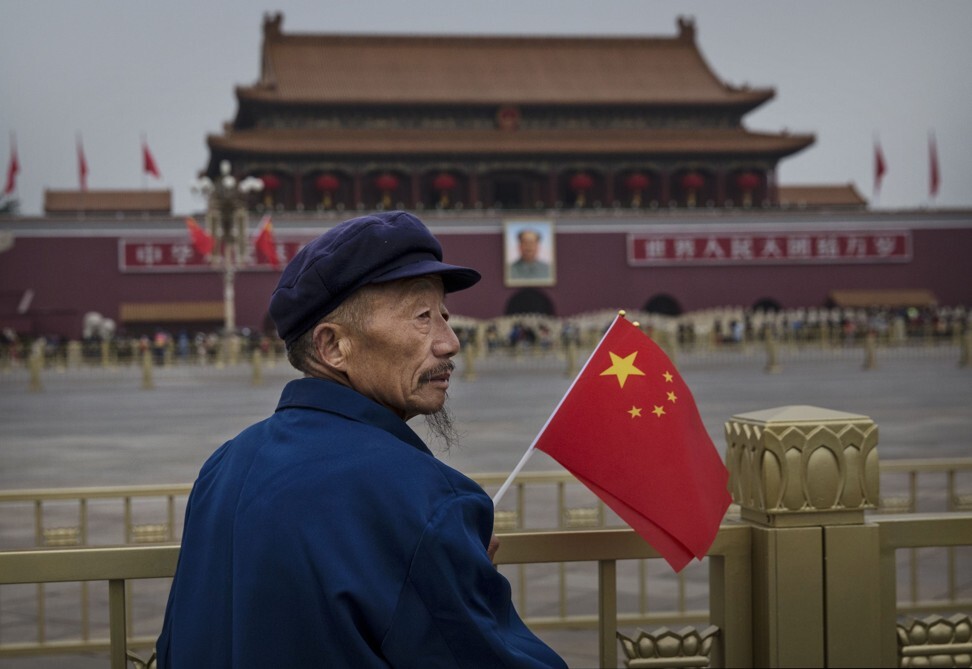

The age of uncertainty looming for China’s future retirees

- Census figures confirm that the country is greying rapidly and the pool of people paying into pensions is shrinking fast

- The generation gap leaves workers wondering what lies ahead

This is the 16th in a series of stories about China’s once-a-decade census, which was conducted in 2020. The world’s most populous nation released its national demographic data in May and the figures will have far-reaching social policy and economic implications.

Gu Qunzhen, 69, started her day by bargaining with vendors at a suburban wet market in the northern Chinese municipality of Tianjin.

She spent around 10 yuan (US$1.57) on cabbage, cucumbers and tofu and went home to prepare the day’s meal for herself and her 75-year-old husband.

Gu gets around despite the blurred vision caused by cataracts. The condition is easily treatable with surgery but she has decided against the operation, at least for now.

“It’s all right. I can still see things,” Gu, a former accountant, said. “We retirees should live frugally and try to avoid medical bills.

“I’m saving for my sons and grandchildren. When they grow old, it may be harder for them to lead a quality life.”

That is because there will be fewer people to pay into the social welfare system and keep the benefit schemes afloat.

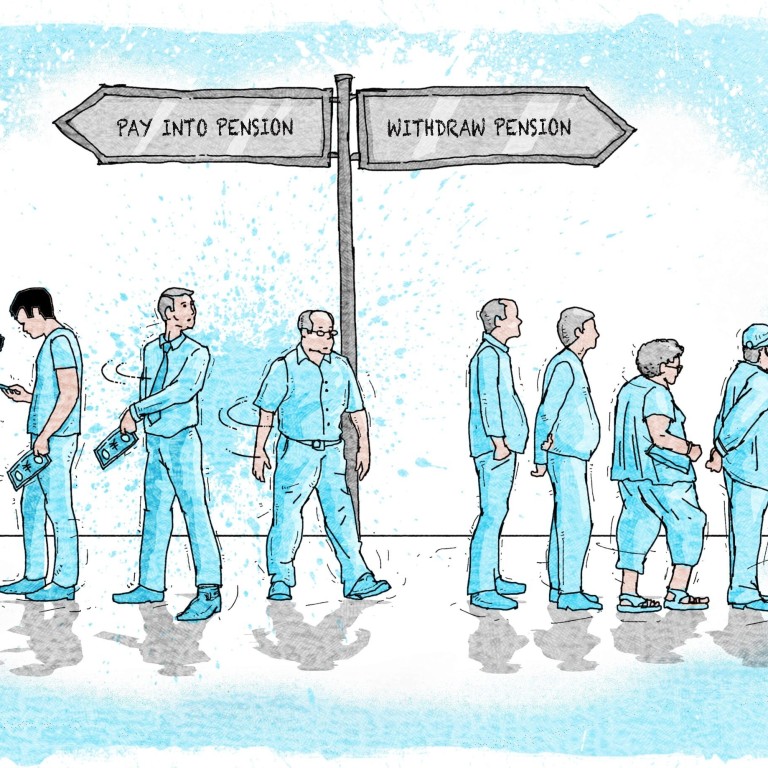

The census showed that China’s working age population between 15 and 59 fell to 894 million, down about 5 per cent from a 2011 peak of 925 million. While the number of workers contributing to the pension fund declined last year, the number of people aged 65 and over increased to 191 million in 2020 from 119 million in 2010.

It all means that 13.5 per cent of the population relied on the fund in 2020, up from 8.9 per cent a decade earlier.

China’s pension replacement rate, indicating the levels of pension benefits in retirement relative to earnings when working, has also fallen over the decades.

While retirees’ pensions were equivalent to 87 per cent of employees’ average salary at the year of retirement in 1998, the proportion has fallen all the way to around 45 per cent in recent years, according to a CASS report released last year, suggesting a substantial decline in living standards for the retirees.

China needs to give incentives for couples to have a third child, analysts say

Zhang Cheng, a 45-year-old marketing manager at an internet company in Beijing, said he was shocked to realise that life after retirement would not be as he imagined.

“The census is like a wake-up call. I thought I would be able to continue with the middle-class lifestyle after retirement – going to the theatre, camping with friends on weekends, driving around China and spending overseas holidays with my daughter occasionally. However, it seems like an unrealistic dream now,” he said.

Zhang is the only breadwinner of his family and he relies solely on his salary to support his wife and eight-year-old daughter. While he receives a 30,000 yuan a month in pay, his employer does not have an annuity programme, which means after retirement Zhang will have to rely on the state-run pension programme, and will get less than half of his present salary.

Unlike the United States and Canada, China has an underdeveloped enterprise and occupational annuity sector, with most retirees relying on the public pension system. According to a 2013 study by Peking University, only 3 per cent of over 17,000 respondents around the nation had a commercial pension and 0.2 per cent had a pension issued by a private employer.

“To make things worse, I will have to work harder to keep the job before I’m entitled to retire as the mandatory retirement age is set to be raised,” he said. “God knows how strong the competition will be when 35 is already deemed old in China’s internet sector.”

Discussions of increases in the retirement age have occurred for years, but opposition from the public is strong. Retirement-related topics trended for days on Chinese social media after the official announcement was made in March, racking up hundreds of millions of views and critical comments.

In 2000 on the mainland, the ratio of the working age population to the ageing population (65 and above) was 10:1. It fell to just 5:1 in 2020. Even according to an optimistic projection by the United Nations, the ratio will drop further to 4:1 in 2030 and even 2:1 by 2050.

As the result, the government has no choice but to postpone the retirement age over time, according to Larry Hu, chief China economist at Macquarie Group.

“The share of the ageing population in China is at Japan’s level in 1992, and [South] Korea in 2015. And it is set to rise in the years ahead,” Hu said. “A more brutal fact is that China is getting old before getting rich.”

Both Japan and South Korea began ageing rapidly when they were roughly three times as wealthy per person.

10:42

China 2020 census records slowest population growth in decades

Last year, the annual per capita disposable income of urban households in China amounted to 43,834 yuan, and 17,131 yuan for rural households. While incomes of rural residents have been growing faster than city dwellers in recent years, the state pension system for farmers has even bigger holes.

China launched a rural pension system in 2008 under which farmers who pay an annual contribution of at least 100 yuan can receive a monthly minimum of 55 yuan when they reach 60. In comparison, urban retirees receive an average monthly 2,362 yuan in pensions across the nation in 2016, official data showed.

Zeng Wenjing, 65, receives a monthly pension of 60 yuan from her hometown village in the southwestern province of Sichuan. Living with her son and granddaughter in Beijing, she said she had been thrifty all her life.

“We farmers were left out of the social welfare net and had to rely on the land and our children when we got old. Now we are covered by a rural pension system. It’s better than before, but not enough to justify any unfrugal behaviour.”

She said she had not bought any new clothes for herself in the past decade and her only entertainment was dancing in outdoor squares, which is free of charge. “I always told my son to be frugal and save every penny to prepare for the days after retirement when incomes are likely to be substantially lower,” she said.

Cai Fang, vice-president of CASS and a leading demographic economist in China, said China had reached its Lewis turning point, or the decline of the working age labour force, in 2010, putting an end to decades of double-digit growth.

“China’s population could peak before 2025,” he told an event organised by Caijing Magazine last month. “The new [turning point] could cause growth to plunge and lead to insufficient demand. It will generate an unfavourable impact on our push for consumption.”