How Chinese influenced, and was influenced by, other Asian languages

- About 60 per cent of the words in the Japanese and Korean languages have Chinese origins

- Over the millennia, the Chinese language has absorbed foreign words in five waves, the last of which is still ongoing

At a recent dinner party – the size of which conformed to the numbers allowed that week – a guest dismissed her country’s national language as “not a real language” because it contained many words borrowed from the language of another land. Her attitude, which surprised me, might have been informed by being forced to use a national language at school, rather than the vernacular that she, a member of an ethnic minority group, spoke at home with her family. While I am sympathetic to those who are forced to learn in an unfamiliar tongue, I do not agree that foreign loanwords make any language less “real”.

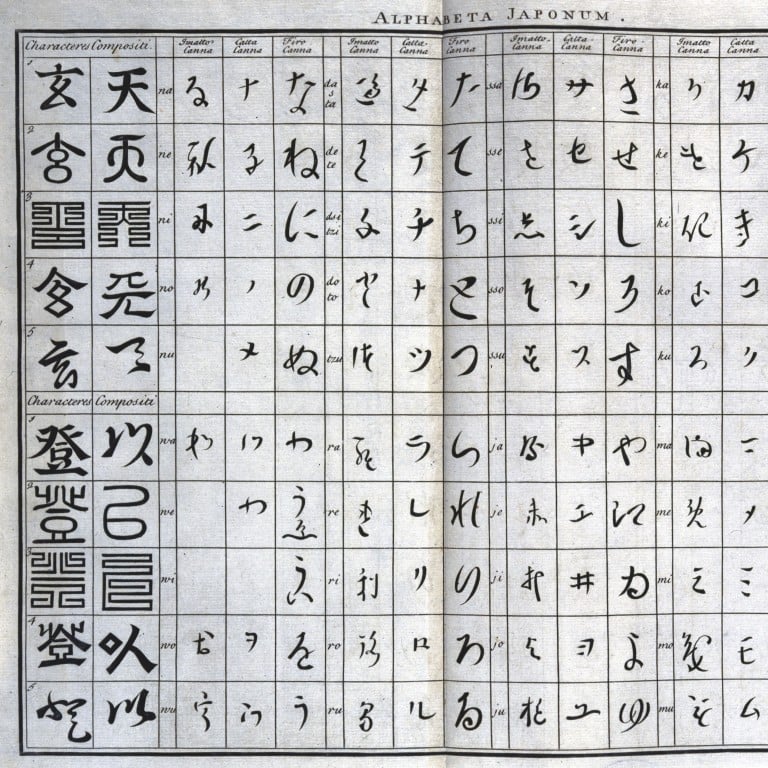

In a modern Japanese dictionary, around 60 per cent of the entries are kango, literally “Chinese words”, which originated in Chinese or were created from its linguistic elements. Hanja-eo, or Korean words of Chinese origin, account for almost 60 per cent of all Korean vocabulary. Modern Vietnamese features a large Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary, or tu han viet, ranging from one- to two-thirds of any discourse depending on context and the degree of formality.

It would be absurd to suggest Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese are not “real languages” because large portions of their lexicons originated in Chinese. We have not even included the many loanwords from European languages, especially English, which have been incorporated in recent times. The Chinese language – historically the major source of words for several Asian languages and to a lesser extent European languages (tea, to lose face) – is itself a borrower of foreign words and expressions.

Foreign loanwords arrived in China in at least five different waves. The first two, during the 2nd century and the Sui and Tang periods (581-907), coincided with the introduction of Buddhism from the Indian subcontinent and its proliferation in China. Many Buddhist texts were translated from Sanskrit to Chinese, especially in the Tang dynasty, which brought words of Indian origin into China’s lexical orbit.

Why it’s hard to argue there is one Chinese language

The third wave occurred during the trading boom in the Song period (960-1279), when China conducted high volumes of maritime trade with Southeast Asia and the littoral nations of the Indian Ocean. The next wave of loanwords arrived with European Catholic missionaries in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), while the ongoing fifth wave, from the late 19th century to the present, has seen the biggest influx of foreign words.

The Chinese language absorbs foreign words in several ways. Many loanwords are phonetically transcribed into Chinese, such as chana (“a brief moment” from the Sanskrit ksana), binlang (from the Malay pinang, or “betel nut”), youmo (from the English “humour”) and haike or heike (“hacker”).

Other loanwords are semantically translated from their original language, like regou (literally “hot dog” in Mandarin), lantu (literally “blue print”) and xiangyata (“ivory tower”). There is also a blending of both methods, e.g. baleiwu (“ballet”), where balei is a transcription of “ballet” and wu is the native Chinese word for dance.

In the last century, there has been a “reverse borrowing” from Japanese. Words coined by the Japanese using Chinese characters, especially those that refer to modern concepts, were incorporated into the Chinese vocabulary, such as the words minzhu (“democracy” from the Japanese minshu), kexue (“science” from kagaku). More recently, Japanese popular culture has had a profound influence on Chinese. Words like renqi (“popular” from ninki) and zhai (“geek” from otaku) are now used by Chinese all over the world.

Languages, and their speakers, are neither inherently superior nor inferior, whether they are sources or receivers of loanwords. Rather, the existence of these words in almost all languages speaks of the beauty of human interaction throughout our history.