What Philippine use of legal weapons could mean for South China Sea dispute with Beijing

- Manila looks likely to pass a law outlining its claims to the disputed waters in the hope of strengthening its hand following a series of clashes

- Chinese observers say the move risks further escalating tensions, but could also herald a fresh attempt to take the matter to the international courts

Last month senators unanimously approved the Philippine Maritime Zones Bill, which defines the parts of the sea that fall under the country’s jurisdiction and the legal powers that Manila can exercise there, prompting a swift backlash from China.

Days later, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, without naming any specific countries, said Beijing rejects any “distortion” of maritime law and will fight back against “deliberate infringements” in the waterway.

There have already been a series of clashes between the two countries’ coastguards, including collisions between ships and the Chinese use of water cannon, centred on attempts to bring supplies to troops stationed on the Philippine-held Second Thomas Shoal.

Beijing protests over ‘recent negative China-related remarks’ by Philippines

These incidents mean that the vital waterway – which carries one-third of global shipping and contains vast mineral, oil and gas resources – is widely seen as a potentially explosive global hotspot.

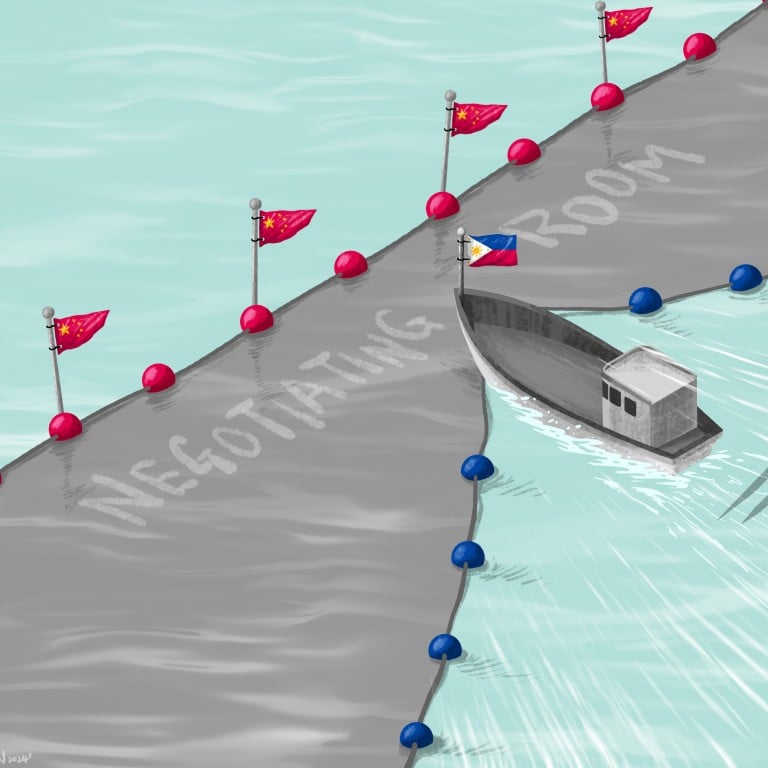

But Chinese analysts say that if the act is signed into law, it is likely to further narrow the negotiating room between the two neighbours while jeopardising ongoing talks between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) on a code of conduct for the waterway, where there are multiple overlapping claims.

As it would reinforce Manila’s claims over contested islands, reefs and their adjacent waters, the Philippine law could also raise the bar for any future efforts to resolve the dispute between the two countries, according to Liu Xiaobo, director of the Centre for Marine Studies at the Beijing-based think tank Grandview Institution.

“Negotiation should at least be in a space where both sides can be flexible and can compromise, but after you have cemented all the rights through [domestic] legislation, you can hardly compromise,” said Liu, who added that he had seen no sign that the two sides were pushing for territorial talks at present.

He also said China’s own position was unlikely to change and warned the new law was “pouring oil on the flames”.

“The dispute is only a small part of the bilateral relationship, the recent moves may be amplifying the dispute. Whenever you talk about China-Philippines relations, everyone’s first reaction is all about the frictions in the South China Sea,” he said.

Is Philippines at front line of ‘WWII-style war’ with China over disputed sea?

The recent senate vote on the legislation, which includes an amendment that would allow the Philippines to claim any artificial islands that fall within its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), appears to mark a shift in the Philippine public debate over the need to resort to legal means.

Several previous attempts to enshrine Manila’s claims into law have failed to get through the upper house, but several versions of the bill have been passed by the House of Representatives – most recently in May last year.

The legislation will “provide the country with a strong diplomatic negotiating tool in pursuing our interests”, Philippine Senator Francis Tolentino, the main sponsor of the Senate version of the bill, said in November.

But according to Zhu Feng, executive director of the Collaborative Innovation Centre of South China Sea Studies at Nanjing University, the bill reflects rising nationalist sentiment in the Philippines.

Zhu added that Washington’s “high-profile” intervention in the South China Sea under its Indo-Pacific strategy had given politicians in the Philippines, a key US ally, the confidence to confront Beijing.

He said the bill, as a “unilateral” act, would be detrimental to regional stability and the ongoing negotiations about code of conduct for the South China Sea.

“[The move] is a huge step backward from the existing achievements that China and Asean have made over the years in maintaining stability in the South China Sea,” he said.

Could 3-way meet with the US draw Japan to help Philippines in South China Sea?

China and the 10-member bloc have set a goal of finally agreeing a code of conduct after years of negotiations by late 2026 and started the third reading of a draft text last October.

Efforts to provide a legal underpinning to the Philippine claims to the South China Sea date back to at least 2009 and the presidency of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, when a law set out the country’s archipelagic baselines, providing a reference point for marking out the country’s territorial seas and exclusive economic zone under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

The law identified both the Scarborough Shoal and Kalayaan group of islands, part of the Spratly chain, as belonging to the Philippines, triggering protests from rival claimants China and Vietnam.

It was also seen as a move to lay the groundwork for the 2016 arbitration in The Hague.

China claims most of the South China Sea – an area marked out by the so-called nine-dash line or U-shaped line – but the Permanent Court of Arbitration, a UN body, ruled that there was no legal basis for Beijing’s claim to “historical rights” within the area.

The tribunal also ruled that the Spratly Islands and the Scarborough Shoal are not islands in the legal sense, which opened avenues for surrounding nations to assert rights over those features through an exclusive economic zone.

This is defined as a zone extending up to 200 nautical miles (370km) beyond a state’s coastline where it does not have sovereignty but has the right to exploit the natural resources within that area.

Beijing has consistently said it will not accept The Hague ruling.

Meanwhile, Philippine legislators have been incorporating the tribunal’s findings into the various drafts of the maritime zones bill put before Congress since 2021, including the recently passed versions.

Manila says Beijing’s South China Sea proposals go against national interests

Liu, from the Grandview Institution, said the law might aim to solidify the parts of the arbitration ruling that were favourable to Manila and assert its EEZ claims so that the Scarborough Shoal and Kalayaans would fall within its maritime zones.

A clause stating that “all artificial islands constructed within the Philippine EEZ shall belong to the Philippine government” could provide a basis for developing features in the parts of the Spratly chain controlled by Manila or help challenge construction by other countries, Liu argued.

In recent years China has been developing both civilian and military infrastructure in the parts of the South China Sea it controls, including runways and accommodation for troops, while Vietnam has also stepped up its land reclamation in the Spratlys.

Beijing has lodged a formal complaint against the bill, which the foreign ministry described earlier this month as an “egregious act” that “will inevitably make the situation in the South China Sea more complex”.

Tolentino said a day later that Chinese officials’ reactions showed that “they are worried as to the future ramifications and consequences” of the maritime zones act.

Zhu, from Nanjing University, said it was possible the law could herald further international legal action from the Philippines, but warned that unilateral legislative actions at home could backfire.

“The Philippines would be hijacking international legal processes … if it were to push for domestic legislation first and then step up litigation abroad,” Zhu said.

US part of Philippines’s ‘calculated’ plan to tap oil, gas in South China Sea

“It’s important to return to diplomatic dialogue and engagement to manage disputes and move the South China Sea towards stability and cooperation,” Zhu said. “That’s in the common best interests of China and the Philippines.”

Ding, from the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, said any further international arbitration could have a greater impact than the domestic Philippine law, but China had experience of dealing with that situation.

“If you do that again, it won’t solve the problem but set back China-Philippines relations, let the South China Sea issue become more complex and difficult and delay the negotiations on the code of conduct,” he said.

He also warned that it would put Asean in an awkward position and risk splitting the bloc.

Liu also said Beijing could respond to the Philippine legislation by marking out its territorial baselines in seas around the Spratly Islands, which it calls the Nanshas, or clarifying the U-shaped line’s legal status.

“But we may have to consider the negative impact”, he added. “Taking such domestic legislative action will surely further escalate disputes in the South China Sea.”

China’s own domestic law claims the Scarborough Shoal and the Spratly Islands as part of its territory and asserts its sovereignty and rights over various nearby maritime zones.

But it has yet to formally declare the geographical boundaries of the maritime zones for those two contested areas.

Liu said he was not optimistic about tensions between the two countries easing.

He expected Macros would continue to take a tough stance against Beijing, while China had a “limited” range of ways to respond.

China poised for ‘long game’ with Manila over South China Sea disputes

“Maintaining the status quo is certainly best for us,” he said, adding that the use of force would only draw Washington more deeply into the region through its mutual defence treaty with the Philippines.

But he said China did still have some advantages, including a bigger coastguard than the Philippines.

He also said that the BRP Sierra Madre, the old warship that Manila grounded on the Second Thomas Shoal in 1999, was at increasing risk of collapse.

He said the Philippine side’s recent efforts to repair the ship, which serves as a makeshift base for its troops, showed they sensed the urgency of the matter, adding: “When it comes to keeping the status quo, time is on China’s side.”