China’s human rights record, aggressive military expansion damage its soft power rating

Beijing can drive global agenda, but its soft power efforts must be congruent with its political and economic pursuits, researcher says

China’s soft power has been weakened by its hard line on foreign policy and human rights, according to an annual survey released on Thursday.

In the “Soft Power 30” report by communications consultancy Portland and the University of South California Centre on Public Diplomacy, China ranked 27th of the 30 countries to make the list, down two places from last year.

The weaker showing was mostly a result of it finishing bottom on the “Government” subindex, which measures nations’ political values, such as their position on human rights, democracy and equality, said Jonathan McClory, the report’s author and Portland’s general manager for Asia.

“China’s record in human rights and civil liberties reflects poorly among Western audiences,” the survey said, adding that “relatively low scores in competitiveness, ease of doing business, and rule of law diminish its attractiveness as a global business hub of choice”.

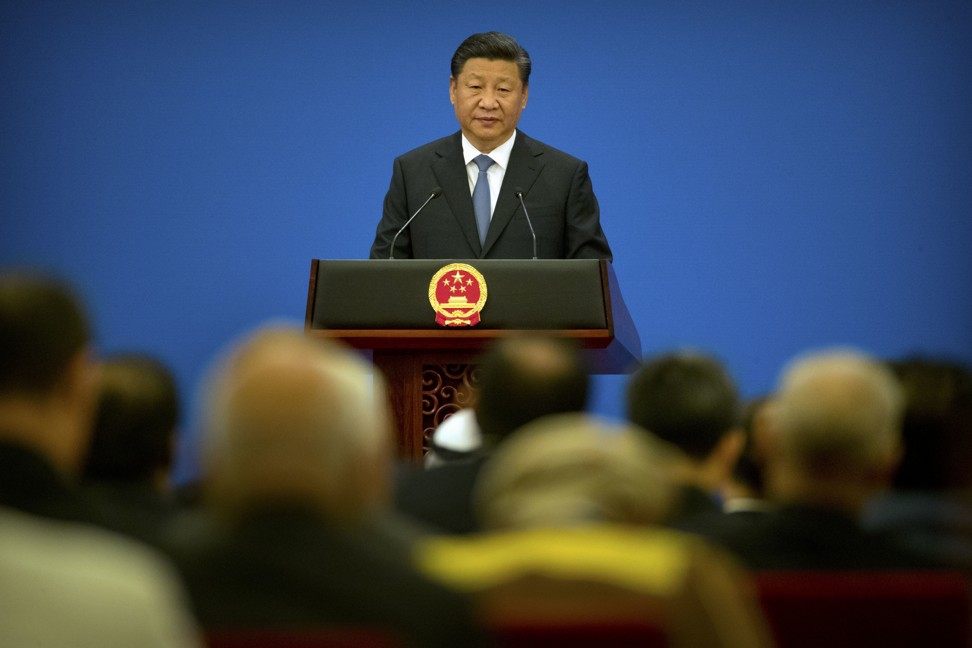

Also, while China was boosted in 2017 by President Xi Jinping’s speech at the Davos forum, in which he sought to position the country as a responsible global leader that supported globalisation and free trade, as well as the fight against climate change, that positive narrative “somewhat faded” this year, the report said.

“International attention concentrated on Xi’s decision to eliminate the two-term limit on the presidency,” it said.

Beijing’s “aggressive military expansion” had also undermined its efforts to build trust abroad, by promoting bilateral relations and through its “Belt and Road Initiative”, the survey said.

On a more positive note, China’s cultural influence – through the arts, sports and tourism – remained strong in 2018, while it also made ground in the fields of education, innovation and technology, and international engagement, McClory said.

“China has great potential to drive the global agenda forward, but increasing demands for authenticity means that its soft power efforts must be congruent with its political and economic pursuits,” he said.

“China has clearly made gains in developing its soft power between 2015 and 2018, but progress is rarely a straight line.”

Meanwhile, with Beijing and Washington embroiled in a major trade dispute, the United States also found itself sliding down the chart, to fourth place in 2018, from third in 2017 and first in 2016.

It also fell four places to 16th on the government subcategory, though still topped three of the six other composite indexes.

Joseph Nye, a Harvard professor and the originator of the term “soft power”, said the US was counting the cost of it’s leader’s hard-line approach.

“The results of this year’s study show a further erosion of American soft power,” he said. “Clearly, the Trump administration’s ‘America first’ approach to foreign policy comes at a cost to US global influence.”

The annual soft power report was launched in 2015 and ranks the top 30 nations on the scores awarded to them in seven categories by 11,000 people from 25 countries.