The mysterious rise and fall of China’s scandal-hit ‘vaccine queen’

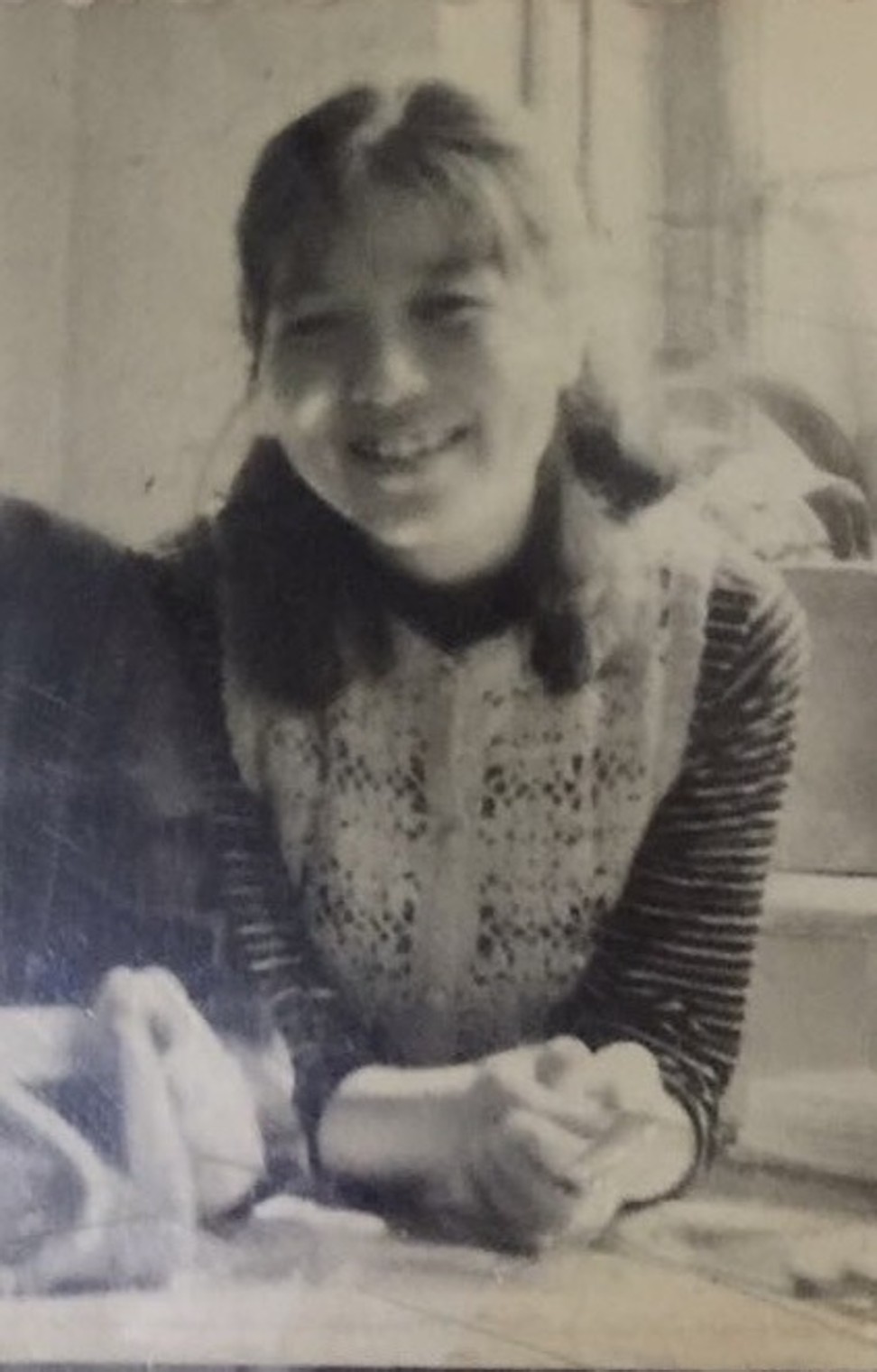

Changsheng Bio-tech chairwoman Gao Junfang is behind bars. But just how did a girl from rural China become a super-rich businesswoman, and what role did her former boss play in her stellar rise?

On a busy street in Changchun, a city in northeast China that was once the capital of Japan’s puppet state Manchukuo, two tired-looking security guards stand at the entrance to a vast but apparently deserted commercial complex. A broken sign reads “Changchun Institute of Biological Products”.

Across the street, in a residential block for retirees from the institute, several people remain in shock and disbelief at how Gao Junfang, a former colleague who rose to become China’s “Vaccine Queen”, became embroiled in one of the biggest health care scandals to hit the country in years.

Chinese President Xi Jinping orders crackdown over ‘appalling’ vaccine scandal

As chairwoman and one of the biggest shareholders of Changchun Changsheng Bio-technology – an offshoot of the institute – Gao was one of the wealthiest women in China.

But after hundreds of thousands of the company’s three-in-one DPT vaccines for diphtheria, polio and typhoid were found to be ineffective, and production and inspection records for its rabies vaccine were found to have been fabricated, she is now facing ruin.

Since July 23, 18 people, including Gao, her fellow Changsheng executives, and others associated with the company, have been arrested.

While the next chapter of Gao’s life will be decided by China’s judicial system, her rise to super-rich business owner – Forbes China in 2016 put her fortune at US$1 billion – is a matter for rumour and speculation.

Vaccine scandal: the Chinese officials who defy disgrace to rise from the ashes of public crises

For some of those who witnessed Gao’s rise from country girl to billionaire, the person at the centre of the mystery is a man called Zhang Jiaming, the former boss of the research institute.

“If there’s anyone who knows exactly what happened regarding Gao’s rise over the years, it must be Zhang Jiaming,” said an octogenarian woman who asked not to be named but told the South China Morning Post she worked at the institute for several decades before retiring in the 1990s.

Despite some newspaper reports claiming Gao was the daughter of Jilin’s top Communist Party official, she was actually born into an ordinary family in a rural area of the province in 1954.

After graduating from a local technical college she joined the state-owned institute as an accountant in the 1970s, former colleagues said.

With her impressive knowledge of finance, easy-going personality and good social skills, she soon became a hit with her superiors, they said.

Most notably, she was spotted by Zhang .

Li Changtai, now in his 80s, worked for many years as Zhang’s deputy at the institute. He told Chinese financial news site of NetEase recently that it was no secret among the people who worked there that Zhang and Gao were perceived as being close .

Li said he first realised what was going on when he was effectively forced into giving Gao her first major promotion.

Chinese vaccine maker found to have forged production data for over four years

Changchun Industry – the forerunner to Changsheng Bio-tech – was set up in 1992 as a commercial unit of the institute.

Zhang appointed Li, who at the time was head of the institute’s finance department, to be the company’s new general manager, and promoted Gao to replace him. He also made her deputy general manager of the new firm.

“Gao wasn’t my choice to succeed me as head of the finance department,” Li said, adding that she was just a regular accountant at the time.

Less than two years later, in 1994, Gao replaced Li as the boss of Changchun Industry and it was then that she appeared to begin building her fortune.

When the new company was set up, the institute had turned to its employees to raise part of the initial capital in return for shares.

Tian Rongtong, an 87-year-old former engineer who had also run the vaccine extraction team at the institute, said that middle managers like him were entitled to 6,000 shares while regular workers got 4,000.

Many of those employees soon parted company with their stakes, however, when Gao, soon after taking over as general manager, initiated a repurchase scheme.

India bans imports from firm at centre of Chinese vaccine scandal

A former head of production at Changsheng Bio-tech, who asked not to be named, said that between 1995 and 1996 hundreds of workers – from the lowest ranks to middle managers – were either enticed or forced into selling back their stock.

“They were offered 1 yuan per share, which was quite appealing for some of the ordinary workers as it meant they immediately pocketed about 4,000 yuan [US$585]. Most of them only made about 700 yuan a month at the time,” he said.

“But others were reluctant to sell as they expected a three- or fourfold increase in the share price once the company was publicly listed.

“None of us are idiots. We didn’t want to sell our shares. But there was no option, we were forced to sell every single share in our hands,” he said.

Now 81, the former production chief said he was friends with Zhang in the 1990s and when he heard the rumours about his ties with Gao he decided to pass on what he knew.

It was not a good idea.

“Zhang didn’t say anything at the time,” he said. “But a year later I was transferred and made to work in another department.”

As new vaccine scandal grips China, parents say they’ve lost faith in the system

Towards the early 2000s, China embarked on a massive reform programme for its state-owned enterprises, which led to many inefficient, planned-economy-era firms being privatised, listed on the stock market, merged or folded.

While some regarded the move as a leap forward for Beijing’s ambitions to become a market economy, others criticised what they saw as the transfer of valuable state assets into private hands by corrupt officials.

At Changsheng Bio-Tech, the privatisation process happened in 2003, a year after its name change.

During the share sale, Gao managed to secure a 35 per cent stake for about 40 million yuan, The Beijing News reported. Before the vaccine scandal broke last month, the Shenzhen-listed company had a market value of about 24 billion yuan.

There were also challenges to the authority’s decision to approve the sale. Although Beijing’s newly established State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission had issued strict rules to forbid the management from buying out the state-owned enterprises they worked for, the Changchun government still gave the green light to Changsheng’s management buyout.

The price of the shares Gao bought was also lower than the third-party bidder’s offer, Beijing-based newspaper The Economic Observer reported. Nonetheless, the authority still decided to sell the state-owned shares to Gao.

Where Gao got her initial capital from remains a moot point. The former head of production said he had no idea how she could have raised such a sum.

“In 1993, I made no more than 15,000 yuan a year,” he said.

In an interview with The Beijing News in late July, Zhang Minghao – Gao’s son with Zhang Youkui – sidestepped a question about his mother’s source of funds, saying only that the share purchase had been approved by the relevant authorities and that it was unfair to scrutinise it using today’s standards.

He also denied that Gao’s success within the company and subsequent fortune had anything to do with nepotism.

“Go ask my mother how many leaders she knows,” he was quoted as saying, adding that Gao had adopted a modest way of life.

Rabies vaccine scandal reveals China’s tattered moral fabric

Zhang Jiaming remained as boss of Changchun Institute of Biological Products until his retirement in 2000. Eight years later he was named as a board director of Changsheng Bio-Tech, a position he held until 2014. Gao was also made a board director in 2008, while her former institute boss Li resigned from the board in 2006. In 2011, Gao was joined on the board by her son, Zhang Minghao, while her husband, Zhang Youkui, remained a major shareholder.

By the time of the DPT scandal, Changsheng Bio-Tech was the country’s second-largest vaccine producer. And that is the memory Zhang Jiaming, who died in 2017, will have taken to his grave.

What else he knew about the company’s rise and the role Gao played in it is a matter for speculation. Though the retired octogenarian is in no doubt he held the key.

“As the top leader of the institute, Zhang knew every detail of the things that were done during the privatisation process,” she said.

“Every question would be answered if Zhang was still alive.”