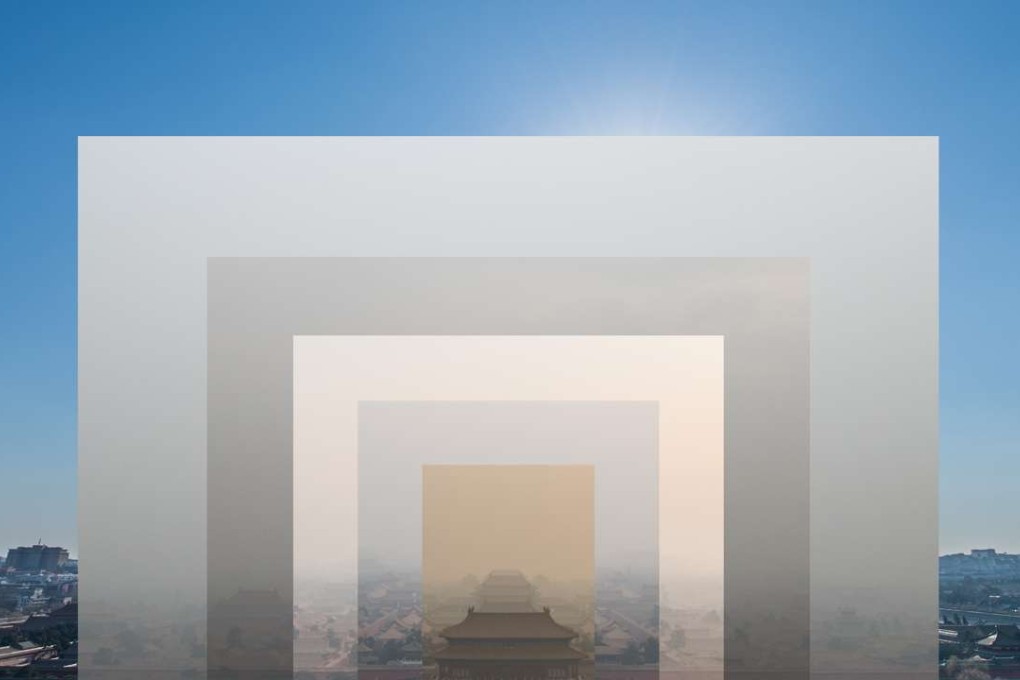

China firing blanks in ‘war on pollution’ as smog worsens

Getting regions to follow Beijing’s lead proves difficult, with stimulus-induced uptick in industrial activity adding to problem

Vowing to fight pollution with the same determination that China had fought poverty, Li’s pledge – the highest-level acknowledgement to date of the seriousness of the issue – offered a glimmer of hope that such blue skies might one day become the norm.

But fast fast-forward three years and that hope is dwindling, with a thick layer of choking smog blanketing large swathes of northern China, including the capital, this winter – one of the most polluted in years.

In his work report to the NPC in March 2014, Li described smog as “nature’s red-light warning against inefficient and blind development” and unveiled detailed measures to tackle the problem.

But despite the investment of much effort and money, analysts said lax enforcement of state policies, laws and regulations combined with concerns about the slowing economy have watered down Beijing’s ambitions to clear up the air.