Why China is now looking to have its say on international law

- Beijing used to steer clear of multilateral tribunals, preferring to go one on one in disputes

- But four years after a decision against it on the South China Sea, Beijing is taking more of an interest in global rules and the way they are made

Over the years, Beijing has preferred to use bilateral talks to resolve issues and safeguard its interests.

But there are signs that this could be changing amid the backlash from The Hague case and as China extends its international reach.

Now, China is seeking to shape the rules of broader international law to confront a spectrum of legal challenges, from its handling of the coronavirus pandemic to maritime disputes in the South China Sea.

South China Sea: the dispute that could start a military conflict

The most recent sign of the change in strategic tack came in October, when Yang Jiechi, the country’s diplomat and a member of the Communist Party’s Politburo inner circle, stressed the importance of international law in addressing the challenges facing China – from territorial disputes to human rights.

“Emerging market countries and developing countries, including China, are increasingly advocating adherence to the basic principles of international law and looking for establishing a more just and reasonable international order and a global governance system with equal participation,” Yang wrote in Qiushi, the party’s journal of political theory.

He said China had to play a more active role in setting norms to strengthen the application of international law in areas such as oceans, polar regions and artificial intelligence.

01:33

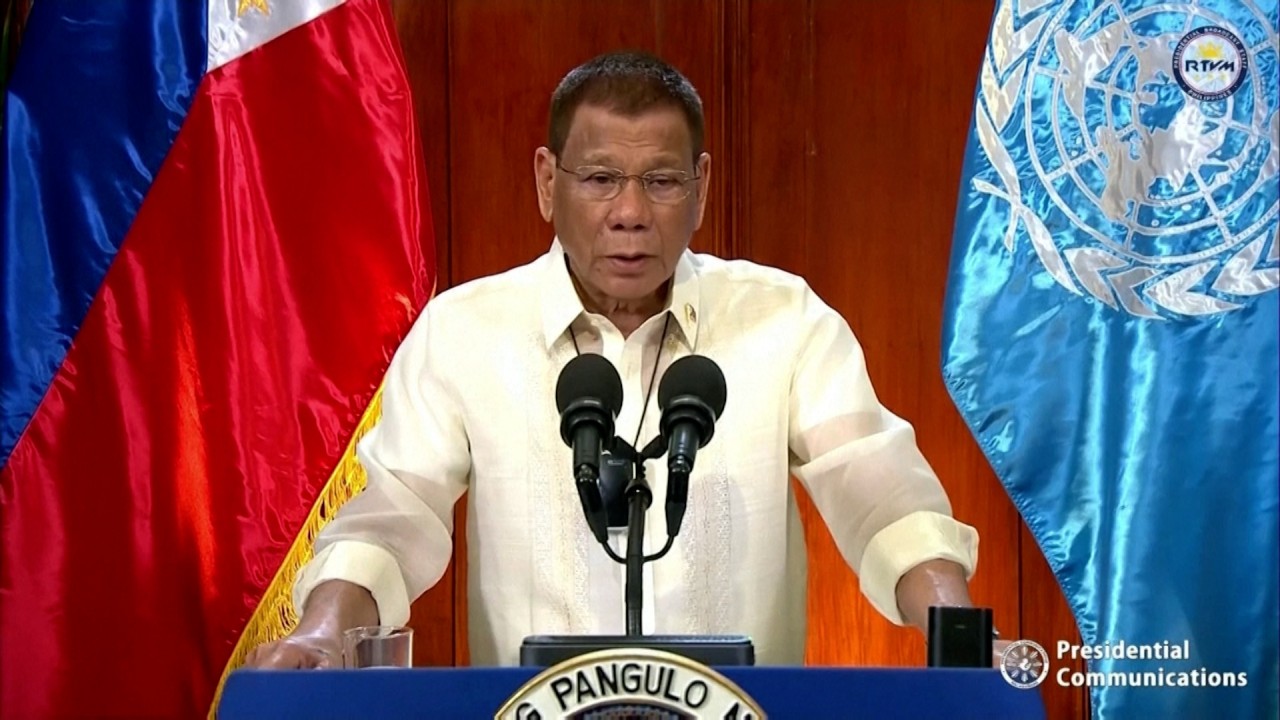

Philippine President Duterte raises 2016 South China Sea tribunal win at United Nations

Beijing’s unwillingness to take part in the proceedings contributed to a strong backlash from other claimants and the United States, who accused China of defying international norms.

Peking University international relations professor Liang Yunxiang said there was an understanding in China that it needed a new tactic.

“From the [perspective] of foreign policy, since the South China Sea arbitration case, as well as in the context of the ongoing friction between the US and China and the West’s constant emphasis on a rules-based international order, there is an urgent need to use international law to defend national interests,” Liang said.

China can also expect to face challenges in other jurisdictions and legal systems, including a number of class actions in Europe and the United States against its handling of the pandemic.

Zheng Zhihua, an international law expert with Shanghai Jiao Tong University, said he expected these kinds of cases to increase.

“I think China needs to have some plans in hand,” Zheng said. “So that we can formulate a strategy to be chosen in the end.”

China needs more experts in international law to beat US coronavirus lawsuits, academic says

More Chinese legal experts and diplomats should play an active role in setting new international order, according to Jia Guide, director general of the Chinese foreign ministry’s treaty and law department.

During an international law seminar in Beijing last month, Jia highlighted climate change, biodiversity protection and talks on legally binding human rights rules for transnational corporations as areas of particular importance, with the last of these crucial to China’s overseas investment.

He added that while it is legitimate to stop multinational companies from violating human rights, it would affect business sentiment if the conditions were too onerous.

“We have to make a balance between seeking development and protecting human rights,” Jia said. “The problem with the text of the current legal instrument is that it is overly inclined towards protecting victims and excessively aggravating the legal responsibility of multinational companies to respect human rights.”

02:17

Malaysia’s Foreign Minister says South China Sea still a major unresolved issue

But changing the rules to better suit China is easier said than done, given that Beijing’ engagement in international law is often seen largely as a rhetorical strategy rather than a meaningful part of its policymaking.

“Law is lower than political and military power,” Liang said. “It is simply seen as a tool to realise power and interests.”

Zheng said China could appoint its representatives into international institutions, but its lack of experience in the area might make it hesitate to apply international law.

“Lawmaking is a very delicate process that requires professional opinions at every step, and without such talent, it would be difficult to say that your views have been reflected in the text of a draft treaty,” he said.