- Now showing in Hong Kong, New York-based Otero opens up on working in a church during the pandemic and why his grandmother is so important to his work

In early 2020, Angel Otero, an artist from Puerto Rico with a studio in Brooklyn, New York, was looking for a space outside the city. He wasn’t escaping Covid, which had yet to shut down the globe, but a bolt-hole from the art world.

He was 39, represented by the Lehmann Maupin gallery, not stratospherically successful yet definitely getting attention, but he wasn’t sure how he felt about himself.

“Honestly, I think previous to the pandemic, there was this sort of Angel that questions everything, wasn’t sure, was very timid to take certain decisions,” he says, on a chilly, wet New York morning in January 2023. Otero has such an engaging cheerfulness, and his work is so vibrant, it’s difficult to picture this lack of buoyancy.

“The lady [property] broker was, like, ‘Hey, I run out of options for you, you don’t like nothing. I’m going to show you the last thing and it’s a church.’ When she said that word, my toes really crumbled because I grew up Catholic, right?”

In fact, it wasn’t a Catholic church, it was (decommissioned) Methodist, built in 1867 in the Hudson Valley.

“Maybe I’m not as deeply religious as maybe I was as a kid, when my grandma would take me to church, but that environment – the echo, the lighting, the sculpture, the high ceiling, just everything – was so, so celestial and magical.”

Magic – especially magic realism as exemplified by Gabriel García Márquez’s 1967 family saga One Hundred Years of Solitude – feeds Otero’s imagination. He likes to quote the opening line, in which Colonel Aureliano Buendia, facing a firing squad, recalls the distant afternoon when his father takes him to discover ice.

Pope to visit Canada in July, expected to apologise for residential schools

In March 2020, New York’s shutdown began. Otero closed his Brooklyn studio, packed some of its contents into a U-Haul truck and headed for his church, and spent eight months there.

It hadn’t been renovated but he liked living amid the diminished outline of its past, although he agrees he was freaked out by the bats.

He’d taken some of his old work with him. The canvases prodded him to remember his own history: he missed his student days at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and his early years in New York.

He’d loved doing figurative work based on his childhood in Puerto Rico. He’d had an edge then, an ambition fuelled by a sense of his individualism. “And that had completely blurred over time.”

Since 2010 he’s been best known for his abstract “skin” paintings. This is a process in which he paints an image on plexiglas, waits for it to dry, adds another image, waits, adds another … Eventually the hidden layers take on an almost three-dimensional quality. Then he peels the work off, like a scab, and places it on canvas.

But the repetition had left him feeling a little raw. “I was influenced by what was going on in the art world, the market, the relationships. I was tired and overwhelmed. So the fact that I was alone in a space, that I could make art alone, without deadlines – it was super thrilling.”

When he eventually returned to his studio, his church retreat had, as he puts it, “really created a humongous change on me”. Post-pandemic, he saw a way to combine both aspects of himself – the content of the figurative work with the process of the abstracts – and his confidence soared.

In early 2021, he had a show at Lehmann Maupin called “The Fortune of Having Been There”, in which he added clearly visible scenes from his Puerto Rican past to the abstracts.

That same year, like magic, his auction record was broken three times; in June 2021, a 2013 skin painting, Acis and Galatea, with a presale estimate of US$25,000 to US$35,000, sold for US$277,200.

At the beginning of 2022, he was taken on by Hauser & Wirth and, in November that yea, at its Chelsea gallery in New York, “Swimming Where Time Was” was his first show featuring figurative and abstract works hung side by side.

He wanted to convey how time takes the present and compresses all our vivid moments into the past, yet even though so much is obliterated, certain objects can still trigger associations. Despite regaining his mojo, he was worried.

“I didn’t want it to feel, like, commercially – ‘Hey, I can do a little bit of everything!’ I wanted it to be connected. And it really came out fantastic, very honest.”

His new Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong show, “The Sea Remembers”, is an extension of those themes. He uses a quirky assembly of items – a rotary telephone, board games, false teeth – to dive into his relationship with fading recall and identity. And appropriately for Hong Kong, Otero also tries to grasp at a lost time on an island with a colonial past. (Puerto Rico is an “unincorporated territory” of the United States but is neither a state nor a country.)

His collages are hidden layers of memory – a palimpsest, as art critics like to say, although he puts it more simply: “It’s how I weave this persona, which, at the end, is just me.”

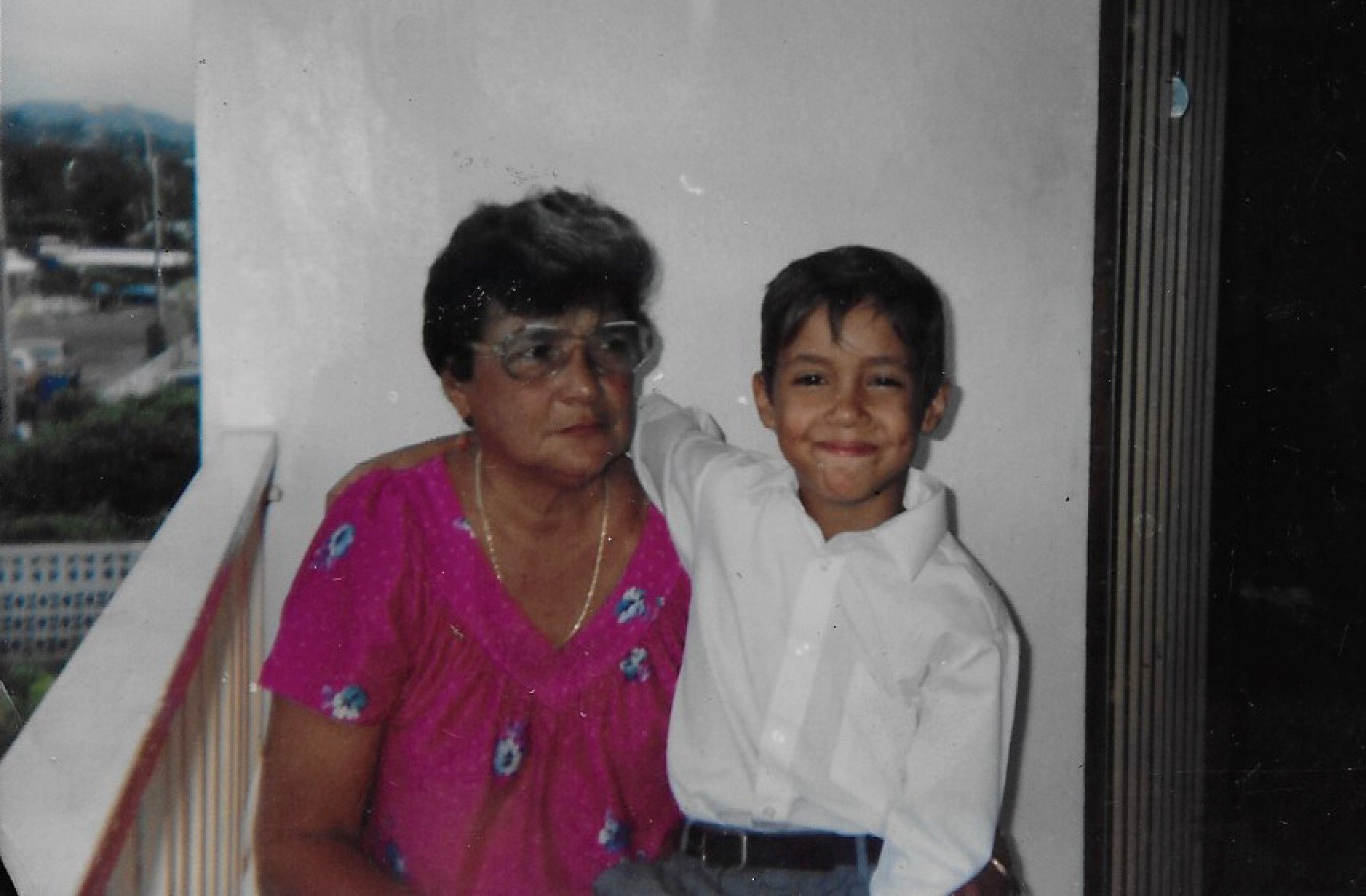

Otero has his own skin painting. His right arm is embellished with a tattoo of his maternal grandmother, surrounded by fans and flowers. Tattooed on his forefinger is Esperanza, the name of his paternal great-grandmother (and the middle name of his daughter, Stella, aged 10, with whom he does a dad-daughter private gallery dance before each show).

“I’m a grandma boy,” he says.

When he was young, his parents divorced and it was his maternal grandmother who brought him up. “She was my mom, my caretaker, my best friend, my … what’s it called … mentor.” She never slept in a bed, he says, always on a sofa.

“In my figurative work, you’ll see a lot of oddness – you’ll see weird chairs inside a fridge, on top of a couch, chairs inside of a tub. I think certain objects in a composition are really a sort of way of placing the human figure.”

At six, he began drawing cartoons. He would watch the American artist Bob Ross, whose 1980s television series The Joy of Painting ran for 403 episodes. By the time he was applying to the Universidad de Puerto Rico, his teacher urged him to choose art.

At 21, he dropped out when his father, an insurance agent, insisted his son go into the same business. One of his former professors prodded the admissions department from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago to write an encouraging letter, and Otero was offered half a scholarship (and, later, a full one). At 23, he left Puerto Rico for the US mainland.

On his first day in class, everyone was asked to name a favourite contemporary artist. Otero chose Jackson Pollock. After his fellow students stopped laughing, his professor put an arm around him and said, “How does it feel to live in the 1950s?”

“You know, I entered this environment of the art world in a very naive way,” he says in his Brooklyn studio. “I was like, ‘Oh, I have to go to grad school now? Yeah, if you go to grad school, you’ll get a gallery. Oh, OK.’

“So I apply to grad school. Then people say, ‘Oh, these are the big galleries and important artists and collectors.’ I didn’t know there were collectors – I thought there’s people who buy art!”

By now, he was in New York and painting what he remembered of his life in Puerto Rico.

“My work was very direct, very personal and transparent and I started quickly noting that people were … not mocking but a little thrown off by the way I was romanticising all my old memories of my grandmother.”

He falters for a moment, not wishing to sound disobliging. (As he says later, “I’m a people person and I know I took that from my family – they’re extremely respectful of others, they want everyone to be happy.”)

Didn’t someone make vomiting gestures about his grandmother-as-art-topic? “He did. He’s a nice guy, someone I know. He was, like, ‘I really love your work, I do but I don’t give a f*** about your grandma – just let the work be.’ That hit me. That hit me very hard.”

At the same time, Otero wanted to explore his skin paintings’ potential; these had begun small when, in an effort to save money, he’d scraped off, then reused, the dried oil paint on his palette.

“I wanted them to be big, on a monumental level,” he says. “It took me a while to figure out the process, materials and all that. But when I did, wow. And I quickly stopped that other body of work. Because, yeah, it became too … I was being too open.”

In the studio, he gives a quick demonstration of his skin technique. “There is a therapeutic aspect, yes. Now I have people help me do it [he has three assistants] but, in the beginning, it was very strange, very physical.

“When you’re applying oil paint, it’s still alive. It sweats, it has a smell, the quality of it is so connected to the body. That’s why I started calling them skins.”

A poster of Bob Ross – not someone you’ll see in most creative lairs but Otero seems innocent of pretension – has the words “No mistakes, only happy accidents”.

The pandemic, when he couldn’t visit his family in Puerto Rico, the global sense of mortality, those months in the church – all primed him, finally, to knit skin and memory together in an unashamed way.

“Art for me is not a way of necessarily exposing something or telling something. It’s also about a personal search, right?” He adds that he wants to connect what was confusing about this childhood to the man he is today.

Asked about that confusion, he considers for a moment, then says, “I had a tendency to compare myself in my life towards other people’s lives and environments, there was always a curiosity.”

A Chinese artist made Tintin less racist, became one of Hergé’s best friends

And envy? “No.” Or yearning? “What’s that word?” When you really want something … a place, a life. An identity? “Yeah. Growing up in Puerto Rico, identity can be very complex. My family was extremely humble, loving. But, in a certain sense – being human, obviously – they desired better things than they had.

“If my dad saw someone with a nice car, he’d be, ‘Wow, that person has a lot of money, that’s a real successful person.’”

They’re proud of their real successful son, then. Otero laughs. “Yes, 100 per cent. It’s funny that we’re talking like this – these are questions that now, as a man in his 40s, I ask. I go back to visit my dad, who’s very ill, and he says to other people, ‘You should google my son, he has this car, check it out.’

“His friends are like, ‘How much you sell your paintings for?’ And I’m, like, ‘Dad, don’t speak!’ I got to calm him down. So that’s my environment, and all the decisions I make about what works in the paintings are based on growing up in that.”

Sometimes you’ve got to leave home, take a break. And then you miss home, you have to return and you see it a little differentAngel Otero

Four months later, on May 31, Otero is standing in Hauser & Wirth’s Hong Kong gallery. It’s the hottest day of the year so far and his tattoos are on display, including a glimpse of the one curling across the top of his chest that states, in Spanish, If you don’t know how to fly, you’re wasting my time – a terse example of magical realism by Argentine poet Oliverio Girondo.

Otero wouldn’t be so abrupt, and despite jet lag he still makes every effort to be courteous. The only moment his smile sags is when he’s presented with a glass of warm water. (Like Colonel Aureliano Buendia, he longs for ice.)

Later, when the show opens, Elaine Kwok, Hauser & Wirth’s managing partner in Asia, will remark that he’s the first artist, on such an occasion, ever to send flowers to the gallery.

Those months ago in New York, when he was just beginning his preparations, he’d stated that he’d wanted “to build some sort of bridge” with Hong Kong. A first-time viewer might assume that, for example, the fans are a Hong Kong tribute but, as his right-arm tattoo proves, fans have always been associated with his grandmother.

Hong Kong is probably one of the few places in the world where the template of Angelic themes – maritime history, family, identity, memory – fits over his own.

“Sometimes it’s a little tricky,” he says, looking at his figurative and abstract works. “I have these moments when I need to distance myself from the directness of the figurative works. Then I do the abstracts. Each informs the other. After a while I’m ready to go back.”

He adds: “Sometimes you’ve got to leave home, take a break. And then you miss home, you have to return and you see it a little different. It sounds metaphorical …”

But he’s not speaking in metaphors. At the opening, he reveals he’s planning to leave New York and live once more in Puerto Rico. The shift will be “gradual”. Some yearning is at work that he can’t, yet, enunciate. Maybe he’ll keep the studio (and the church) in New York, maybe he’ll go back and forth.

But doesn’t an artist have to leave in order to create? “I’m curious to know how it will feel back at home,” he replies. “I want to see the culture of my home and how that evolves.”

Angel Otero’s “The Sea Remembers” continues at Hauser & Wirth, 15/F-16/F, H Queen’s, 80 Queen’s Road Central, until July 29.