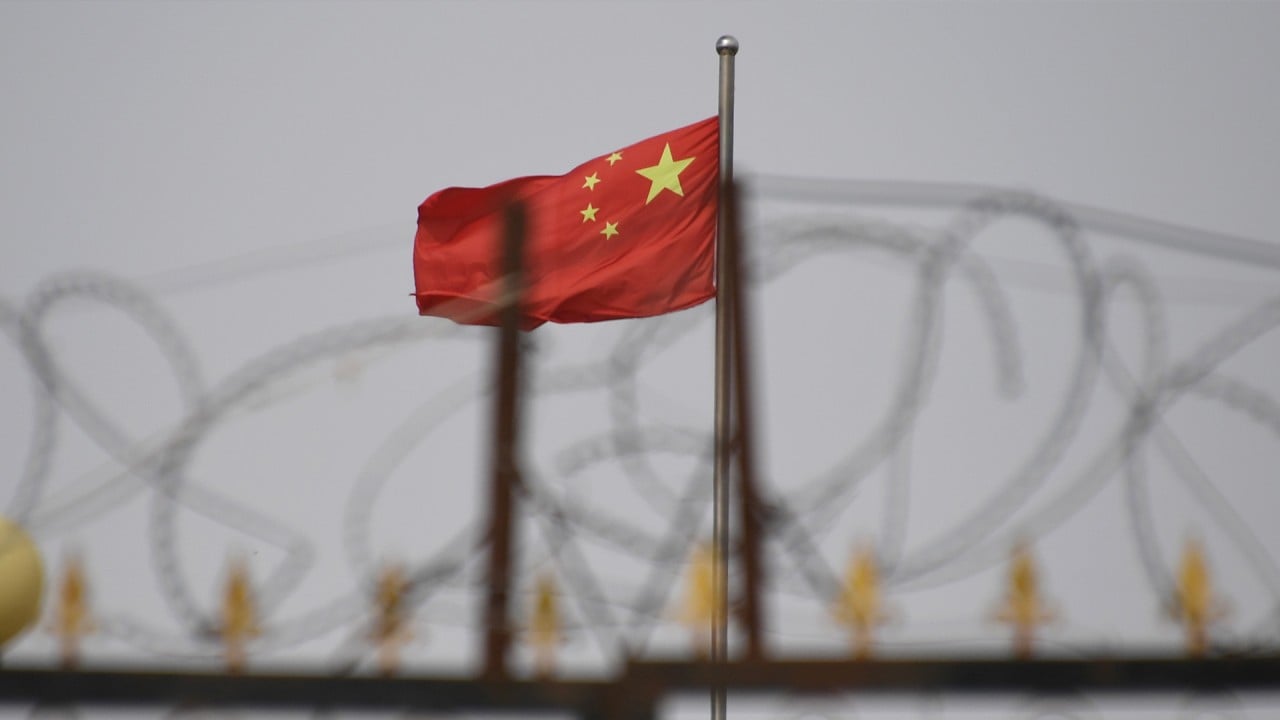

China’s Xinjiang policies ‘poorly explained and ruthlessly executed’

- Chinese experts say the country’s leaders share some of the blame for the war of words with the West over treatment of Uygur minorities

- Western accusations of genocide and forced labour based on ‘guesswork and unverified testimonies’ in the absence of first-hand information

International pressure against China over its Xinjiang policies has gained traction in recent months, with China criticised over the treatment of Uygur Muslims in Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. China has denied allegations of forced labour and detention. We look at the issues in this series.

It was 65 years ago last week – on April 25, 1956 – that Mao Zedong spelt out how China’s ethnic minorities should be governed, in a seminal speech to the Politburo outlining his vision of a socialist China and its path towards modernisation.

The speech, “On the 10 Major Relationships”, signalled a break from the Soviet model which the Chinese Communist Party had followed since it came to power in 1949. Instead, Mao said, the party must find its own way in building socialism, developing the economy and sharing power with other political parties.

The same was true of China’s policies towards its ethnic minorities. “We must sincerely and actively help the minority nationalities to develop their economy and culture. In the Soviet Union, the relationship between the Russian nationality and the minority nationalities is very abnormal. We should draw lessons from this,” Mao said in a reference to policies that promoted Russian nationalism.

“The population of the minorities in our country is small but the area they inhabit is large. The Han people comprise 94 per cent of the total population, an overwhelming majority. If they [the Han] practised Han chauvinism and discriminated against the minority people, that would be very bad. And who has more land? The minority nationalities occupy 50 to 60 per cent of the territory.”

These included bonus points for ethnic minorities on their university and public service recruitment examinations, giving them a leg up in their competition for jobs with Han Chinese.

Most notably, many ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang were allowed to have more than one child during China’s one-child policy, implemented from 1979 until 2015 to control the country’s growing population.

Beijing takes foreign media to Xinjiang in bid to dispel suspicion

“Genocide? I don’t understand how such lies happened,” said Yang Shu, former dean of Lanzhou University’s Central Asian Institute in the northwestern province of Gansu. “By definition, genocide should mean planned and mass slaughtering of people. But the population of the ethnic minority people in Xinjiang has been on the rise,” he said.

“For many years we practised strict population control on Han Chinese but among ethnic minorities, especially those in rural areas in southern Xinjiang, the phenomenon of having extra kids was very common.”

The United Nations Convention on Genocide define genocide crimes as the mass killing of members of an ethnic group, and also policies that cause serious bodily or mental harm, deliberately inflicting conditions designed to destroy the group, imposing measures to prevent births within the group or forcibly transferring children to an ethnic group. However, UN human rights courts have stated that such definition also requires a high standard of proof that the destruction of a national, ethnic, racial or religious group is intentional.

Yang and other academics who have studied China’s ethnic minority issues say the Western criticism is based on “guesswork and unverified testimonies”.

02:46

UK parliament declares Uygurs suffering ‘genocide’ in China’s Xinjiang

“They have not actually seen and experienced what’s happened in Xinjiang,” Yang said. “Western media doesn’t have first-hand information.”

However, the academics acknowledged that Chinese leaders should also share blame for the increasingly raucous attacks and counter-attacks with the West over Xinjiang, and that policies to counter terrorism and religious extremism and maintain social stability had been poorly explained and ruthlessly implemented.

Following the appointment of Chen Quanguo as party chief in 2016, the security apparatus in the region underwent a massive expansion, with the construction of a network of detention facilities, strict surveillance and an enhanced political indoctrination drive.

“The execution of some of our policies at the local level has gone overboard, like the policing [by local cadres] which may have gone too far in ensuring social stability,” said Li Sheng, former director of the Research Centre for Chinese Borderland History and Geography at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a think tank in Beijing.

“The [cadres’] original intention might have been good and [they] didn’t mean to mess up Xinjiang. However, the execution [of policies] was varied and not of a high standard,” he said. “[But we should understand that] such problems exist everywhere. Didn’t it happen in the US where police officers have taken people’s lives in the execution of the law?”

According to the academics – some of whom have previously advised the Chinese leadership on Xinjiang – it was both imperative and legitimate for Beijing to crack down on terrorism after a series of violent and bloody attacks, and also to rethink the country’s ethnic minority policies.

Why getting to the heart of Xinjiang forced labour claims is so hard

The most alarming attack happened in 2009, when anti-Han Chinese rioting broke out in the Xinjiang capital Urumqi, prompting retaliatory Han attacks on Uygurs, leaving 197 people dead and another 1,721 injured.

The attacks spilled to Beijing in 2013 and a year later to Kunming in southwestern Yunnan province. A series of bomb and knife attacks in Urumqi in the spring of 2014 – on the heels of Xi Jinping’s first visit to the region as president – prompted the leadership to announce a strict crackdown. Police said last month that China’s “battle against terrorism” had been a success, with no terrorist attacks for four consecutive years.

“The situation was very precarious then, as China’s governance of Xinjiang – not to mention stability – became questionable,” said Yin Gang, a Middle East specialist at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. But a major mistake had been a reluctance to be transparent and open about the problem, he said.

“The biggest problem was the lack of transparency, and simplicity and crudeness [in implementing the policies],” said Yin, who has been studying Xinjiang issues for nearly 20 years.

While imposing a news blackout over the incidents and subsequent crackdown had made it easier for Beijing to project an image of stability and unity, experts said the high-handed control and secrecy also bred misunderstanding and gave room for malicious attacks – especially as independent researchers were denied opportunities to understand the real picture on the ground.

03:36

Beijing hits back at Western sanctions against China’s alleged treatment of Uygur Muslims

“If China and the West had real dialogue and exchange of information, then the problem [over Xinjiang] would not have become as serious as it is today,” Yin said. “Both sides should share responsibility over this.”

It is only in recent years that Beijing has begun to make public more details of the terrorist attacks, after a deluge of criticism. “It is necessary to increase transparency and strengthen academic exchanges between China and foreign countries, which is good for dispelling rumours,” Yin said.

The accusations have prompted the United States to describe China’s actions as “genocide”, but Beijing has defended the network of camps, saying they are designed to counter extremism and offer vocational training and denied using forced labour. Some Chinese observers and Western scholars have also challenged some of the accusations and the validity of some of the accusations.

02:27

US declares China has committed genocide in its treatment of Uygurs in Xinjiang

Ma Rong, a professor with Peking University, was among the first Chinese social scientists to suggest, in 2004, that China should strengthen national identity education by “depoliticising” ethnic issues, arguing that preferential policies based on ethnicity could endanger social cohesion.

In a 2019 speech, Xi said all ethnic groups in China should be treated equally, suggesting that the policy of giving minorities preferential treatment in certain areas would end.

Yin said the shift had been a step in the right direction. “[The policy] needed adjustment. First of all, we are all citizens, independent of what ethnicity we belong to, so we should all have equal rights in terms of employment, education and joining the Communist Party. In other words, giving ethnic minority people special preferences is a form of discrimination so we should dilute the consciousness of ethnicity and stress equality more.”

British parliament declares Uygurs are suffering ‘genocide’ in Xinjiang

A social researcher, who requested anonymity because of the subject’s sensitivity, said Beijing’s philosophy on Xinjiang had shifted to focus on “equal treatment and governance by law” instead of emphasising ethnic differences — a policy derived from the Soviets

“After the founding of the People’s Republic, our ethnic minority policies were largely modelled on that of the [former] Soviet Union and mostly of Stalin’s. In retrospect, many of our policies [in Xinjiang] have gone overboard,” the researcher said.

“Sometimes our policies were too generous, offering a lot of preferential treatment, but the effects were not good. But then sometimes we were too harsh in our crackdown. So we have not had a good grasp of the policies and the execution was poor.”

01:54

China hits back at UK claims of forced sterilisations and other human rights abuses against Uygurs

Another researcher from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, who asked not to be named because he was not authorised to speak to the press, agreed that the time had come for Beijing to adopt a more consistent approach.

“China’s ethnic policies often go from one extreme to another – either giving too many benefits or exercising relentless suppression,” he said.