China’s Inner Mongolia emerges as model for Xi Jinping’s ethnic affairs policy, but analysts warn of cultural ‘erosion’

- The autonomous region trumpets its success in assimilating minority groups to promote national identity through language, censorship and local laws

- The policies do not attract as much criticism as those in Tibet or Xinjiang and are likely to be rolled out in other autonomous regions, analysts say

A decade after President Xi Jinping called for “a strong sense of community for the Chinese nation” as the cornerstone of his ethnic affairs policy, the Inner Mongolia autonomous region has emerged as a model for implementing the leader’s vision.

While Inner Mongolia has trumpeted its success, analysts have raised concerns that the policies could weaken the identity of ethnic minority groups. They say the region’s policies are a sign of things to come for China’s other autonomous regions.

According to the 2020 national census, the combined population of China’s 55 ethnic minority groups totalled 125 million, accounting for about 8.9 per cent of the country’s population.

Ethnic tensions, especially in Xinjiang and Tibet, have posed a challenge for Beijing. Frequent violent attacks in Xinjiang, followed by Beijing’s controversial control measures in the restive region starting in 2016, have led to accusations of suppression and human rights abuses, which it has denied.

Of China’s five autonomous regions, Inner Mongolia has the smallest proportion of ethnic minorities, accounting for about 21 per cent of its population of 24 million.

Ma Haiyun, an associate professor of history at Frostburg State University in Maryland, said that Inner Mongolia’s relatively small ethnic minority population meant it might not attract as much international attention as Tibet or Xinjiang, so the policies implemented in the region “may face minimum international criticism”.

Ma noted that Inner Mongolia has long been a pioneer and test bed for China’s management of ethnic affairs. The Communist Party established effective control and autonomy in Inner Mongolia in 1947 – two years before the founding of the People’s Republic of China – and ever since it has been considered the model for ethnic autonomy.

Xi first put forward the concept of “a sense of community of the Chinese nation” in 2014, signalling the start of the new ethnic affairs policy. At a 2021 meeting, he said forging this sense of community should be at the centre of all ethnic minority policies, prompting more proactive measures by local authorities.

The decision orders Inner Mongolia’s authorities to educate locals to “be grateful to the party and to General Secretary Xi Jinping” and requires the region to become a model for “forging a strong sense of community of the Chinese nation”, and that all work in the region must be centred on that theme.

At the end of December, local authorities issued a comprehensive guideline requiring government departments at all levels and in all regions to incorporate a “sense of Chinese national community” into their work plans, adding that implementation would be among the criteria for assessing officials.

The guideline also requires the region to continue to crack down on “subversion by hostile forces” and “deal with cases and incidents involving ethnic factors appropriately”.

In late December, Inner Mongolia’s ethnic affairs committee said in an online article that the region’s universities were the first in the country to offer a mandatory course on the “sense of community of the Chinese nation”.

James Leibold, a specialist in China’s ethnic politics and a professor at Melbourne’s La Trobe University, said Inner Mongolia was “at the forefront of Xi’s nation-building agenda” and expected similar measures to be “gradually rolled out across other minority regions”.

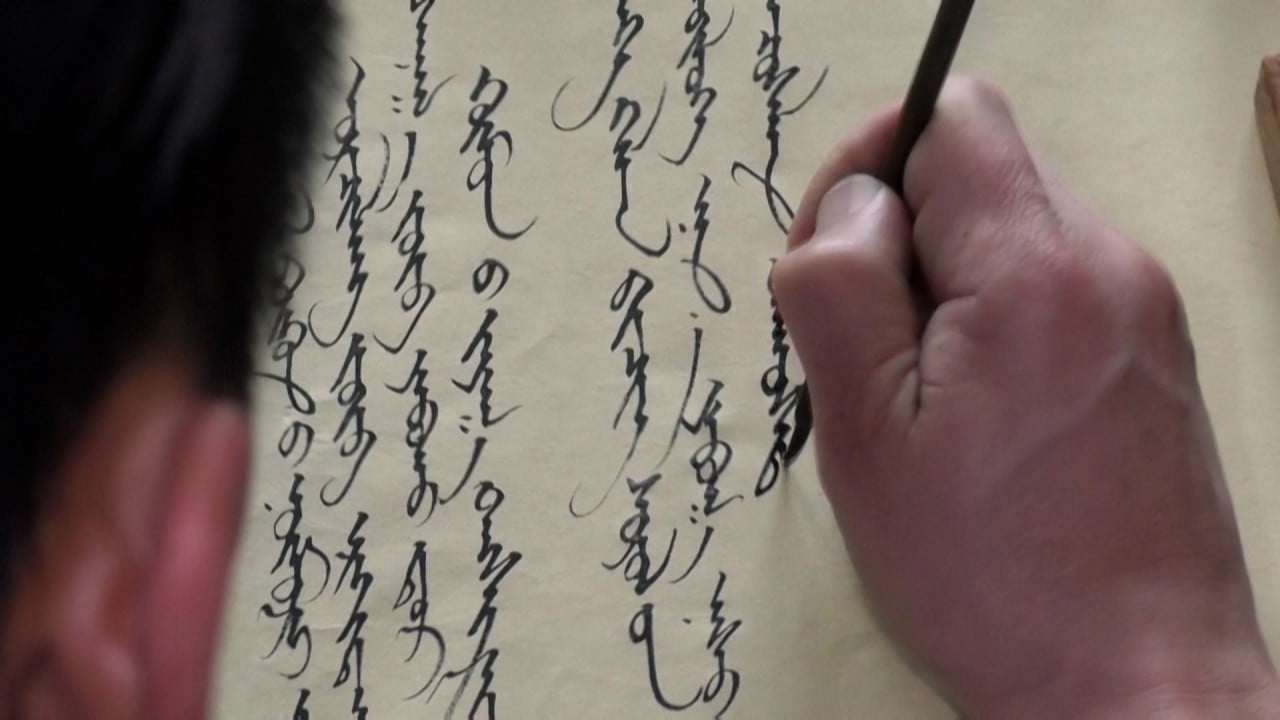

He voiced concerns that “these new policies continue the gradual erosion of minority languages, cultures and identities”.

Shi held the post from 2019 to 2022. He is now head of the United Front Work Department – the top official in charge of ethnic affairs – and a member of the Politburo, the party’s elite 24-member decision-making body.

Shan said Shi’s ties to Inner Mongolia might have led to the region “taking the lead in some of the ethnic policy experiments”.

June Teufel Dreyer, a political scientist at the University of Miami, described the moves in Inner Mongolia as “assimilationist policies”, and said they were the latest in “a gradual, low profile incremental expansion of restrictions”.

Barry Sautman, professor emeritus at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, said the new ethnic policies introduced by the Chinese leadership “aim to bring about a higher level of interaction among ethnic groups, including in residential areas, workplaces and other areas.”