How Hong Kong’s Kowloon Park got its name, despite public pressure to call it Sun Yat-sen Garden

The green heart of Tsim Sha Tsui was built at the site of the former Whitfield Barracks

“Wanted … a name for a park”, ran a headline in the South China Morning Post on September 13, 1968.

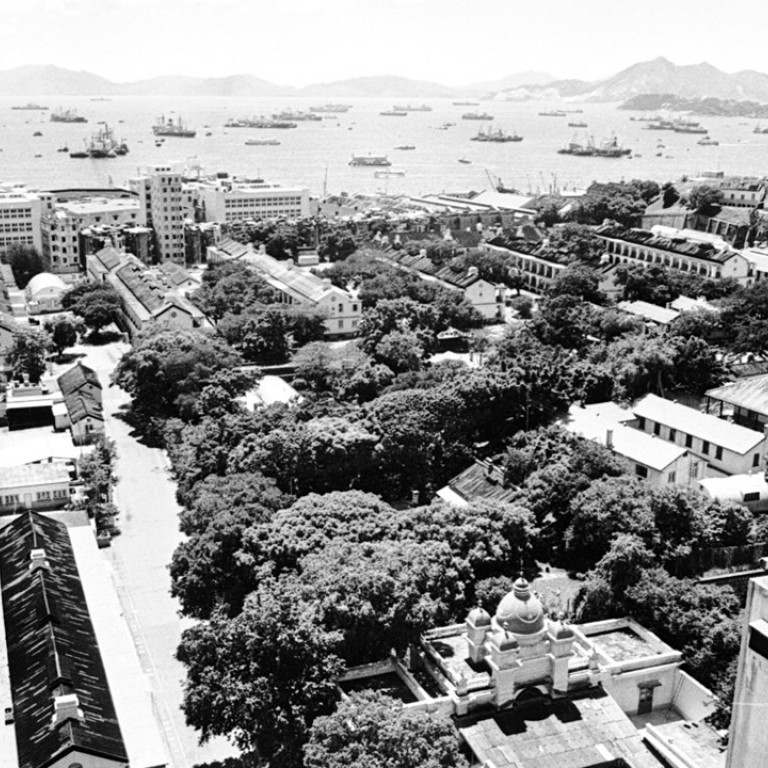

The story followed the Post’s initial report, five years earlier, on November 27, 1963, of a proposal to “develop the 42-acre Whitfield Barracks area in Tsimshatsui, Kowloon, as a large public park with commercial and residential building sites” following the War Department’s decision to “surrender” the site where army boots had stomped for more than a century.

On April 5, 1967, the Post had followed up by reporting the Urban Council’s support for calls for the government to “ignore purely commercial considerations for development of the […] site and turn over the whole area for public park and recreation”. It was observed that “Hongkong’s development to 1,000 acres of open space – or about ten square feet for each person – still left it very low, compared with the provision of other much older cities.”

On November 4, 1968, the Post reported that “One hundred and fifty organisations representing more than 500,000 people have sent a joint letter urging the government to consider naming the new park in the Whitfield Barracks ‘Chung Shan Garden’ or ‘Sun Yat-sen Garden’.” The Sun Yat-sen Memorial Association of Hong Kong was quoted as saying that it would be “a worthwhile gesture for the government to name the park after one of the greatest men in the East”. But the following day, the Post reported the council’s more prosaic choice, Kowloon Park.

Controversy over the name rumbled on but the association’s demands to know why the government had “ignored the public’s view” went unanswered.

The park was officially opened on June 24, 1970, by governor Sir David Trench, who, along with distinguished guests, watched a northern-style lion dance and looked on as primary school pupils performed a folk dance.

Trench described the new facility as “perhaps the closest approach we have in Hongkong to a traditional landscaped English park”. And then it rained.