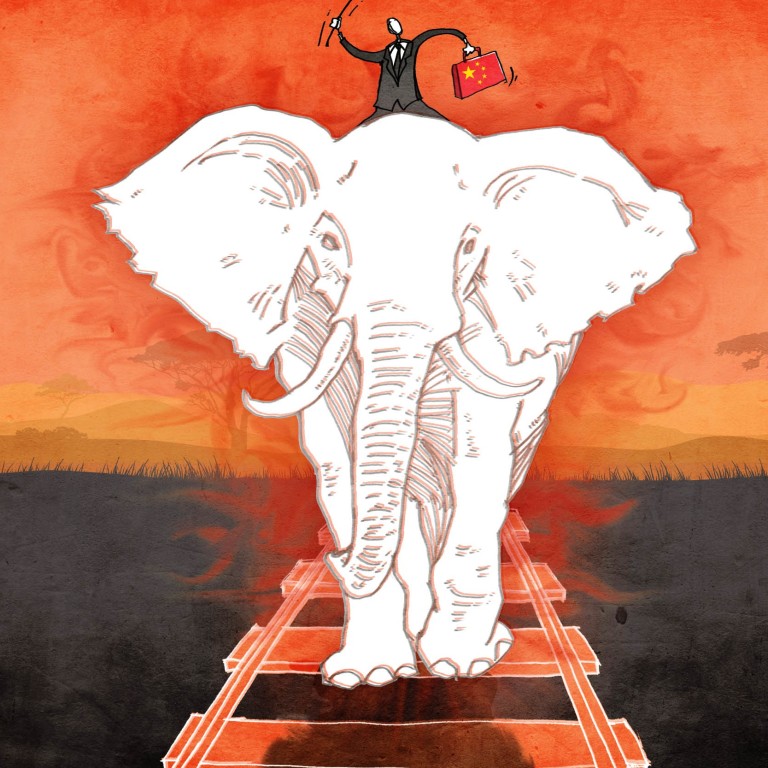

Kenya’s Chinese-built railway is a hit with travellers, but is this safari line a massive white elephant?

- Despite the popularity of the new Nairobi-Mombasa line with travellers, critics fear it has come at a heavy price for the country as a whole

- Railway was primarily designed to carry freight, but official statistics suggest revenues generated are not enough to cover fees paid to Chinese companies

One new railway station just outside the Kenyan capital Nairobi has the sleekness of an architectural masterpiece.

It could easily be mistaken for a terminal at a top new international airport, and trains leaving from the station are so popular that tickets frequently sell out.

With a price tag of US$3.2 billion for the construction of the new railway it serves, the terminal stands out in a nation that has not seen infrastructure developments on this scale in decades.

But one other thing about Kenya’s new railway makes it exceptional: it was not only financed and built by China, it is operated by that country as well.

Since mid-2017, the Standard Gauge Railway, or SGR, has been running twice daily service each way between the Kenyan capital and the coastal port city of Mombasa.

The afternoon train pulls away from the station at 2.35pm and covers the 472km (293 mile) journey in about 4½ hours in remarkable comfort.

Before this, the rattling journey from Nairobi to Mombasa by bus could take up to 12 hours. Or there was the old British-built railway, the infamous Lunatic Express, that could take 24 hours.

China meets resistance over Kenya coal plant, in test of its African ambitions

At US$10 for economy seats, or US$30 for business class, many travellers say the new train is a bargain. From the window, there is a clear view of the plains, and elephants, lions, buffaloes and rhinos can often be seen as it shuttles through Tsavo National Park.

When the SGR train rolls into the Miritini terminus in Mombasa at 7.18pm, China’s presence is felt every bit as much as at the Nairobi station.

There, a statue of the Ming dynasty Chinese admiral Zheng He sits on a plinth greeting passengers, more than 600 years after his voyage at the head of an immense Chinese fleet to the town of Malindi further up the coast in 1418.

A plaque mounted on the statue explains: “Zheng’s fleet paid four visits to Mombasa, enhancing mutual understanding between China and Kenya, and strengthening Kenya-China friendly exchanges.”

Never mind that there was no country called Kenya back then, and China would have been known by the name of its ruling dynasty, the Ming.

Many centuries later, China is trying to connect this episode with projects such as the SGR to cement relations with this part of Africa.

At first glance, the passenger train service might seem like an unqualified success, having already moved about 3 million travellers since its launch in mid-2017. But this is not the main reason the new railway line was built.

In 2014, when Kenya took a largely commercial US$3.2 billion loan from the Export-Import Bank of China, the goal was to transport freight between the port of Mombasa and Nairobi more efficiently by train, and thus alleviate congestion on the country’s overtaxed and poorly maintained roads.

When measured against its original purpose, the freight service, in fact, has been a big disappointment. Since it launched early last year, the service has consistently failed to deliver enough goods to enable the Mombasa port to pay for itself.

The government has had to strong-arm importers to use the train and given deeper discounts to woo more, and even then it has still failed to generate sufficient traffic.

Because of this, more critics say it looks like the biggest elephant along the way is the one carrying goods from the Mombasa port.

China must be transparent to boost belt and road

On the face of it, there is nothing unusual about the idea that a new railway might have the potential to mark a new dawn for Kenya; that it could be a powerful symbol of renewed development for the East African nation.

But trouble is brewing for the country’s largest and most expensive infrastructure project since independence in 1963.

It has recently emerged that Kenya signed what critics claim is a lopsided contract with Export-Import Bank of China for that US$3.2 billion loan.

The loan contract, so far shrouded in secrecy, contains what some analysts have described as toxic clauses: terms that could see Kenya lose its strategic assets if it defaults on its loan obligations.

It was reported in December that Kenya’s auditor general, Edward Ouko, sounded a warning in a letter sent to Kenya Ports Authority management.

The letter raised concerns over the terms of the loan contract, which it said could lead to Kenya surrendering control of the Mombasa port if it defaulted on its loans.

Soon after, Hua Chunying, a spokeswoman for China’s foreign ministry, denied the reports, saying that Chinese companies and financial institutions would always conduct thorough studies to guard against “debt risks and fiscal burdens” for African countries.

But critics questioned the financial wisdom behind the project, arguing that carrying freight by rail was far more costly than by road.

Belt and road accused of wasteful spending

A report commissioned by the Kenyan government confirmed that unless the state subsidised some of the costs, the Mombasa-Nairobi rail freight service would cost twice as much as carrying the same goods by road.

Recently, Kenya’s statistics bureau heightened concerns about the revenues generated by the railway when it dramatically revised its data.

In April, it said the SGR earned about US$100 million in 2018, its first year of operations, of which about US$86.3 million came from freight.

But in a report the next month, the rail project was reported to have made just US$57 million last year, with US$40.9 million coming from the cargo business.

The statistics office said the numbers were provided by the Kenya Railways Corporation, the state agency in charge of rail assets.

As the government pays the Chinese firm slightly more than US$120 million a year in management fees, the revenue generated last year was not enough to cover its operational costs.

David Ndii, a Kenyan economist and a frequent critic of the government, said that it was not a must for publicly funded infrastructure to be commercially viable or profitable but that projects should be economically viable – meaning they must have a positive impact on society and the environment.

“There is nothing to demonstrate that the economic benefit of this project exceeds the cost,” he said.

“If we were to build a railway [we] would have made a business case by doing a new one in Lamu [340km to the north of Mombasa] because we had already planned to build a port. That port needs the cargo to be evacuated.”

The project’s operator, China Road and Bridge Corporation, declined to comment and directed questions raised to its employer, Kenya Railways Corporation.

Philip Mainga, managing director of the African firm, said that, as with any new venture, there was a fear of the unknown.

“However, we engaged the shipping fraternity, cargo owners, cargo agencies together with the importers and manufacturers,” he said.

“The benefits of efficiency were tabled considering that it takes only eight hours to deliver cargo from Mombasa to Nairobi [using the railway].”

This is the second in a series of reports in which the South China Morning Post examines the local impact of Chinese investment and infrastructure projects in Africa.