- It’s Christmas Eve in Shanghai in 1930 and a mysterious guest has accepted an invitation to the Carmichaels’ annual drinks party. Soon a gunshot rings out …

Christmas Eve at the Gascoigne Apartments was always a special time and December 24, 1930, was expected to be the same as usual.

The Gascoigne wasn’t the largest apartment building in Shanghai’s Frenchtown, or even the most impressive on the wide boulevard of Avenue Joffre. But it always stood out at Christmas time with coloured lights hung over the entrance and candlelit Chinese lanterns in every window.

The residents of the Gascoigne’s five apartments each celebrated the festive season in their own way, giving the entire building a cosmopolitan atmosphere.

Above the lobby, on the first floor, lived the Carmichaels, a septuagenarian Scottish couple. Roger had been a Yangtze steamship captain; Edith spent decades as his patient wife. At Christmas they decorated their apartment in a manner one might associate more with Dickens than the Gascoigne’s modern art deco.

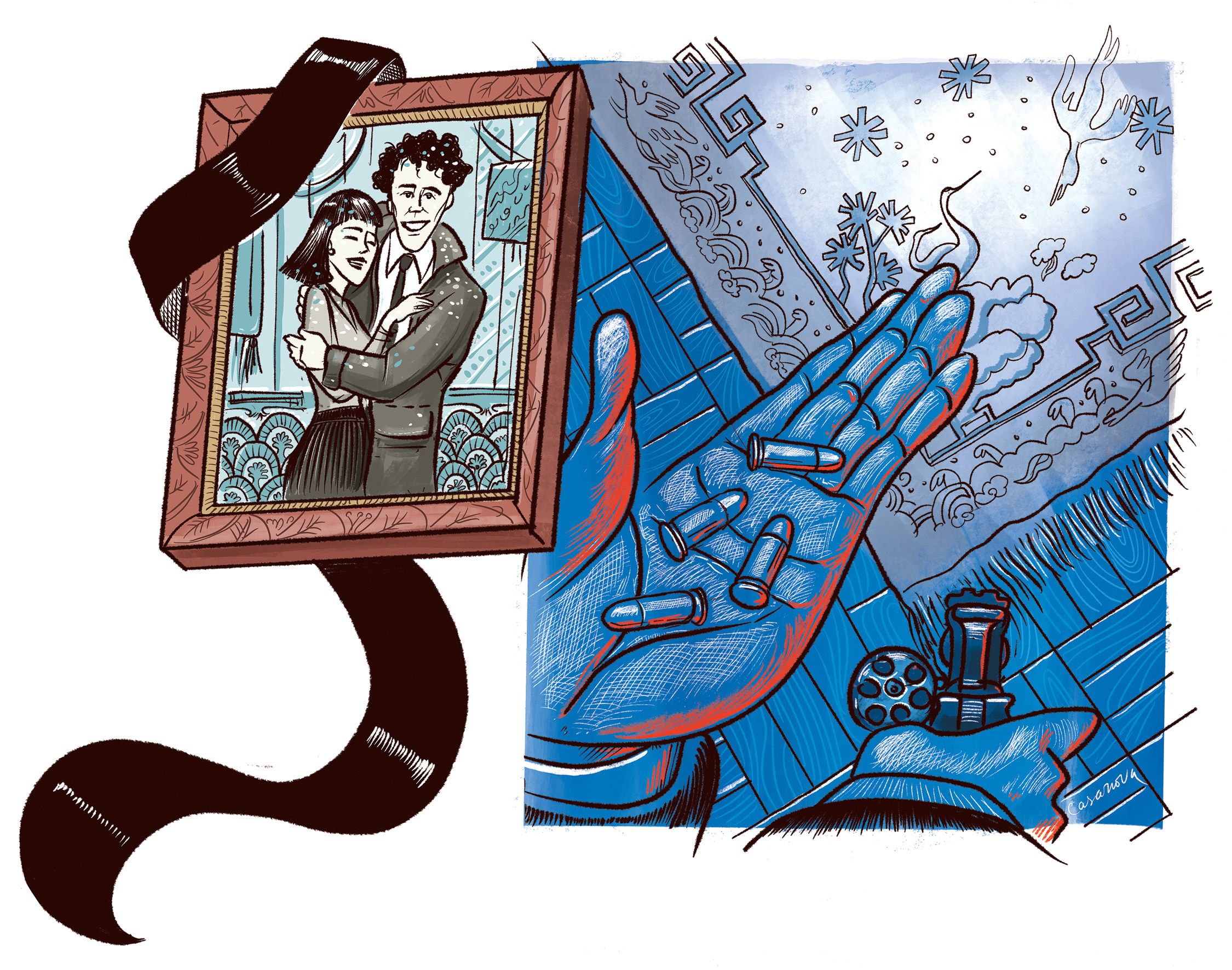

Having been a seafaring man there was invariably something of a nautical theme – three ships a sailing in was usually prominent. However, though they tried to be as festive as possible hosting an annual Christmas Eve drinks party for all their fellow residents, you couldn’t help but notice the photograph of a young man and woman, in smart clothes, with what looked like confetti in their hair, prominently displayed on their marble mantelpiece and, every year, at this time, the picture was draped with black ribbon.

Opposite the Carmichaels on the first floor lived the Bakers, who were American. Ulysses was in shipbroking and had done well for himself. His wife, Fiona, was famously extravagant in their Christmas decorations but, since they’d moved in, was too afraid of the outside streets to ever leave the Gascoigne.

The Carmichaels and the Bakers knew each other, acknowledged each other cordially when they met on the landing or stairs, but only ever socialised once a year, on Christmas Eve, at the Carmichaels’ party.

Above, on the second floor, lived the Lobchenkos, Russian émigrés, and their apartment was stuffed with tsarist-era furniture they’d brought all the way from Sverdlovsk in 1919.

Alexander and Yulia Lobchenko were elderly now and, despite their carefree earlier days having been torn away from them, they had made a new life in Shanghai. But, like the Carmichaels below, their Christmas joy was tempered by having lost their only child, Anastasia, when she was still young.

Like the Carmichaels, they had never gotten over the loss.

Opposite the Lobchenkos lived the Dumonts, originally from Rouen. The French couple had run a jewellers on Nanking Road for many years before they sold up and retired. Every Christmas they strung up a sign on their door proclaiming “Joyeux Noel”.

Festive fiction: Murder on the Shanghai Express – a Christmas whodunit

The Gascoigne’s lobby was overseen by a Chinese concierge, known to everyone as Mr Shu. He spent his days behind a large desk watching the street outside. He received deliveries, post, and would dash around his desk to open the front door for residents, hail taxicabs or rickshaws, and generally see to their every need.

Though in his 60s, Mr Shu always helped Edith Carmichael carry her parcels up to her apartment; he ensured Mr Dumont’s monthly wine delivery was safe and stored away to avoid breakages; arranged a taxi when Ulysses Baker went to his regular lunch engagements at the American Club and he made sure to bow and politely acknowledge Mr and Mrs Lobchenko in a way that reminded them that the Bolsheviks had not completely destroyed good manners everywhere.

Mr Shu’s wife, known to everyone (except him) as simply “ayih”, swept the communal areas and kept the banister brass shining. The couple lived in a small suite of rooms provided for them behind the reception desk, which meant Mr Shu, who slept lightly, appeared to be constantly on duty.

The Gascoigne was a small apartment building by Shanghai standards, though it did have a lift. But the Carmichaels, Bakers, Dumonts and Lobchenkos never used it. They all apparently preferred the stairs. Only Mr Milton, who occupied the entire top floor, used the lift.

The penthouse was truly impressive, with a wraparound balcony affording an amazing view over the city. It had been the first apartment to sell, the asking price reportedly astronomical. But Milton had paid cash, delighting the developers.

Sex, violence, suicide: Italian love triangle scandal in 1920s China

He was by far the youngest of the Gascoigne’s residents, by at least three decades. Mid-30s, a rather unruly shock of blonde hair, probably British, though his accent had the twang of an Englishman who’s lived overseas for many years.

Milton kept to himself. He came and went mostly late at night, occasionally accompanied by exotic female visitors whose bare legs and arms rather scandalised poor Mrs Lobchenko.

Out of politeness Milton was always invited to the Carmichaels’ Christmas Eve party, but in the five years they had all lived in the Gascoigne he had never accepted. Though this year, much to everyone’s surprise, an acceptance note had been slipped under the door for the first time.

And so that Christmas Eve all the residents were preparing to attend the Carmichaels’ traditional festive soirée, starting at 6pm prompt.

Six years, since that business at the jewellers on Nanking RoadDetective Chief Inspector John Creighton, to his ex-police colleague Atma Singh

But we mustn’t forget Atma Singh, who was not technically a resident but was known to all as the man in charge of the basement boiler keeping the building nice and warm.

Singh was a Sikh from Patiala who had originally come to work for the Shanghai Municipal Police many years earlier. Since then he’d been a security guard and, when the Gascoigne was built in 1925, had been hired immediately before anyone had moved in.

He lived and worked alone in the basement boiler room, which was accessed by narrow steps at the rear of the lobby. Though basic, it was a most cosy room when, like this Christmas Eve, it was snowing outside.

Singh rarely appeared above the basement. Still, he knew all of the Gascoigne’s residents and, as the provider of their winter warmth, he was greatly appreciated by them. Every year he, too, was invited to the Carmichaels’ drinks party and always attended.

Christmas Eve rolled on with the residents coming and going with parcels and presents. Local stores sent boys with food deliveries, vintners’ crates arrived, Christmas cards were dropped off, festive telegrams received.

The Carmichaels wrapped themselves up in their great coats to visit the Bubbling Well Cemetery, where their son, David, was buried, and lay a wreath as was their annual custom.

The Lobchenkos paused on the way home from the Russian delicatessen on Rue Molière at the nearby cemetery where their daughter, Anastasia, had been laid to rest.

The Dumonts took a nostalgic stroll along the busy, lit-up Nanking Road to where they had once had their jewellers. Madame Dumont shed a tear for what had once been.

The Bakers sat at home, sipped sherry and remembered Christmases past. The Shus didn’t celebrate Christmas but they did enjoy the decorations and the general busy-ness of the Gascoigne at this time of year.

They also appreciated that the Carmichaels always invited them for a drink, something that didn’t happen to concierges at most Frenchtown apartment buildings.

Milton had returned in the early hours of the morning, alone and quite drunk. He had spent the day in bed with a hangover.

Detective Chief Inspector John Creighton liked Christmas – a few drinks, a good lunch, presents, his wife and children all around him. So this year, after finishing some paperwork and enjoying a traditional nip of whisky with the desk sergeant, he was heading home to his family and a roaring fire.

His last job was to stop in at Egal’s the vintners on Avenue Joffre for the Christmas wines.

Singh had spent the afternoon shovelling coal into the boiler, ensuring there was plenty of festive warmth. He decided to step outside for a smoke before washing up and changing for the Carmichaels’ party.

What would Shanghai look like almost empty? Artist who stripped cities bare

The night was drawing in, the streetlamps already lit. He noticed the snow settling heavily along Avenue Joffre. Snow had not been part of his Punjab youth and there was still, even after so many years in Shanghai, something special about it.

Singh fumbled with his matches trying to shield the light from the wind. Then he saw the big stubby flame of a Ronson lighter, looked up and saw his old boss, DCI Creighton.

“PC Atma Singh, as I live and breathe …”

“DCI Creighton … it’s been …?”

“Six years, since that business at the jewellers on Nanking Road?”

Singh looked downcast, “Now I’m the boiler man here at the Gascoigne.”

Creighton just nodded. They’d both joined the force around the same time. Great War veterans with no desire to return home. Over a decade had passed since then.

The two men shared a cigarette, then another, and reminisced before Singh said he’d better get back to his boiler. He wished DCI Creighton a merry Christmas.

Creighton wasn’t quite sure what to say. Did Sikhs celebrate Christmas? Singh saw his hesitation and said, “You know I always enjoyed the traditional nip of whisky with the desk sergeant on Christmas Eve.”

The art school that gave early 20th-century Shanghai its ‘look’

Creighton headed up Avenue Joffre to Egal’s Wines, Frenchtown’s best vintners. Fancy bumping into old Atma Singh, he thought, a good copper, a reliable man. But Sikhs didn’t get promoted to detective in the Shanghai Municipal Police, so he’d left to find more lucrative work.

Creighton remembered him as a man who believed in justice, that criminals should always pay. That Singh was never promoted above constable was a travesty, a career denied due to stupid prejudice.

Creighton remembered being at the station almost exactly six years earlier, not then senior enough to get out of Christmas Eve duty. The news of a robbery gone terribly wrong on Nanking Road came in. A double murder of two jewellery shop assistants. Singh had been the store’s guard, coshed unconscious by the robber.

Creighton had interviewed the dead couple’s parents. They said the two had been married only weeks before. He quizzed the one woman who had been a customer in the shop at the time, but she had been so scared, crouched under a jewellery cabinet, she could recall little.

Singh was the only person left alive who had seen the murderer up close. But he couldn’t identify the man, it had all been so fast – beyond European, maybe an English accent, a scarf over his face, a trilby hat pulled down tight.

Watch shop robber can’t do the time, asks judge for death sentence

Creighton had appealed for witnesses, canvassed the usual suspects, tapped his underworld informants. But all came up blank. It was a terrible tragedy. Two families destroyed on Christmas Eve, the shop’s owners distraught, the lady customer terrified.

Creighton’s inability to solve the case had long gnawed at him. Such unnecessary violence to steal a sack of diamond bracelets and gold rings.

Eventually the newspapers moved on to new crimes. The case stalled, then went cold, then was forgotten. Creighton knew that a man as principled as Singh would always feel awful for not preventing the double tragedy that December 24. He knew instinctively that it would weigh heavily on the man this Christmas Eve anniversary.

Creighton paid for his wine order and gave the delivery boy his address. Then, on a whim, he bought a bottle of decent whisky. Maybe Singh would appreciate a nip this Christmas Eve, like the old days? His roaring fire was waiting, but surely he had time for an old comrade.

It was chiming 6pm on the clock in the Gascoigne’s lobby when Creighton walked in, bottle under his arm. The place seemed deserted. A small decorated Christmas tree stood on the concierge’s desk.

Creighton called out down the back stairs for Singh. No response. He walked down the steps into the boiler room. There was the red heat of the well-tended fire, a pile of coal, a shovel, a small table and chair with a thermos and newspaper, a neatly made-up cot bed, but no Singh.

DCI Creighton, I was not expecting you to return to the Gascoigne tonightAtma Singh, ex-policeman

He left the whisky bottle on the table with his name card and scrawled a short note – “a nip or two for old times!” He went back up to the lobby ready to finally head home … and then he heard the shot.

The gunshot sounded loud, from the floor above. Creighton took the stairs two at a time up to the first-floor landing. There he saw two apartments, one on each end of a corridor. A Christmas wreath on the closed door of one, the other wide open.

Creighton smelled cordite, an all too familiar odour to a Shanghai policeman. He heard the sound of sobbing coming from inside the open door.

Creighton cursed himself for having checked his service revolver in at the station armoury before leaving, but he didn’t like the idea of a gun around the house at Christmas.

He moved cautiously to the apartment doorway. Looking in on a large living room, he saw the lifeless body of a blond man on the floor, a discarded revolver lying near the corpse, blood seeping from a bullet wound in his chest onto a white Tientsin rug. A man was crouched beside the body.

All around stood a group of men and women, couples hugging, the women in tears, a Chinese couple standing slightly back watching, and all of them in party hats, with drinks. The figure crouched by the corpse turned and looked up towards Creighton, who saw it was Singh.

“DCI Creighton,” he said, “I was not expecting you to return to the Gascoigne tonight.”

When humiliated second wife murdered her Hong Kong husband’s concubine

Everybody in the room stood stock-still and stared at Creighton. He walked forward, picked up the revolver, spun the cylinder removing the remaining bullets before putting both the empty gun and the bullets in his coat pocket. He looked at Singh, now kneeling beside the corpse.

“Who is this, Atma?”

“This is Mr Milton, DCI Creighton. He lives in the penthouse and this year he came to the Gascoigne’s annual Christmas Eve party for the first time. We have waited for him to come for five years. Every Christmas Eve we waited, but he never came before.”

“What on Earth do you mean?”

“He moved into the Gascoigne first, bought the penthouse. I knew him straight away, it all came back to me when I saw him in the lobby the day the Gascoigne opened … his blond hair, the accent, the look in his eyes. So I told the others.” He motioned to the guests around the room.

“And one by one they moved in, took the remaining apartments, became the building concierges. And then every Christmas Eve we gathered and invited Milton to join us. But he never did, not until today.”

When a madman murdered 5 people in their sleep in Hong Kong

Creighton look around the room. He realised that all the party guests appeared to know him. And then, slowly, he, too, recognised them.

That day, Christmas Eve, six years ago. He had rushed from the station to Nanking Road, to the jewellers, owned by a French couple called Dumont. There he had found Singh just regaining consciousness after being clubbed by a robber.

He had tried to question the only customer in the store at the time, an American woman, Fiona Baker, but she was too distraught to even speak. And then on the shop floor, among the smashed glass of the shattered and emptied cabinets were the two young shop assistants, shot dead – the newly married David and Anastasia Carmichael, née Lobchenko. He’d had to notify Mr and Mrs Lobchenko.

Alexander Lobchenko had tried to retain his composure, though tears had streamed down his face. His wife, Yulia, had collapsed into the arms of the dead girl’s Chinese ayih, a Mrs Shu, who had cared lovingly for the child since her birth.

Creighton saw them all – Singh, the Dumonts, the Bakers, the Shus, the Lobchenkos and the Carmichaels. Older, aged by grief from that terrible Christmas Eve. And, on the mantelpiece, he saw the photograph of the dead couple, David and Anastasia, happy on their wedding day, now framed in black ribbon.

They had all waited five long years to confront the man who had fired the shots that destroyed their lives. They gathered every Christmas Eve without fail, but also without luck. Then Milton, never suspecting who his neighbours were, had accepted their invitation, unknowingly stepping into the Christmas party in the Carmichaels’ living room to meet his fate.

Creighton surveyed the party guests. Who should he arrest? All of them? Three grieving old couples and an ayih, a woman still too terrified by that Christmas Eve that she was imprisoned in the building, a lonely boiler man who had tortured himself as responsible all these years?

He couldn’t be sure who had pulled the trigger. But where to apportion blame anyway in such a case?

When a ‘spurned lover’ bombed a Hong Kong hotel to harm his love rival

Creighton could see no way to resolve the situation without causing more pain for all involved. How could Shanghai’s courts ever sort this out without yet more misery? Without grieving old men and women going to prison and Singh getting a date with the hangman?

Creighton could see no way to resolve the situation without causing more hurt for all involved. So he decided to just turn and leave, head back down to the lobby, out onto the snowy Avenue Joffre, and home to his Christmas fire; to leave the residents of the Gascoigne to their Christmas Eve tasks this year, which appeared to consist of rolling the dead body of Milton up in the Carmichaels’ Tientsin rug and taking it down to Singh’s roaring boiler to heat the building for Christmas Day.

Creighton knew he would probably never see a missing-person report on Milton. Who would miss him? And that he would probably see a penthouse apartment For Sale sign outside the Gascoigne when he wandered past, along Avenue Joffre, in Shanghai’s Frenchtown, back to work, Christmas over, in the New Year snow of 1931.