World capital of tapestry, France’s Aubusson is a quaint, quiet peek into the past

Nestled in the heart of rural France, the traditions and trade of a medieval craft are alive and kicking

“You become mesmerised by the work and transported to another place of calm,” says France-Odile Perrin-Crinière. “It’s like a meditation.”

A weaver for 30 years, Perrin-Crinière runs the Atelier A2 workshop, in the narrow main street of Aubusson, a small town in the heart of rural France that revels in the title of “the world capital of tapestry”. Next door is an old wrought-iron market hall that is now half antiques store, half charcuterie – aromatic sausages vying for pride of place with musty furniture.

Slip through an archway next to A2 and along a time-worn alley and you come to the River Creuse, a gurgling stream of cola-brown water that is part of the tapestry story. The Creuse is acidic and its water is good for degreasing wool and fixing dyes. Along with the local sheep-farming, it was factors such as this that first brought weavers to Aubusson, in the 14th century.

Stroll past old grey-stone houses facing the river, cross a bridge and you come to the Manufacture St Jean. The oldest tapestry maker in town, set up in the 17th century, St Jean’s stock room is a riot of colour, its shelves crammed with skeins of wool of every possible hue alongside multicoloured bobbins of silk arranged in racks. A treat at St Jean (at least until the end of October) is an exhibition room lined with the big – about three by two metres – brightly coloured tapestries of Jean Lurçat, full of stylised creatures, especially cockerels. A pivotal figure in the history of the art form, this painter came to Aubusson in 1937 and began designing modern-art tapestries. They sold well and the then moribund craft revived, with many more artists joining the trade.

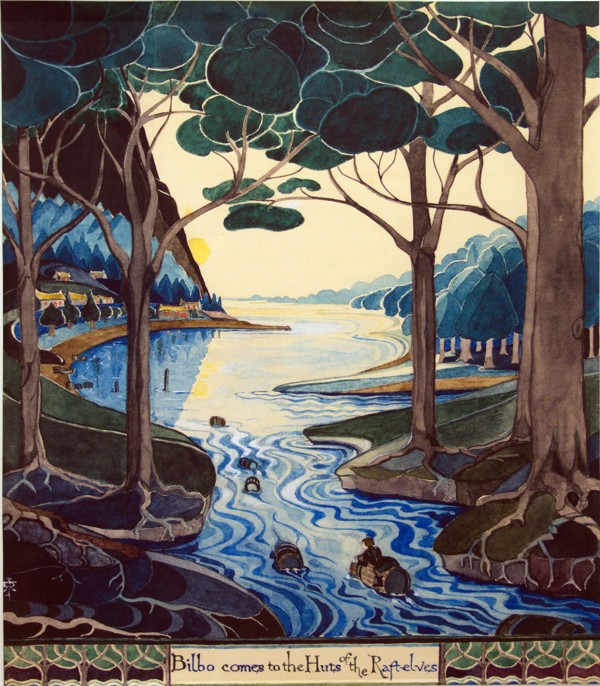

Walk around the corner and there, on a rise, stands the Cité Internationale de la Tapisserie Aubusson, an op-art facade of polychrome vertical stripes. Opened in 2016, the Cité is a resource centre boasting a display of tapestries dating from the 15th to the 21st centuries, and (until September 18) an exhibition of huge drawings for a series of tapestries based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s own illustrations for The Lord of the Rings (1954) and The Hobbit (1937).

For a weaving demonstration, track back over the river, up narrow, cobbled Rue Vieille and into a curious old building with a turret on its corner: the Weaver’s House.

Back in the main street is the art-deco swagger of the town hall, the grand foyer of which hosts the biggest tapestry in Aubusson, a passionate work depicting the fierce weaving contest between Pallas and Arachne in Greek mythology.

Close to where the main street crosses the Creuse is surely Aubusson’s prettiest view, that from the little Terrade Bridge, flanked by old half-timbered houses. In one of them, Chantal Chirac welcomes visitors to her Cartoon Museum. The Parisian antiquarian came on a visit in 1990 and never left.

“I saw many beautiful old cartoons lying around,” she recalls, “and I decided to move here and make a business of restoring them.” She shows visitors around on most afternoons and explains the craft of cartoon-making with the help of some gorgeous examples.

At the Atelier de la Lune (“moon studio”), Nadia Petkovic is also happy to chat, as she busily weaves a tapestry in a series that depicts the four elements, designed by painter Daniel Riberzani.

“I got stressed out as a big city art teacher, and found my true métier here,” says Petkovic, another Parisian who has found sanctuary and opportunity in Aubusson’s provincial calm.

The area has six small workshops with independent weavers such as Petkovic and three “manufactures”, factories that complete the tapestry-making process – designing, dyeing, weaving, hanging – and make carpets.

Also in Felletin is the Terrade wool mill, where visitors can get down and dirty with the business of wool processing. Most of the wool now used is merino, from Australia, rather than local varieties, because merino yarn is finer and better suited to tapestry weaving. Piles of the tangled grey stuff wait to be fed into long banks of machinery that clank and whir.

At the top of the village hill is Felletin’s 15th-century church, now a cavernous exhibition space. On show here until November 4 are dazzling modern tapestries designed by the painter Mario Prassinos, whose name seems familiar. Then it dawns on me; it’s written on a guest room door at my hotel, the Hotel Le France, in Aubusson’s main street. The hitherto puzzling names on the doors must be those of tapestry artists.

“I’ve already got a cartoon to go behind the bed there,” he says, as we bound into the Jean Arp room.

Tapestries for sale line the hotel’s traditionally styled restaurant.

A short walk from the hotel, down by the river, Thierry Roger runs a one-man dyeing workshop. In a singlet and tattered jeans, the grizzled Roger sweats over a steel vat, dunking long skeins of wool into boiling acidic water, adding powder dyes periodically.

Like so many of Aubusson’s artisans, Roger is absorbed by his work and is happy in his hometown.

“I don’t travel,” he grins.

Stay a few days in Aubusson and you can understand why, as you slow to the pace of la France profonde.