Does the ghost of a conflict lie at the bottom of a Tibetan lake?

- Chinese researchers say sediment samples may show signs of a battle with the British army in the area more than a century ago

- ‘Unusual’ spikes in the presence of certain metals may point the use of modern weapons but more study needed, they say

But two spikes in the presence of metals in two sample sections dating to the 1880s and 1900s caught their attention.

The sediments indicated that various metals, including chromium, nickel and zinc, had been released into the atmosphere at the time, fell on the glacier and eventually ended up on the bottom of the lake.

“This is quite unusual,” said Wang, a researcher with the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing.

Levels of the metals in the other parts of the samples were consistently low and the researchers were unable to find similar increases in the same periods in cores taken in other parts of the world.

“It is not a 100 per cent verdict, but the most reasonable explanation we can find is the wars,” Wang said in findings published in peer-reviewed journal Environmental Science & Technology last month.

The researcher was referring to two “expeditions” into Tibet by the British army in colonial India in the 1880s and 1900s.

The conflicts set the British, armed with rifles and artillery, against Tibetans, who were equipped with swords and antiquated muskets.

There were wins and losses on both sides during the first encounter. But the Maxim machine gun used by the British in the second “campaign” in 1904 was decisive, killing about 3,000 Tibetans by some estimates.

“They poured a withering fire into the enemy, which, with the quick-firing Maxims, mowed down the Tibetans in a few minutes with a terrific slaughter,” Austine Waddell, a British army doctor, was quoted as saying in Duel in the Snows, written by Charles Allen.

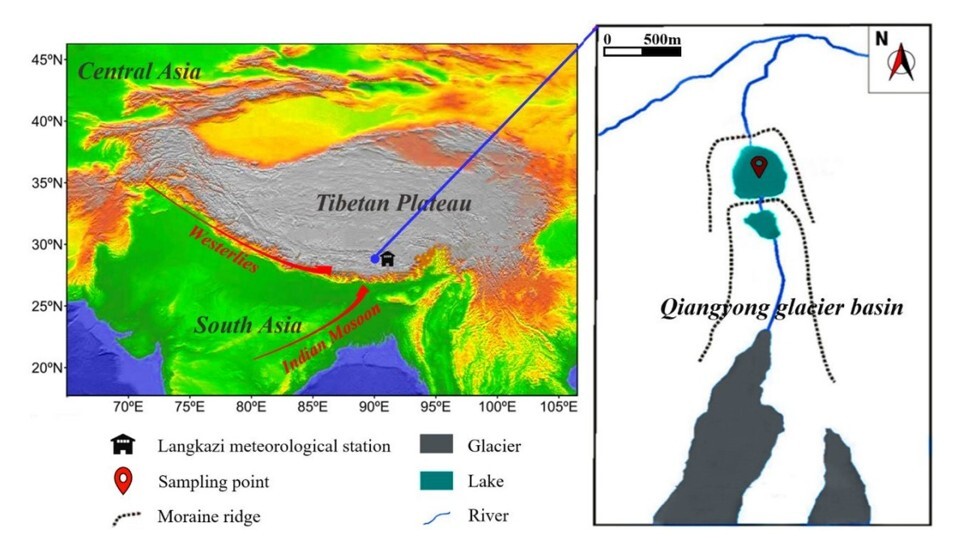

But did the British battle the Tibetans at or near Qiangyong lake?

Local folklore does refer to resistance to Western invaders across southern Tibet but “no written records have been preserved in this remote area”, Wang said.

Chromium, nickel and zinc are used to strengthen steel and prevent rust. Though detailed composition of metals that make up the British weapons in Tibet remained unclear, they have been widely used as coatings for gun and artillery barrels.

Wang said that if the metals in the lake samples did come from the Maxim or other weapons used by the British army, more data would be needed to answer questions such as how many guns were used.

The study is far from finished, and “we need samples from other lakes nearby to verify these findings”, Wang said.

Wang said the trace elements in the Qiangyong core also showed signs of other human activities, including the second world war and the rapid industrialisation in China and India. In addition, global climate change had accelerated the build-up of sediment at the lake’s bottom, she said.