Sanctions fanning TB epidemic in North Korea, despite improved international ties

Aid organisations hit by economic measures against Pyongyang, meaning sufferers may spread their disease and die

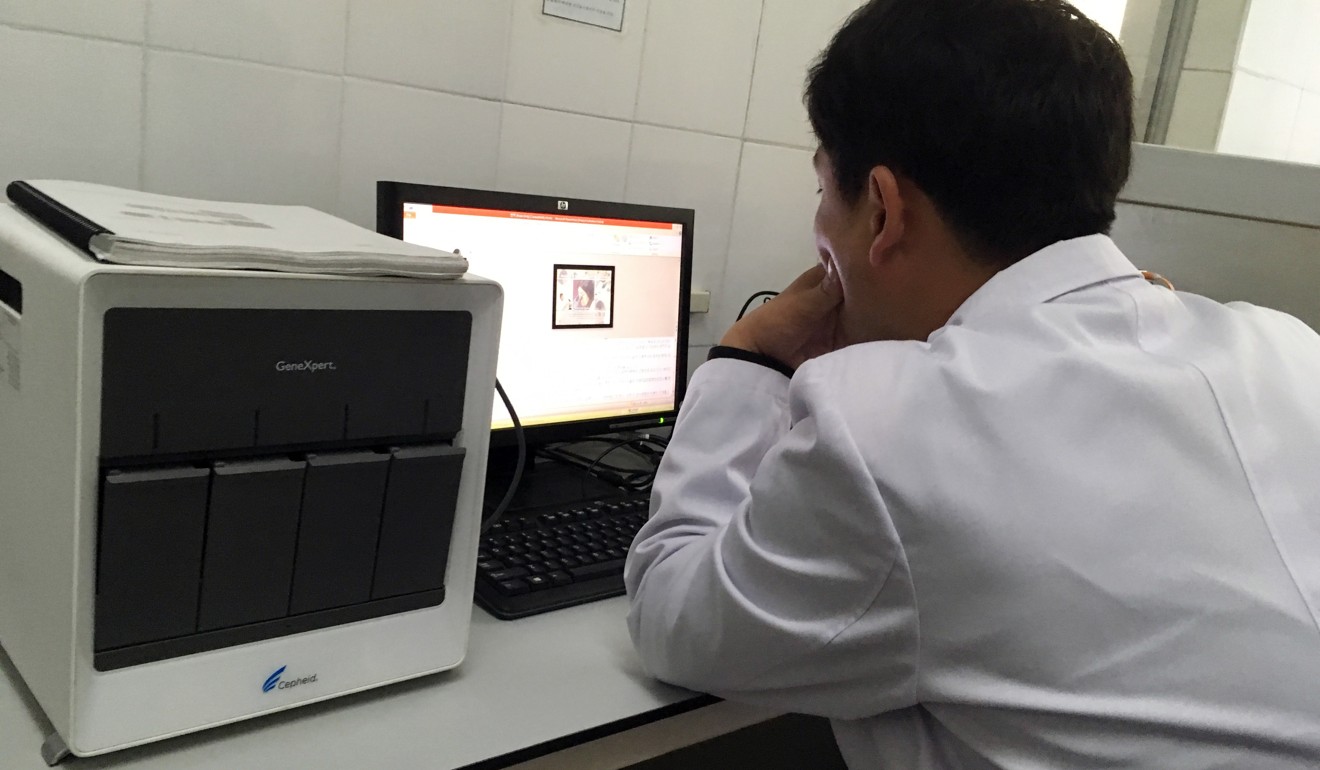

Dr O Yong-il swings open a glass door with an orange biohazard sign and points to the machine he hoped would revolutionise his life’s work. As chief of North Korea’s tuberculosis laboratory, O saw it as a godsend.

Tuberculosis is North Korea’s biggest public health problem. With the American-made GeneXpert, his lab would be able to complete a TB test in two hours instead of two months.

It took years, but O got the machines, only to discover GeneXpert needs cartridges he cannot replace. It’s not clear how they would violate sanctions imposed on North Korea because its nuclear programme, but no one, it seems, is willing to help him get them and risk angering Washington.

Despite budding detente on the Korean Peninsula since the summit between President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, sanctions championed by the US and Trump’s “maximum pressure” policy continue to generate hesitation and fear of even unintentional violations. That is keeping life-saving medicine and supplies from thousands of North Korean tuberculosis patients.

O’s laboratory, built with help from Stanford University and the Christian Friends of Korea aid group, has been running on empty since April. The idle GeneXperts may soon be the least of his troubles.

Two weeks ago, the Geneva-based Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria ended its North Korea-related grants, saying it could no longer accept the North’s “unique operating conditions”.

All the people that travel to North Korea, all the tourists, all the diplomats – they are a risk

The fund has dispersed more than US$100 million since 2010 to help North Korea control tuberculosis. Last year it supported the treatment of about 190,000 patients.

Spokesman Seth Faison said the fund is providing buffer stocks of medicines and health products until June next year. It welcomes the “positive diplomatic efforts” between Pyongyang and its neighbours, he said, but the fund’s position stands.

The decision shocked the doctors at the Pyongyang lab, who praised Global Fund for its past work but accused it of bowing to pressure from the US, one of its biggest donors.

The fund’s retreat sparked outrage outside North Korea as well. In a letter published in the medical journal Lancet, Harvard doctor Kee Park, director of North Korea programmes for the Korean American Association, warned the fund’s withdrawal could create a public health crisis and called the move “a cataclysmic betrayal” of the North Korean people.

If tuberculosis patients reduce or stop their medications early, or take lower-quality ones, the bacteria that cause the disease can develop resistance to the two most powerful anti-TB drugs, making the condition harder and more expensive to treat.

The Eugene Bell Foundation, which supports the treatment of more than 1,000 patients at 12 centres in North Korea, has been solely focused on fighting multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis since 2008.

What worries Stephen Linton, who founded the group in 1995, is what will happen to the patients who relied on Global Fund support. Many will die, but not before infecting others.

“This is an airborne infection,” he said. “Every time you are in a closed space with a TB patient, you are at risk. So for all the people that travel to North Korea, all the tourists, all the diplomats – they are a risk to everyone who comes near them.”

This was supposed to be the year Eugene Bell tripled to 3,000 the number of patients it treats.

The foundation has developed prefabricated wards for North Korean patients – semi-detached bungalows can be put up quickly by three or four people. The wards are paid for when they are shipped, so the money isn’t lining pockets of government officials or funding missile programmes.

Linton said everything was going well until December. A pilot project with 10 wards is operating on the outskirts of Pyongyang.

“Then we ran into this sanctions problem,” he said. “It’s not that we cannot send anything in. But these buildings have a metal roof – a panel that has metal in it, aluminium – and that’s the issue.”

Linton said Eugene Bell has US$250,000 of prefabricated wards rotting in a dockyard outside Seoul.

“Unless something is done and done soon, this medical emergency will become known in Korea as the ‘Sanctions TB Epidemic’,” he said. “And it will haunt the peninsula for generations.”