South China Sea: does one-on-one mean a one-sided deal for Malaysia?

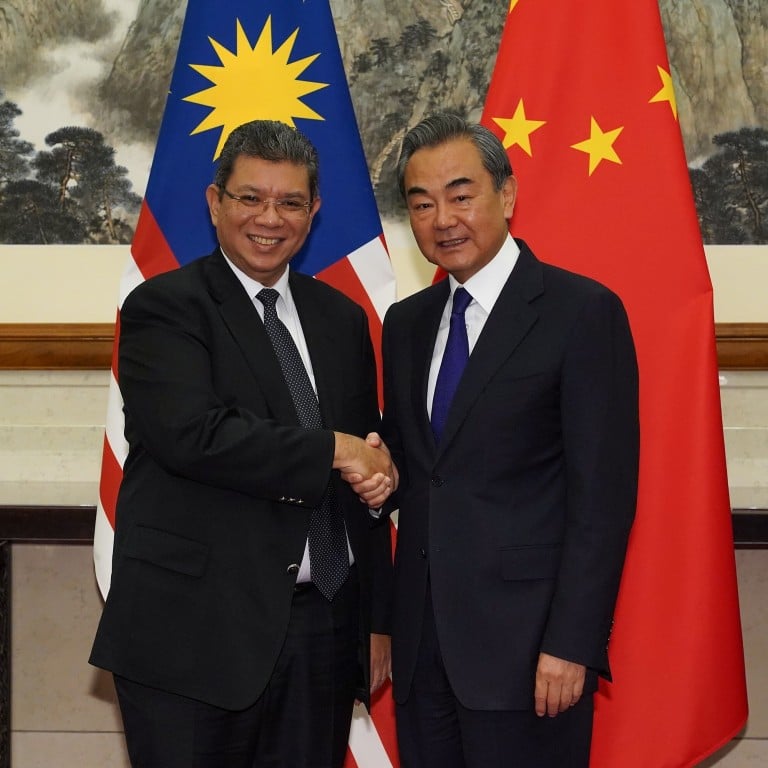

- The foreign ministers of the two countries agreed last year that they would pursue one-on-one talks to settle their differences over the contested waters

- But insiders in Kuala Lumpur say the bilateral route sets a dangerous precedent

While Kuala Lumpur was not the most vocal opponent of Beijing’s claims in the area, it had long been reluctant to engage in such negotiations.

Instead it has sought to chart a course between not antagonising China and quietly pursuing its own plan for oil and gas exploration in the contested waters.

With tensions rising with the United States over the South China Sea, Beijing has been pushing Kuala Lumpur for a breakthrough but with a year already gone since the agreement there has been no sign of progress – or of any more to come.

South China Sea: the dispute that could start a military conflict

China’s aim is to have some kind of bilateral dialogue mechanism with each claimant, focusing more on joint development of natural resources and less on arguing over territorial disputes.

It is a tactic Beijing has pursued with Manila and Hanoi but to the insiders of Malaysia’s foreign policy establishment, China’s approach puts smaller claimants at a disadvantage.

“Our official position is that we are open to this, but we have been trying to push it back as much as we can. The pandemic has given us a good excuse to stall it,” a person familiar with Malaysia’s policymaking said.

“We don’t think this is going to be a good deal for us, especially when we look at how little the Philippines and Vietnam have been able to get out of this.”

02:17

Malaysia’s Foreign Minister says South China Sea still a major unresolved issue

Another Malaysian policy insider agreed, saying that setting up a bilateral consultation mechanism “is seen as a dangerous precedent”.

“We want the discussions with China to be multilateral, not bilateral. The bilateral route is what China wants … Ultimately, they want to take us on one by one.”

In response, China’s foreign ministry said the bilateral dialogue mechanism was aimed at improving trust between the two countries.

“This mechanism is aimed at enhancing understanding and mutual trust between the two sides, properly managing disputes, advancing maritime cooperation, and jointly safeguarding peace and stability in the South China Sea,” it said.

China and Malaysia had maintained communication on the matter, but did not provide the scope or any further details about the mechanism, it said.

China’s defence minister heads to Brunei, Philippines after visits to Malaysia and Indonesia

China has had similar talks with Vietnam since 2014 to discuss maritime delimitation in the sea area outside the mouth of the Gulf of Tonkin, or Beibu Gulf in Chinese, and joint development of resources. The latest meeting was held on September 9 and yielded an agreement to continue working for progress on the two issues, according to China’s foreign ministry.

Richard Heydarian, a Manila-based specialist on Southeast Asian politics, said the bilateral approach had merits and limitations.

“This is a mixed baggage. On one hand, it absolutely makes sense for China and claimants in the South China Sea to maintain institutionalised and sustained communications,” he said.

“In the case of the Philippines, the [bilateral consultation mechanism] was very helpful because we were operating from a very low base, which was the state of awful bilateral relations during the [former president Benigno] Aquino administration.

“So the Duterte administration has correctly emphasised that for sustained communication and [to prevent] unwanted clashes.”

But Heydarian said Southeast Asian claimants remained suspicious of China’s intentions and the efficacy of such a mechanism.

While the dialogue had opened a channel for smaller claimants to state their position and concerns, China’s foreign ministry, which is in charge of the dialogue, lacked the power to make decisions and solve problems, he said.

“On the part of Asean, I think we should welcome the BCM, including Malaysia, which has a far better relationship with China throughout the decades than the Philippines,” Heydarian said.

“But at the same time [we must] acknowledge that there are limitations to it and we should ensure that it does not chip away at our efforts to address this international dispute through multilateral mechanisms.”

Holding bilateral talks with China should not stop Asean countries from seeking help from other powers, he said.