Video | How a struggling Chinese student ‘sold himself’ to attend dream US school

When traditional institutes refused him a loan, Deng Linjie turned to Chinese social media for help, vowing to return money he took with 20 per cent interest

Fortune seemed to smile on Deng Linjie when he learned he had been accepted into an elite US art graduate school.

He had grown up with little money for luxuries. Just about the only thing in abundance in his North China home as he matured into a young man had been the sound of his parents quarrelling before they separated.

To someone who had only known two cities – Linfen, his hometown in southern Shanxi province, and Beijing, where he had gone for his undergraduate study – the offer of admission from the prestigious School for Visual Arts in New York City was a dream come true.

But Deng faced a tough struggle finding a way to pay for his anticipated education expenses.

His undergraduate institution, Beijing City University, had refused to help him when he explained to officials that his family had just 200,000 yuan (US$31,036) to spend on his education in New York. Tuition for the Master of Fine Arts programme at the School for Visual Arts was 700,000 yuan (US$108,626).

Deng’s mother had raised the money on her own to pay for his Beijing studies after separating from Deng’s father.

When Deng applied to the Bank of China for a student loan, he was told that his undergraduate degree from Beijing City University simply was not regarded highly enough to warrant the bank’s offering him a loan.

After the governments of Beijing and Linfen also declined to lend Deng money, he was desperate. Before setting up his new base in the US, he turned to an unorthodox source for help: the denizens of China’s social media networks.

Logging into WeChat, the popular mobile messaging, social media and payments platform run by Tencent Holdings, and weibo, the Chinese-language microblog loosely modelled on Twitter, Deng made a bold offer.

He promised that he would repay any offers of financial aid in just over two and a half years – or by the end of 2017 – and at 20 per cent interest.

He posted the terms of a contract he drafted on his personal weibo and WeChat accounts and asked friends to share it.

Something in Deng’s offer touched people’s hearts at the other end of his earnest, yet businesslike, plea for help. Within a week, he received the 500,000 yuan he needed to fund his education.

The dream had become reality.

“I wasted a whole month searching for help from those [traditional lending] places,” Deng told the South China Morning Post in an interview.

“I finally came to the idea of crowdfunding. ‘Why don’t I just sell myself?’, I thought.

“The government gave up on my university, and my university gave up on me. But I can’t give up on myself.”

By May 2017, Deng finally had his degree in hand. But the list of jobs and other activities the 25-year-old took on – or has continued to take on – to repay his debts is certainly impressive.

For two years, he lived in a church in the New York borough of Brooklyn to save money.

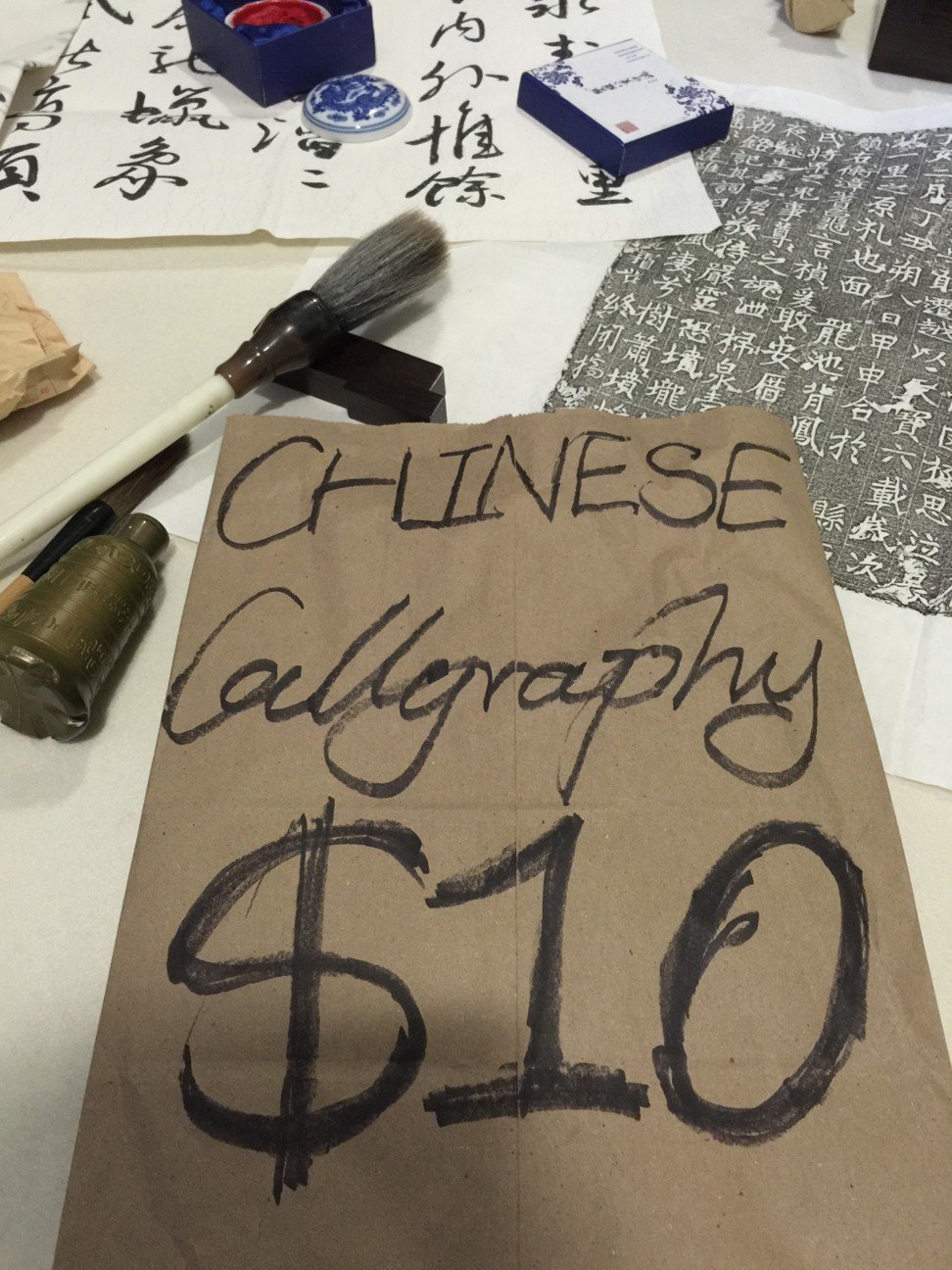

Besides holding down a part-time job at his school library, which gives international students 20 hours of on-campus employment a week, he is a New York street vendor, selling his Chinese calligraphy to tourists, businesspeople and other passers-by.

His education-related enterprises have included teaching design for social innovation, his major in school, to Chinese students online on weekends.

He also has helped Chinese students develop US university applications and has designed websites for companies.

Leaving no potential revenue-generating resource untapped, he even sold his sperm to a US sperm bank.

“I was like falling into a coin hole the moment I landed in New York,” Deng told the Post.

But he has paid back most of his debt on time. He said he has about 20,000 yuan left to pay to more than 40 people with whom he has lost contact since they agreed to lend him money, he said.

To keep his creditors’ confidence, Deng has updated them via weibo and WeChat regularly on where the money has gone and how he has done academically at school.

His success at tapping the promise of the internet for fundraising contrasts with the plight of many Chinese students who have been forced to give up a dream of overseas study owing to insufficient financial resources.

Deng is not the only Chinese student to attempt to crowdfund his tuition costs amid the rapid evolution of mobile finance.

Such students typically launch invitations on social media platforms, arranging to receive payment directly on WeChat or other mobile apps tied to bank accounts.

But not all have successfully raised the money sought, owing to widespread scepticism about whether such requests are legitimate or even needed.

Wu Jundong, a graduate from Renmin University of China who was offered admission in Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government in 2015, ignited controversy after receiving 50,000 yuan in crowdfunding to ease his family’s financial burden.

Whereas Deng had vowed to repay his loans, Wu had promised to reward donors by sharing online his takeaways from his studies and his US experience. Many found that promise hard to value. The offer made headlines before eventually fading from view.

Emma Peng, a Chinese student at the University of Florida who frequently posts beauty-related videos on YouTube, withdrew an appeal she had made to viewers to lend her 50,000 yuan in July 2017 after users questioned her need for the online outreach and said they doubted she had tried other ways to raise money.

The student had said she could not pay her 100,000 yuan tuition for the following semester because of an unfortunate event in her family. She posted bank accounts in the video, without mentioning any form of reward.

Her critics accused her of begging for money – and making no effort to explore options such as taking a one-year hiatus from academic studies until she straightened out her finances.

Deng, by contrast, said he turned to crowdfunding only after exhausting all other options for financial aid.

Although Deng met his fundraising goal quickly, he said he endured attacks and criticism along the way.

“I talk to the media now because first, I want to find those helpers who have lost contact,” he said. “Second, I want to tell people that I’m not a liar, to let those who have attacked me shut up. Honesty is not something related to age, or generation,” he said.

Zheng Huaide, a project manager at Venco, a Shenzhen-based company which designs and operates crowdfunding projects, said the kind of appeal that Deng and other students launch is akin to asking for a charitable donation, combining social networks with a public perception of the student’s personal credibility.

“It’s an individual practice and there’s no business model in this regard on the mainland so far,” Zheng said. “The risk [for the donors] is high, which explains why there is so much scepticism.” Donors also can lose track of a loan once the student goes abroad, Zheng said.

Beijing-based philanthropy expert Zhang Gaorong said the emergence of crowdfunding as a potentially viable funding avenue points to how Chinese society is “governing itself through a new way”, providing people with a different path for realising dreams.

“In nature, it is borrowing money without a mortgage,” said Zhang, a former assistant director at the China Philanthropy Research Institute who now is pursuing a sociology PhD at Peking University.

“In the past we borrowed money from familiar people, and now with the development of the internet, we are able to borrow it from strangers.

“When a society diversifies, it gives space for new things,” Zhang said. “People have more channels to reach what they aim for.”

Deng’s method of funding his tuition would draw either praise or criticism, depending on the extent to which he had successfully created credibility with individual potential lenders, Zhang said.

“If you trust the launcher, you give the money. If you don’t, it’s fine.

“We may have not reached the stage of high credibility, but I think trust can be built gradually,” Zhang said.

Tian Xue, who did not know Deng when she lent him 10,000 yuan, said she never doubted the student would be good for the loan.

“I thought it must be a very important opportunity for him,” said the Shandong woman who has become good friends with Deng. “I thought that he must be a man of his word and that he must yearn for this opportunity very much when I saw him offering the 20 per cent interest and art guidance in the future as a reward.”

Deng repaid her bit by bit, in 12 sums, Tian said.

“Every time he repaid a sum, I knew it was not easy for him to live in New York … The next year he repaid all the money, plus interest. I was so surprised. He was just so hard-working.”

Alvin Sun, a friend of Deng’s from Beijing City University who offered to lend him 1,000 yuan, said she believed Deng would pay off his debt because “he is the kind of person who acts on what he says”.

“When he gave the money [back] to me, I thought, if I don’t accept it, he’d always feel that he owes me. So I took it, finally.”

And if Deng ever needed a loan again? “I’m still willing to help him,” Sun said.

Although Deng has graduated, he said he has continued doing various jobs to make ends meet.

“My priority now is not a full-time job, but making money,” he said.

His plan is to return to China in a few years. In the meantime he plans to team up with a New York artist on a public art project.

When Chinese New Year celebrations roll around next month, Deng said he will have to miss his native country’s most important family gathering festival.

“You know I just passed the deadline for repaying my debt,” he said with a laugh. “Now I have no money for plane tickets.”