How Hong Kong buildings kept cool before air conditioning by copying India – deep verandas, high ceilings, chick blinds and shutters

- Lying on almost the same latitude and with similar climatic conditions, Calcutta, and other buildings in Bengal, inspired many building features in Hong Kong

- Calcutta was also the major external trading partner for the Canton delta, and for a cosmopolitan array of merchants, constant travel there made for familiarity

Sustainability has become a buzzword in recent years and more-form-than-substance “green initiatives” inevitably lead to accusations of “greenwashing”. But how did buildings in the past help define an earlier era’s notions of practical sustainability?

Above all else, the aim in Hong Kong and elsewhere in maritime Asia was to keep a building’s occupants sustainably cool – and therefore healthy, a vital consideration in the disease-prone tropics – in the days before mechanical cooling methods, such as electric fans, were invented, and widely introduced. Air conditioning – and the far-reaching transformations that invention brought – was another century away.

In newly established cities, such as 1840s Hong Kong, practical examples from elsewhere were readily copied. After all, why reinvent the wheel? Surprising as it may seem to many today, the architectural exemplar for early Hong Kong was Calcutta, and buildings elsewhere in Bengal.

The reasons were manifold, and fundamentally practical; Calcutta – then – was the major external trading partner for the Canton delta, and for a cosmopolitan array of merchants, constant travel there made for familiarity.

Both cities lie on almost the same latitude, thus climatic conditions are similar: a cool, dry few months in the winter, with a brief period when both places are actually cold, followed by several months of scorching heat, high humidity, fairly heavy, regular rainfall, and intermittent tropical depressions in the summer – known as cyclones in the Bay of Bengal, and typhoons in East Asia.

Hong Kong’s earliest British-era buildings – especially those constructed and used by the armed forces – borrowed practical environmental features that can be found to this day in any military cantonment area across India from Meerut to Bangalore.

Having your photo taken by this man was quite the Hong Kong status marker

Deep verandas, pitched and angled to keep direct sunlight away from interior walls, provided nearly year-round outdoor living space; it was not uncommon for these open spaces to double up as sleeping areas during the hottest nights.

Verandas generally had chick blinds, made of thin wooden slats or (more usually) split bamboo, that could be extended from ceiling to floor to keep out the sun. Often lined on the inside with canvas cloth, which provided further protection against the sun’s rays, chicks could also be kept wet with regular sprays of water.

The resultant evaporation, hopefully combined with a breeze, further cooled the shaded area, but inevitably added to general ambient humidity within a confined space.

Thick walls were significantly cooler – as well as structurally sturdier in monsoon climates – than thin ones. Open fretted panels above interior doors allowed breezes to circulate through rooms, even when the doors were closed for privacy. Shutters on the outside of windows, with adjustable slats, allowed air to filter through, while at the same time minimising direct exposure to sunlight – or prying eyes.

As well as providing a welcome sense of spaciousness, high ceilings allowed a room’s heat to percolate upwards and through fretwork vents into the roof cavity and then outside. Fireplaces and chimneys did double duty, providing warmth during the months when a fire was welcome, and then as a hypocaust during the hot weather, to help encourage draughts and wick out accumulated heat.

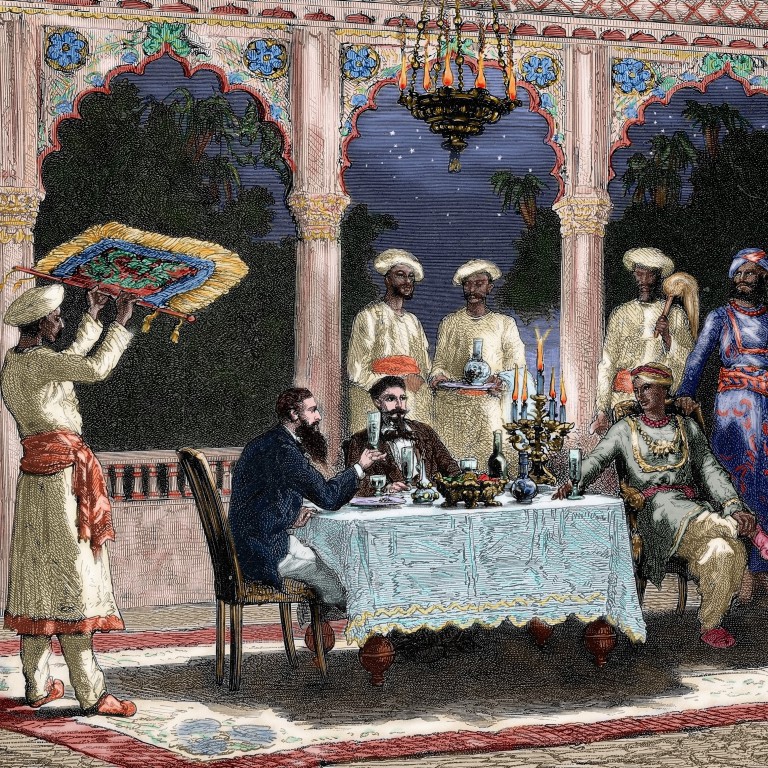

Punkahs were also deployed; these primitive fans – the Hindi word entered local lexicons across Asia from the 18th century – were basically reinforced, stiffened large flat surfaces, which could be made of anything from thick fabric to woven rattan.

The punkah was attached to the ceiling and connected to a rope-and-pulley mechanism, which, when repetitively pulled by hand by a punkah-wallah, allowed the “fan” to flap back and forth, providing some kind of primitive breeze. Each such innovation helped to make tropical life just that little more comfortable.