Trade ties drive China’s delicate dance around North Korean nuclear threat

Adam Cathcart says China’s long-term strategy remains tied to the nurturing of an entrepreneurial class in North Korea and free trade zones along the frontier

Since the Korean war, China’s relationship with North Korea has been populated with a rich array of metaphors.

The two nation’s ties are described variously as being close as lips and teeth, connected by rivers and mountains and forged in the blood bonds of brotherhood – an alliance which is intended to deter attacks from wolfish imperialists.

Since China voted to support the implementation of the latest United Nations sanctions against North Korea, these metaphors appear to have gone seriously askew. As North Korea brandishes ever more passionately its own patented threats and metaphors of nuclear weapons as the country’s “treasured sword”, the relationship with China is again under great strain.

One incident along the 1400-km shared border appears to have captured the current ethos, offering a new metaphor for the relationship – trucks full of frozen squid from North Korea stopped at a Chinese customs point near Hunchun and turned back. Squid was one of the more lucrative non-mineral commodities which the North Koreans could export legally into China, but under the new resolution, it can no longer be sold there.

Like that squid, China’s relationship with North Korea is in a highly uncomfortable state of transition, but can still be salvaged and even become lucrative. It is too early to declare a full rupture of relations, but it is also too late to say that the relationship can emerge undamaged from recent events.

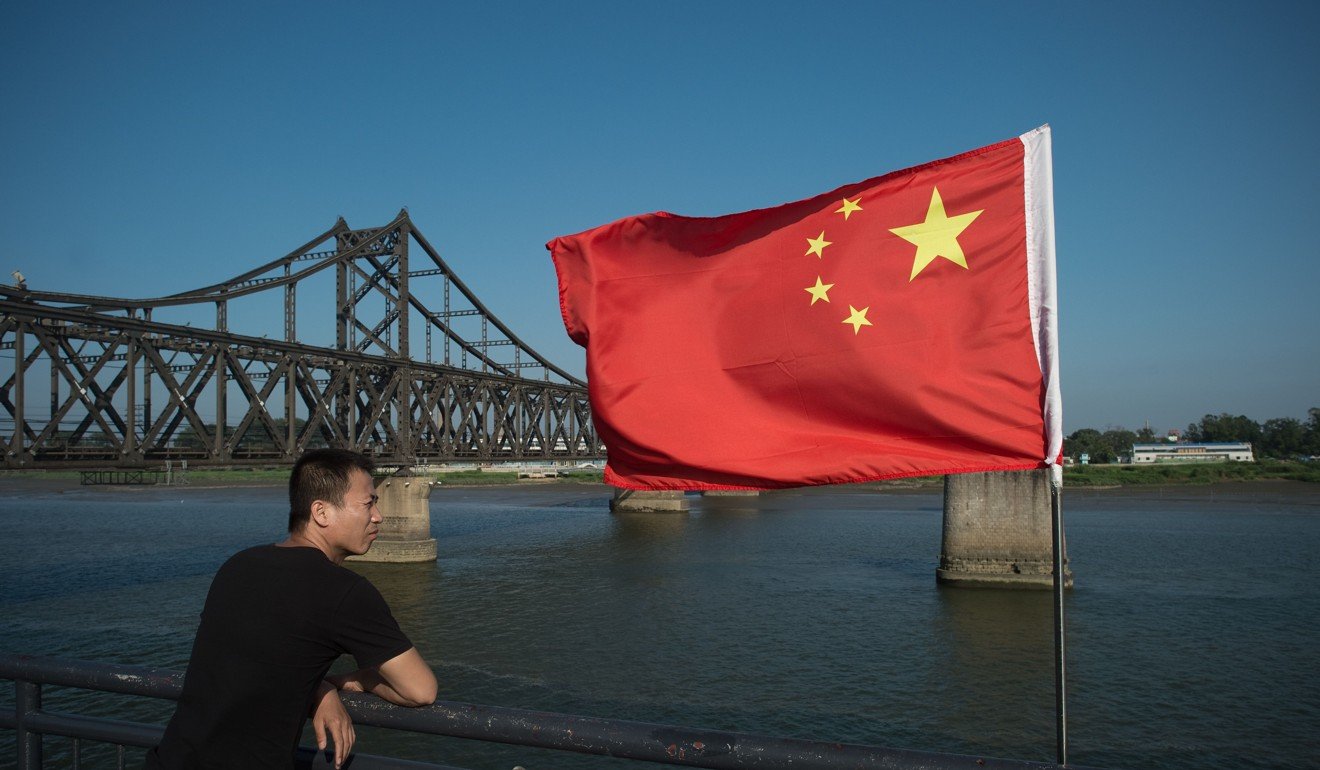

The incident in Hunchun aptly demonstrated the daily clash along the frontier between propaganda and reality, namely, China’s envisioning of the border as an arm of the “One Belt, One Road” dynamic. China’s international trade initiative is supposed to be indicative of its economic might, receptive to foreign trade and providing a new impetus or packaging for cross-border infrastructure. Adviser to the State Council, Liu Yanhua, visited the Quanhe customs house on August 10, talking up “One Belt One Road” even as he girded comrades, presumably, for the upcoming confrontation with upset seafood wholesalers.

In Jilin province’s easternmost city of Hunchun, “One Belt, One Road” investment has followed on from the “Greater Tumen Initiative” which envisaged the city as the de facto launch point for China’s ambitions for access to the Sea of Japan and to be the focal point in the region for trade with Russia. What has resulted is a big push for small factories in the textile sector in the city’s international cooperative trade zone and seafood processing facilities that have largely relied on North Korean labour and raw materials.

The new Security Council resolution does not force North Korean workers to go home and China refuses to recognise the “slave labour” label that EU countries and possibly the United States would like to place on North Korean workers in Hunchun and elsewhere. The number of North Korean workers in China, however, are not allowed to rise, a slightly odd concession by the China, scholar Justin Hastings notes, since no one has a clear estimate as to how many North Korean workers there are and the Chinese government has never announced any figures in the first place.

The North Korean government was in no mood to thank China for this at best foggy defence of Pyongyang’s business interests in northeast China. Instead, in a statement published on August 7, Pyongyang said that countries who had been tricked into voting along with the US for the resolution “would never be able to evade the responsibility for increasing the tensions on the Korean peninsula and jeopardising peace and security of the region”.

Other negative signs of poor relations have abounded. These have included rumours of North Korea’s pre-emptive closure of its own customs houses along the frontier to show displeasure with China, the new display of missile launches at an outdoor photo exhibition at the North Korean embassy in Beijing and a renewal of now perennial rumours that North Korean officials are privately telling cadres of their country’s glorious ability to target China with nuclear-tipped missiles. Xi Jinping’s meeting with the head of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, Genera Joseph Dunford, and the attendance of the American at some PLA military drills near Shenyang at the US request, also indicate a certain pique with Pyongyang.

At the end of the day, China’s long-term strategy remains incumbent upon the nurturing of an entrepreneurial class in North Korea and some form of free trade zones along the frontier.

Yet between Beijing and Pyongyang, there have been minimal direct statements of support for the other party, or even military to military contacts. A North Korean letter to the UN Secretary General decried US levying of “secondary sanctions” on Chinese firms doing business with North Korea as interference in China’s internal affairs. China’s protest against US-South Korean military drills this month falls in directly with Pyongyang’s national interest, as does the ongoing drumbeat against the deployment of a US-developed anti-missile shield in South Korea, even if that issue has taken on a life of its own.

Most significantly, rumours of a breakdown of military to military communication between Beijing and Pyongyang were proven false when Kang Sun-nam visited the Chinese embassy in North Korea last month and met with the Chinese ambassador and the PLA Defence attaché. Kang is hardly a “usual suspect” used to keep China at arm’s length, rather, he is a Korean People’s Army general appointed as a member of the Korean Workers’ Party Central Committee at the last party congress in May 2016.

Kang’s meeting with Beijing’s ambassador and military staff follows on from a meeting in February at the North Korean embassy in Beijing with Ci Guowei. Guo’s title is unwieldy (he is the vice-director of the Office of International Military Cooperation at the Central Military Commission), but his meeting with the North Koreans ought also to indicate that the two nations’ military to military relationship is not melting down in spite of Pyongyang’s missile launches.

China is playing a very delicate game at the moment. It has to keep the United States placated and supportive of its sanctions activity and certainly the “squid incident” at the Hunchun customs post moves the narrative in that direction.

Fortunately for Xi Jinping, Donald Trump’s core supporters are being fed a steady narrative that the US president’s pressure on China over the North Korea issue is working. Regardless of dissonance within the administration about the overall posture toward China, there appears to be an overall propensity and certainly a deep need in the Trump administration to portray China’s failure to abstain from, or veto, the latest UN sanctions as a major victory.

On the other hand, China has to keep North Korea’s political and military leadership from throwing their relationship to the four winds, conducting a new nuclear test, or sparking a broader war in the region. It will do so by trying to keep contacts broad if not deep with state actors in Pyongyang, keeping its intelligence edge with respect to North Korea, and not permanently cutting off the legs of Chinese traders (another good source of intelligence) who do business with North Korea. At the end of the day, China’s long-term strategy remains incumbent upon the nurturing of an entrepreneurial class in North Korea and some form of free trade zones along the frontier. A few truckfuls of spoiled seafood do not mark the end of that strategy, although if temperatures do not cool around the peninsula, the question of frozen squid as the new metaphor for Chinese-North Korean relations will be beyond irrelevant.

Adam Cathcart is a lecturer in Chinese history at the University of Leeds