They’re cute and cuddly, but will Japan’s Olympic mascots become cash cows?

They are wide-eyed, brightly coloured, and completely adorable. But can Japan’s Olympic mascots bring in the cash, in a country where cuddly icons promote everything from regional tourism to local prisons?

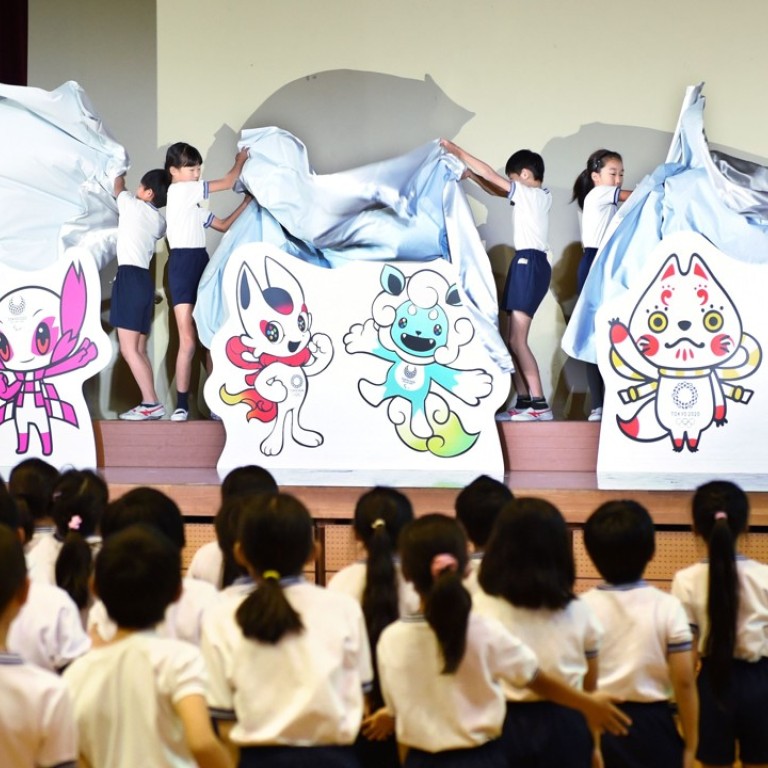

Japan unveiled three sets of prospective mascots for the 2020 games last year. The winning duo will be announced in February, graduating into a landscape packed with cute and quirky characters.

Known locally as “yuru-kyara” or “laid-back characters”, mascots can be major money spinners.

The pot-bellied, red-cheeked bear known as Kumamon – created in 2010 to promote Japan’s southern Kumamoto region – raked in US$8.8 million last year for local businesses selling branded products.

Mascots capitalise on a local love of all things adorable, including characters that have gained international fame like the perky-eared yellow Pokemon, and the demure Hello Kitty with her signature hair bow.

“Japan has a tradition of creating personalised characters out of nature – mountains, rivers, animals and plants,” said Sadashige Aoki, professor of advertisement theory at Hosei University.

“It has a tradition of animism, a belief that every natural thing has a soul.”

Now the hope is that the Tokyo Olympics mascots can serve as both ambassadors for Japan’s expanding tourism industry, and a way to recoup some of the billions spent on staging the Games.

“It’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance for Japan to promote its tradition, culture and how its society looks,” said Aoki. “The question is how to make them globally popular, like Mickey Mouse.”

In the past, Olympic mascots have been anything but a sure bet in terms of revenue.

Brazil netted US$300 million in profits from licensing intellectual property from the 2016 Games, according to the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

Merchandise featuring Rio’s feline mascot Vinicius was the top-selling item.

But Wenlock and Mandeville, the widely mocked mascots of the 2012 London Games, proved far from Olympic gold.

The one-eyed characters were dubbed “bizarre” and “creepy” by some, reportedly sending shares in their manufacturer down by more than a third.

Without the cute factor, mascots are unlikely to have much success, said Munehiko Harada, professor of sports business at Waseda University.

“It’s important that mascots are popular among children,” he said.

But even if the mascots have mass appeal, they may not be long-term moneymakers for Japan because of licensing issues.

“Olympic mascots in the past have been forgotten after the Games were over,” said Harada. “But there is a chance they remain alive and remembered as a legacy of the Tokyo Olympics, depending on how they operate the business.”

Tokyo 2020 owns the intellectual property rights to the mascots for now, but will have to transfer them to the IOC and the International Paralympics Committee after the Games.

“If I were head of the Tokyo 2020 organising committee, I would demand the IOC loosen its control over rights,” Harada said.

Without those rights, there will be no way to capitalise on the mascots after the Games, including developing backstories that drive ongoing interest.

There has been no indication so far that Japan intends to request rights to the mascots, with a spokeswoman for Tokyo 2020 confirming that it expects to relinquish them after the Games.

But the organisers say they are still expecting a substantial windfall from the mascots and other merchandise and licensing opportunities.

“Of the total revenues, US$130 million is forecasted to accrue from licensing” of mascots and other Olympic emblems, a Tokyo 2020 official said. “While we have the target number, we aim to increase it.”

The money is desperately needed, with officials drawing criticism for the massive cost of the Games.

Japan has already slashed the Tokyo 2020 budget by US$1.4 billion, but is under pressure to further reduce the US$12.6-billion bill.

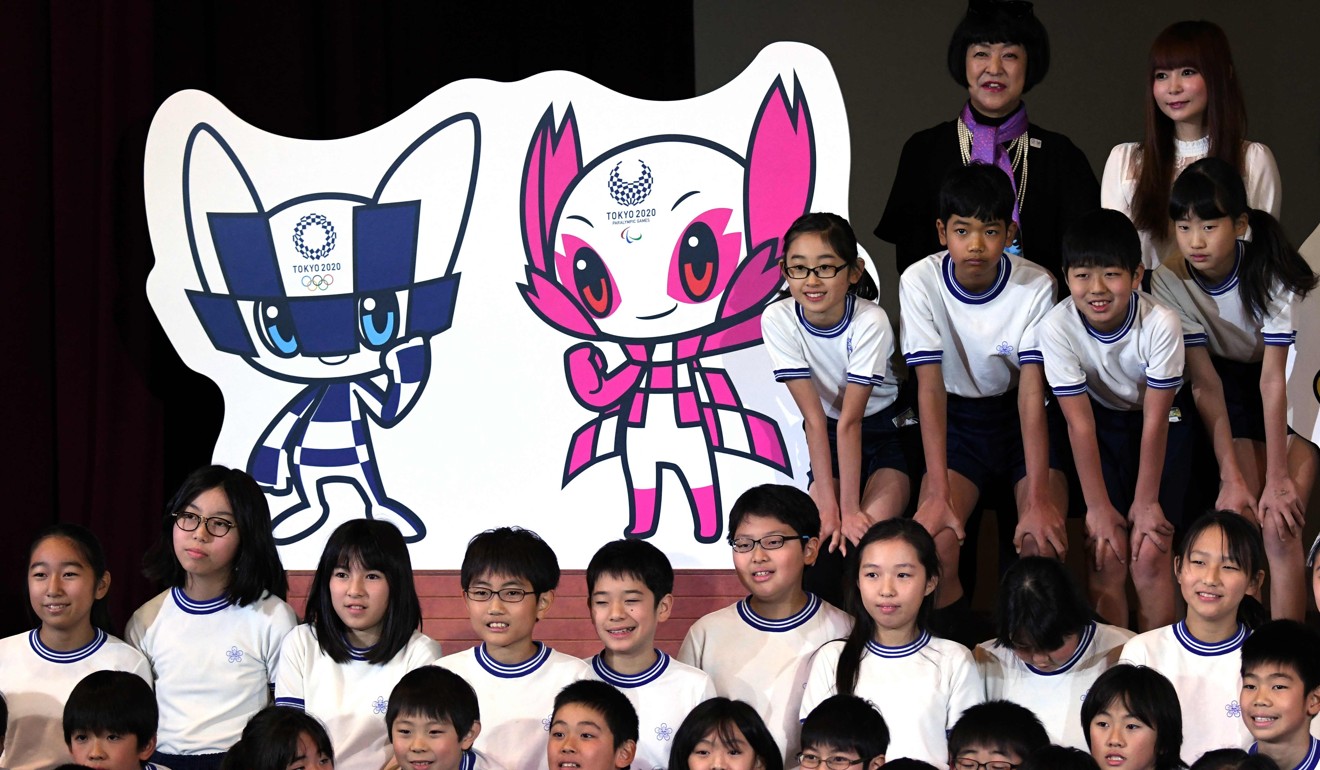

Children will decide which pair of characters will represent the Olympics. They are voting in schools across the country, with the results to be announced on February 28.

At one school in northern Tokyo, delegates proudly dropped the names of the winners of each class’s vote into a ballot box.

There was little love there for category C: a fox wearing ancient beads and a slightly bemused-looking red raccoon. The pair failed to get a single vote.

Also left behind was category B: a hybrid of a lucky cat and a fox, and a blue lion-dog of the type seen guarding Japanese shrines. They managed just five votes.

The clear winner, with 14 votes, was category A’s sleek, manga-inspired duo, with their pointy ears, oversized eyes and bold chequered uniforms.

“As soon as I saw pair A, I made my choice,” said 10-year-old Taiki. “They are cool. They are far ahead, I think they will win.”

.png?itok=arIb17P0)