Wuhan lab coronavirus conspiracy theories shine spotlight on super-secure facilities

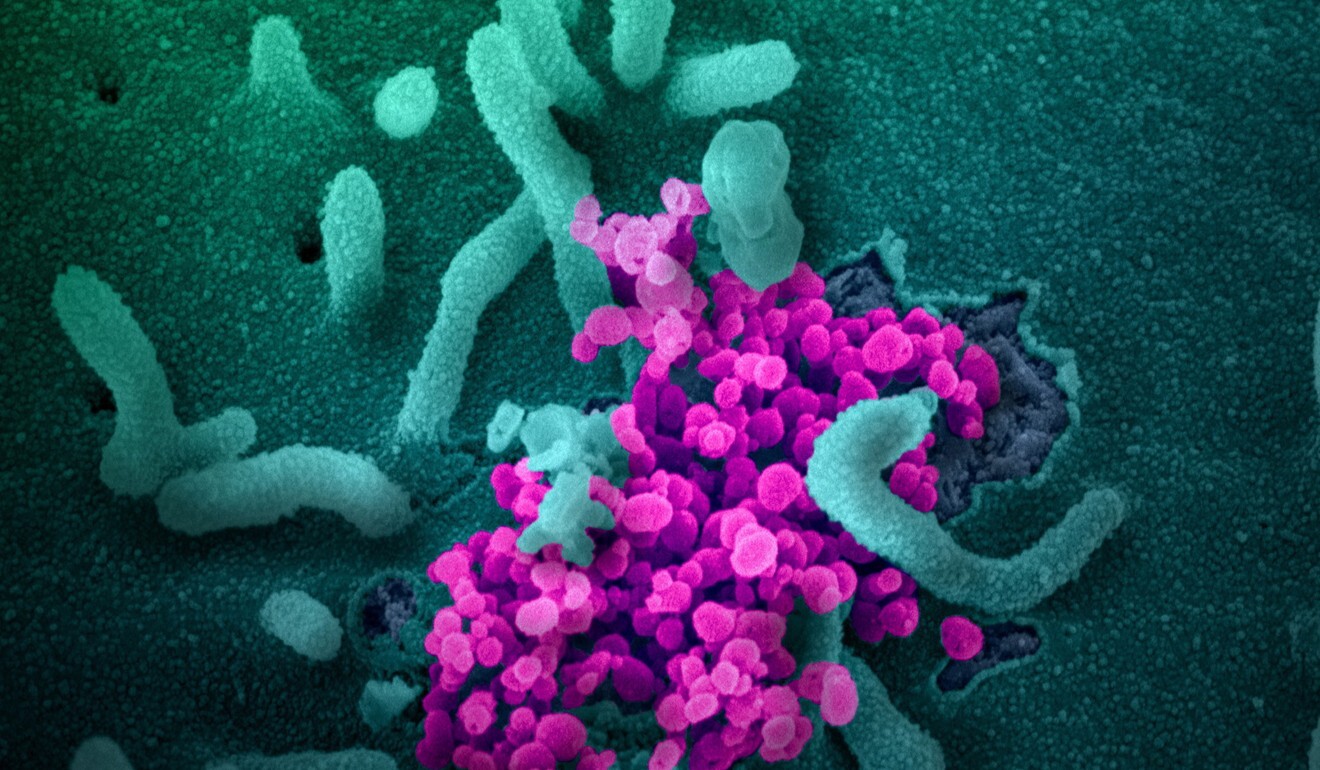

- The Wuhan Institute of Virology has been at the centre of a number of Covid-19 conspiracy theories, including one that the virus accidentally escaped

- The facility has the highest possible levels of security to stop deadly pathogens escaping and accidents are rare in such labs

While human error can never be entirely eliminated, such accidents are extremely rare and those familiar with working in this environment have explained that researchers working in them are subjected to a number of strict checks and controls.

But while some Hollywood movies and the video game Resident Evil have popularised the idea of pathogens being accidentally released, scientists say it is unlikely that this could happen in labs that are designed to contain deadly pathogens and must be certified to meet the highest safety standards.

Coronavirus: Wuhan lab at centre of conspiracy theory targeted by hackers

The institute has been approved to study the most deadly pathogens such as Ebola, West African Lassa virus and Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever viruses. Other less lethal pathogens are also studied in lower-security facilities.

Yuan Zhiming, director of the laboratory, had denied that it had any role in the outbreak and other scientists and the World Health Organisation have repeatedly debunked the suggestion that the virus, officially known as Sars-CoV-2, had been genetically engineered in a lab.

“Experiments that take half an hour in other labs would take three hours in a BSL-4 lab,” researcher Shi Zhengli told Hubei Daily in 2015 after construction work on the Wuhan facility finished.

“You might need to pass through several doors to fetch something from the refrigerator. It’s a very complicated process but it must be done [that way].”

A researcher who runs a university-affiliated BSL-3 lab, speaking on condition of anonymity, said labs had strict protocols to ensure biosafety.

The researcher said animals used in experiments in these facilities underwent high-pressure sterilisation before being disposed of and all waste material was processed in the lab.

All those entering or leaving the facility had to have their body temperature taken and researchers’ blood was regularly taken for checks. Staff activities were also recorded and saved as part of the safety protocols.

“I have never been to a BSL-4 lab but the protocols and security will be higher than at a level 3 lab,” the researcher said.

Coronavirus: Wuhan virology lab’s long history of scientific collaboration

Generally, scientists who enter such labs wear full-body biosafety suits, on top of two layers of protective clothing, and they have their own oxygen supply so they do not breathe the air inside the lab.

The facility uses negative air pressure and airlocked doors to stop contaminated air leaking out, and researchers must go through chemical showers when leaving and undergo strict entry and exit procedures.

The lab air is filtered and waste water processed before being discharged.

Researchers also need to be trained in safety protocols before being allowed to work in such high containment facilities.

But scientists concede that accidental releases or lab-acquired infections have happened, usually as a result of human error.

In 2004, a doctoral student took a live severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) virus that she believed to be inactive from a BSL-3 lab at the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention to be studied in a lower-level facility. The incident resulted in nine people being infected, one of whom died.

A year earlier, a 27-year-old doctoral student in Singapore became infected with Sars at a government-run facility because of what the WHO later described as “inappropriate laboratory standards and cross-contamination of West Nile virus samples with Sars coronavirus”.

In Britain, a 2007 outbreak of foot-and-mouth, a highly contagious livestock disease, was traced to leaks from a drainage pipe at the BSL-4 lab in the Pirbright Institute, an animal-health research centre.

The US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention reported in December 2014 that samples containing live Ebola virus had been transported from a BSL-4 lab to a BSL-2 lab, where such deadly pathogens were not allowed.

Coronavirus: the Wuhan lab conspiracy theory that will not go away

Richard Ebright, a molecular biologist at Rutgers University in New Jersey and laboratory director at the Waksman Institute of Microbiology, said: “Laboratory accidents – especially laboratory-acquired infections – are common. This is true worldwide.

“Laboratory accidents almost always involve human error, even the best-designed and best-constructed biocontainment laboratories cannot prevent human error.”

Filippa Lentzos, from the department of global health and social medicine at King’s College London, said there had been a big increase in the number of high containment labs being built “over the last decade or so”.

“While these are good for learning about viruses and bacteria and the etiology of diseases, they come with a trade-off for safety, security and responsible science,” Lentzos said.

An international survey published in the European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases in 2016 found that while laboratory-acquired infections from level 3 and 4 facilities remained rare, human error was responsible for a high proportion of the cases.

Data from the US Federal Select Agent Programme and from the National Institutes of Health also found human error was the main cause of potential exposures of lab workers to pathogens, accounting for 79 per cent of cases between 2009 and 2015 and 67 per cent of cases between 2004 and 2017.

Lynn Klotz, a senior science fellow at the Centre for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation who obtained the data through the US Freedom of Information Act, said none of the accidents involved BSL-4 labs.

According to his report, many of the accidents were one-offs that were unlikely to happen again.

“One example was a misplaced tool causing half the liquid in a plate to spill onto a bench top,” the report said. “For some errors, there are procedural changes that should reduce their frequency.”

Lentzos said safety lapses related to risk assessments were also a concern.

“The lapses I’d be most concerned about relate to containment, essentially making sure standard lab safety practices are adhered to, including lab waste disposal practices and infection reporting,” she said.