The passport that was lifeline for refugee Jews and White Russians who fled to China and Hong Kong

The Nansen passport – named after a Norwegian Nobel laureate – allowed those left stateless after the first world war to escape, including famous names such as Marc Chagall, Anna Pavlova and Aristotle Onassis

Contemporary Hong Kong has numerous asylum seekers, as refugees or displaced persons are now described. While their individual claims are being processed – a laborious bureaucratic exercise that usually leaves these unfortunate people in limbo for years – travel and other identity documents are required. These days internationally recognised identity documents are issued by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. But how did refugees without valid papers travel in earlier times?

In the wake of the first world war, international borders in Europe were dramatically redrawn as long-established political entities, such as the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, disintegrated into nation-states that coagulated mostly along ethno-linguistic lines. Millions of displaced persons surged across new borders throughout Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans. Others – trapped in the ghastly aftermath of war and political chaos – found themselves fleeing for their lives.

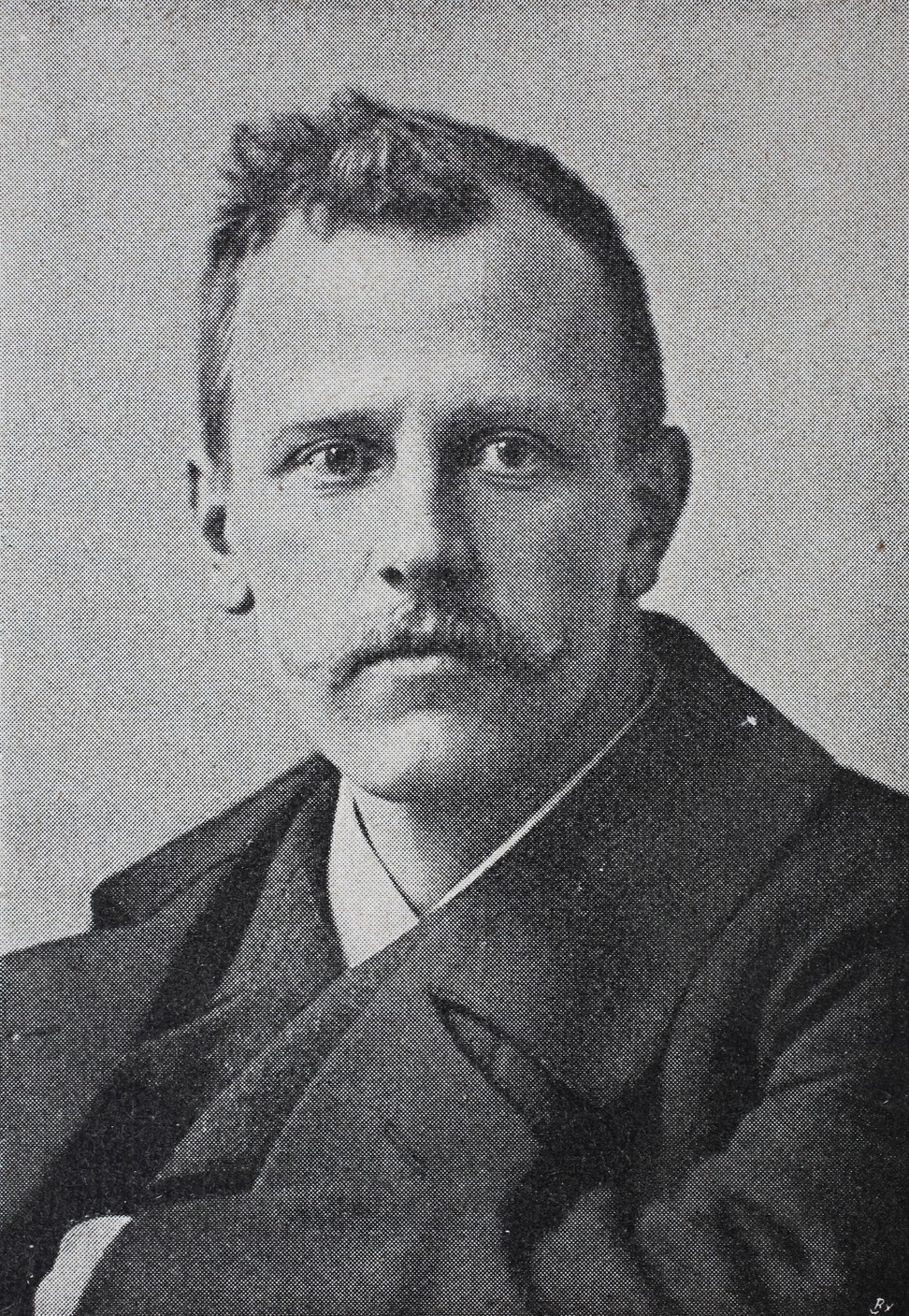

The League of Nations, formed in 1920, issued travel documents for those refugees with no claim on alternative citizenship through place of birth, marriage or descent. Known as Nansen passports, these documents were named after renowned Norwegian polar explorer, politician and humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen. Famous during his lifetime, though today largely forgotten outside Scandinavia, Nansen became involved in the plight of refugees in the aftermath of the first world war and worked tirelessly to assist them.

He regarded refugees as “citizens of the world” to be helped, rather than an unwelcome burden on the countries to which they fled.

The travel document Nansen helped establish was eventually named in his honour. For his work on behalf of displaced persons, Nansen was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922. After his death, in 1930, the League of Nations established the Nansen International Office For Refugees to continue the initiatives he had begun. This organisation was awarded its own Nobel Peace Prize, in 1938.

Nansen passports were also issued to those who had been stripped of their citizenship by discriminatory laws. In particular, German Jews who had left the country in the mid-30s, while they were still able to do so, were then deemed stateless by the Nazi regime, and subsequently travelled on Nansen passports. Many German and Austrian Jews ended up in Shanghai in the late 30s, the International Settlement there being one of the few places in the world where an entry visa was not required.

Nansen passports were issued from 1922 until 1938. More than 50 countries recognised them as valid travel documents and, while most holders were ordinary displaced persons, various internationally known figures travelled using a Nansen passport at some point during their life; among them were painter Marc Chagall, ballerina Anna Pavlova and shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis.

Between the wars, numerous stateless persons entered Hong Kong using Nansen passports. Many subsequently acquired another nationality, through marriage or onward emigration. Before changes in the British Nationality Act, which began in 1962, holders who had lived in Hong Kong long enough were able to apply for naturalisation as a British subject. Others – mostly White Russians – eventually emigrated to destinations such as Australia or the United States.