The counterprotesters were mainly Hong Kong immigrants.

“This kind of competition challenges the assumption of homogeneity and solidarity within an ethnic group,” the study concludes.

In the Vancouver context, language emerged as a key source of conflict – specifically, Cantonese-speaking Hong Kong respondents in the study complained about negative experiences in Chinese supermarkets, now increasingly staffed by Mandarin speakers.

Don’t politicise Hong Kong people’s fluid identity

This kind of daily friction, reinforcing prejudices on both sides, reflected demographic realities – in metro Vancouver, people born in mainland China now easily outnumber people born in Hong Kong, by 188,865 to 71,720 according to the 2016 census (with 37,425 born in Taiwan).

And Mandarin is on the brink of replacing Cantonese as the most prevalent non-English mother tongue in the city.

When it comes to Vancouver’s subethnicities, “size matters”, said Yan.

“Mainland Chinese became the No 1 incoming group. Where do they go? Where the Hong Kong people used to be. They start taking up the restaurants, the grocery stores … You go to T&T [a Chinese supermarket chain] now, and if you speak Cantonese you get asked ‘Why don’t you speak Mandarin?’”.

“That’s a tension. That makes the label ‘Hongkonger’ more substantial. Who we are, who we are not.”

Yan said he had seen the segmentation along the lines of language play out in microcosm at parties. “Those who speak Cantonese all gather together … The community is just a bigger manifestation of the party.”

Similarly, mainland Chinese in Vancouver differentiate themselves from Hong Kong people because “they see mainland China as a growing superpower, and Hong Kong is shrinking, economically, culturally”.

Changes that were sore points for Hongkongers in Vancouver made perfect sense from a mainland Chinese point of view. “China is the real power, so they have pride over here,” said Yan.

“In interaction with people from Hong Kong, they feel ‘Why should everything be Hong Kong? Why should I go to a Hong Kong seafood restaurant? Why should we have a supermarket where they only speak Cantonese?’”

Crude stereotypes and bridging the gap

Amid these divisions, members of Vancouver’s Chinese subethnicities sometimes fall back on rather crude stereotypes of each other.

These were summarised by Hongkonger Myles, one of the subjects in Yan’s study. “Taiwanese think that Hong Kong (Chinese) come from a British colony. They think Hong Kong people should be more advanced, more civilised …

“Hong Kong people see Taiwanese as old-fashioned, but they feel that they are easy to interact with. Probably because most of the people who have arrived recently [from Mainland China] are very rich but rude, [Hongkongers] find it difficult to get along with them.”

The mutual bias between Hong Kong and mainland Chinese “is common knowledge”, the study says.

But Yan said there was room for optimism that such gaps could be bridged. The study cites five pairs of friends who managed to overcome the subethnic divide, although Yan said finding them wasn’t easy.

One way or the other, we are put being together … [we] are all being seen as ‘Chinese’ and you have to live with that

Proximity was the main facilitator: these subjects mainly worked together, and in a non-Chinese-majority environment.

“In their situation, in a non-Chinese context, who understands you better? The non-Chinese? Or the other Chinese, even if you don’t speak the same language?” said Yan.

And ironically, it was a flawed assumption by other Canadians – that all Chinese were alike – that sometimes served to bring people together.

“One way or the other, we are being put together … [we] are all being seen as ‘Chinese’ and you have to live with that. If we don’t come together, our situation might be worse,” Yan said.

There was a kind of “reluctant optimism” behind such friendships, he said.

“How do we turn this into a positive energy, to help more people come together? That’s something we should consider.”