How foreign authors are willing to bow to China's censors

Foreign writers who allow their books to be altered find results can be frustrating and time-consuming but extremely profitable

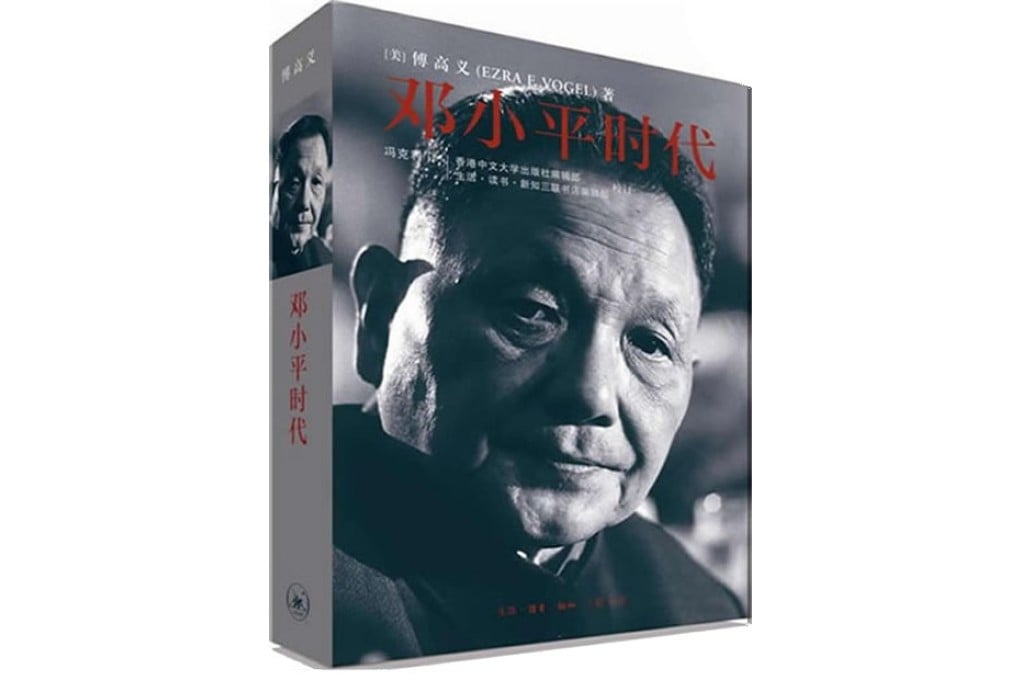

Chinese readers of Ezra Vogel's sprawling biography of China's reformist leader Deng Xiaoping may have missed a few details that appeared in the original English edition.

The Chinese version did not mention that Chinese newspapers had been ordered to ignore the communist implosion across Eastern Europe in the late 1980s. Nor that General Secretary Zhao Ziyang , purged during the Tiananmen Square crackdown, wept when he was placed under house arrest. Gone was the tense state dinner with the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev when Deng, preoccupied by the throngs of students then occupying the square, let a dumpling tumble from his chopsticks.

Vogel, a professor emeritus at Harvard, said the decision to allow Chinese censors to tinker with his work was an unpleasant but necessary bargain. His book, Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, sold 30,000 copies in the United States and 650,000 in China.

"To me the choice was easy," he said during a book tour of China through nearly a dozen cities. "I thought it was better to have 90 per cent of the book available here than zero."

With a highly literate population hungry for the works of foreign writers, China is an increasing source of revenue for American publishing houses; last year e-book earnings for American publishers from China grew by 56 per cent, according to the Association of American Publishers. Chinese publishing companies bought more than 16,000 titles from abroad in 2012, up from 1,664 in 1995.

Foreign writers who agree to submit their books to China's fickle censorship regime say the experience can be frustrating. Qiu Xiaolong, a St. Louis-based novelist whose mystery thrillers are set in Shanghai, said Chinese publishers who bought the first three books in his Inspector Chen series altered the identity of pivotal characters and rewrote plot lines they deemed unflattering to the Communist Party.

Qiu, who writes in English but was born and raised in China, said he reluctantly agreed to some of the alterations, but that others were made after he had approved what he thought were final translations. "Some of the changes are so ridiculous they made the book incoherent," he said. Having been burned three times, he said, he has refused to allow his fourth novel, A Case of Two Cities, to be printed in China.