Real or not, supernatural King Dangun is key to Koreas achieving unification dream

• Story of the founding monarch, son of a god and a bear, featured in recent diplomatic efforts between North and South

• Scholars say chances Dangun actually existed are close to zero but North Korea still claims to have found his tomb

It’s the stuff of an Indiana Jones film: supernatural kings, ancient tombs and government-backed archaeologists striving to harness the power of legend for a greater cause.

On a divided Korean peninsula, tales of King Dangun – the mythical founder of the first Korean kingdom more than 4,350 years ago – play a quiet but persistent role in keeping the dream of reunification alive.

This mythology made an appearance in September when North Korean leader Kim Jong-un took South Korean President Moon Jae-in to the top of Mount Paektu, the supposed birthplace of Dangun.

Moon also invoked the legend in an unprecedented speech in Pyongyang, calling for Korea to be reunited.

“We had lived together for 5,000 years but apart for just 70 years,” said Moon, whose parents came from what is now North Korea.

For many South Koreans, the idea of unification has become increasingly unrealistic amid a widening gulf between the two Koreas more than 70 years after they were partitioned in the wake of the second world war.

The legend of Dangun, however, plays a lasting role in promoting unification because it portrays Koreans as a homogenous group destined to live together, said Jeong Young-hun, a professor at Seoul’s Academy of Korean Studies.

“Dangun is a basis for Koreans to feel the necessity for pursuing harmony and unification,” he said. “Dangun is a basis for seeing unification as something possible.”

There’s little evidence for the glorious king or the thousands of years of Korean unity Dangun is said to have founded.

Still, that has not stopped North Korea from claiming to have found his tomb and South Korea from eulogising the unity of a kingdom that once challenged the might of China’s dynasties.

“In both Koreas, [Dangun] has been used to emphasise the uniqueness, the singularity, homogeneity and antiquity of the Korean people,” said Michael Seth, a professor of Korean history at James Madison University in Virginia. “Whether a real person or not, he is used by both Koreas to emphasise the unity as well as the uniqueness of the Korean people.”

Scholars say the chances that Dangun actually existed are close to zero.

According to Korean legend, Dangun was the son of a god who wanted to be a man, and a bear who wanted to be a woman.

“Dangun is a myth,” said Yeungnam University archaeologist Lee Chung Kyu.

North Korea’s founders originally disdained the story of Dangun as superstition incompatible with their ostensibly socialist ideology.

However, officials have since gone to great lengths to capitalise on the mythology and cement the ruling Kim family’s claim to Dangun’s legacy.

Official North Korean narratives have claimed Mount Paektu as the “sacred mountain of revolution” and assert that Kim Jong-un’s father, Kim Jong-il, was born on its slopes. Many historians place his actual birthplace in the former Soviet Union.

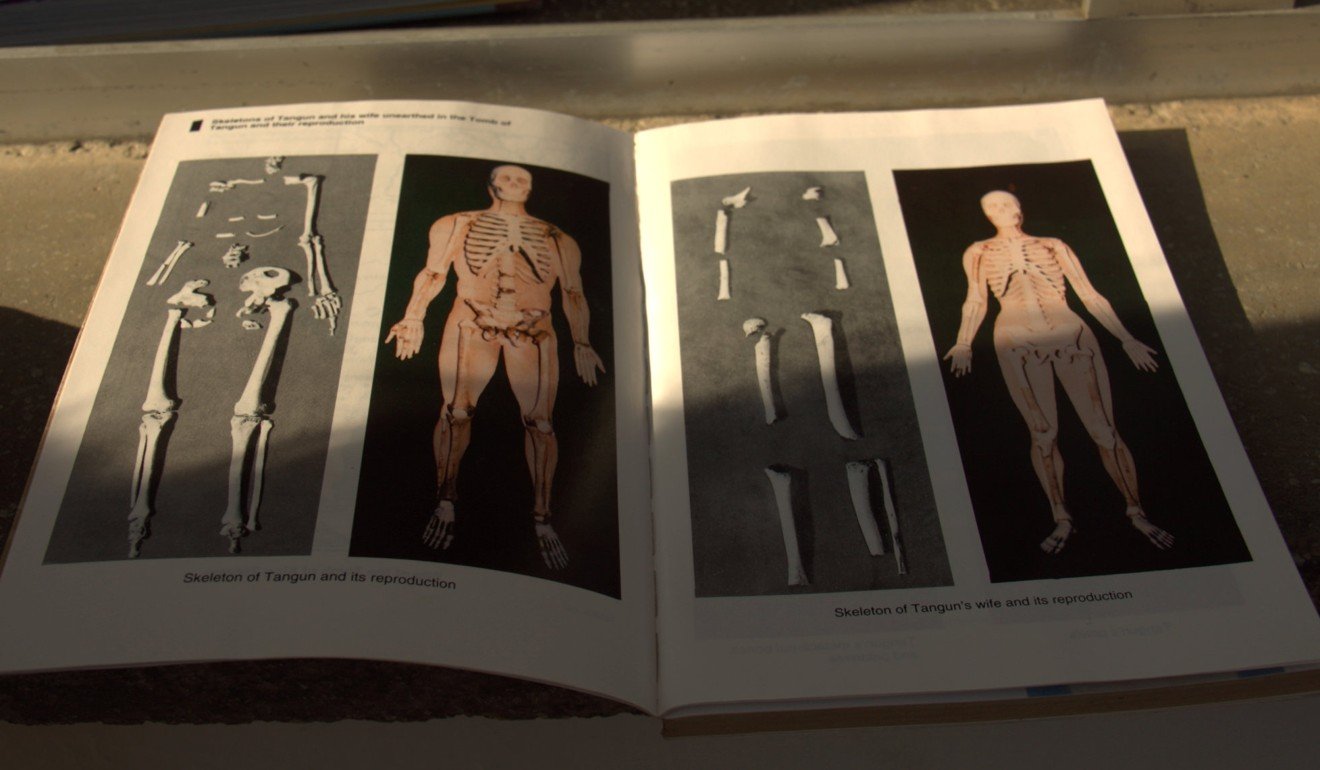

In the mid-1990s, North Korean authorities announced they had discovered the tomb of Dangun and his wife just outside Pyongyang, going so far as to “reconstruct” a white stone pyramid flanked by rough-hewn obelisks and statues of ancient princes and snarling beasts.

At the time, North Korean leader Kim Il-sung said constructing the mausoleum was designed to demonstrate “that Korea has a history spanning 5,000 years, that the Koreans are a homogeneous nation of the same blood since their emergence,” according to a state media article from 2015.

For about $115, tourists can peek inside a glass box containing what the North Koreans say are the bones of Dangun and his wife.

The high price and a reputation as an underwhelming experience mean few visitors pay to see the bones, Western tour guides say.

Amid a previous temporary thaw in relations between the two Koreas in 2007, a delegation led by South Korea’s defence minister visited Dangun’s royal tomb, and Pyongyang gave permission for South Korean tourists to visit Mount Paektu.

Unlike Dangun, there is more evidence for Gojoseon, the kingdom he purportedly founded.

Seoul’s National Museum of Korea has a display of bronze daggers, ceramics, and other relics said to be from the period and credited as “the first state ever to emerge on the Korean peninsula”.

Signs at the museum say Gojoseon lasted from 2,333 BCE to 108 BCE and “was powerful enough to compete as equals” with major dynasties in China. However, historians say details are disputed and have often been manipulated for political purposes.

“The early part of Gojoseon cannot be recognised as a state, especially not as a homogenous ethnic nation-state,” said Yeungnam University’s Lee, who argues the period was more likely marked by chiefdoms or tribes that only much later formed a more unified kingdom.

The idea of Dangun became especially popular among Koreans suffering under Japanese colonial occupation from 1910 to 1945, leading to the establishment of a home-grown religious movement that continues today.

The myth has sometimes been misused, leading to “chauvinism and extreme nationalism,” Lee said.

Still, Dangun makes his mark in both Koreas.

During the national Foundation Day holiday on October 3, hundreds of South Koreans gathered at shrines in Seoul to make offerings, wear masks depicting a bearded Dangun, and rally for a peaceful and united Korea.

On the same day in North Korea, senior unification officials visited the mausoleum to perform an “ancestral sacrifice for Dangun” and call for a unified Korea.

Jeong said the unifying themes of Dangun and Gojoseon are “imperative” as the two Koreas try to overcome their differences.

“The most important ground for justifying unification can be found in the idea that we are a homogeneous group bound together by a common destiny – that we have lived as one throughout history and we have to continue to do so in the future,” he said.