- The hard-partying septuagenarian opens up on his long photo-art career that has seen him travel the world and rub shoulders with film and TV luminaries

The day before this interview, Basil Pao Ho-yun had made a night of it at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Hong Kong.

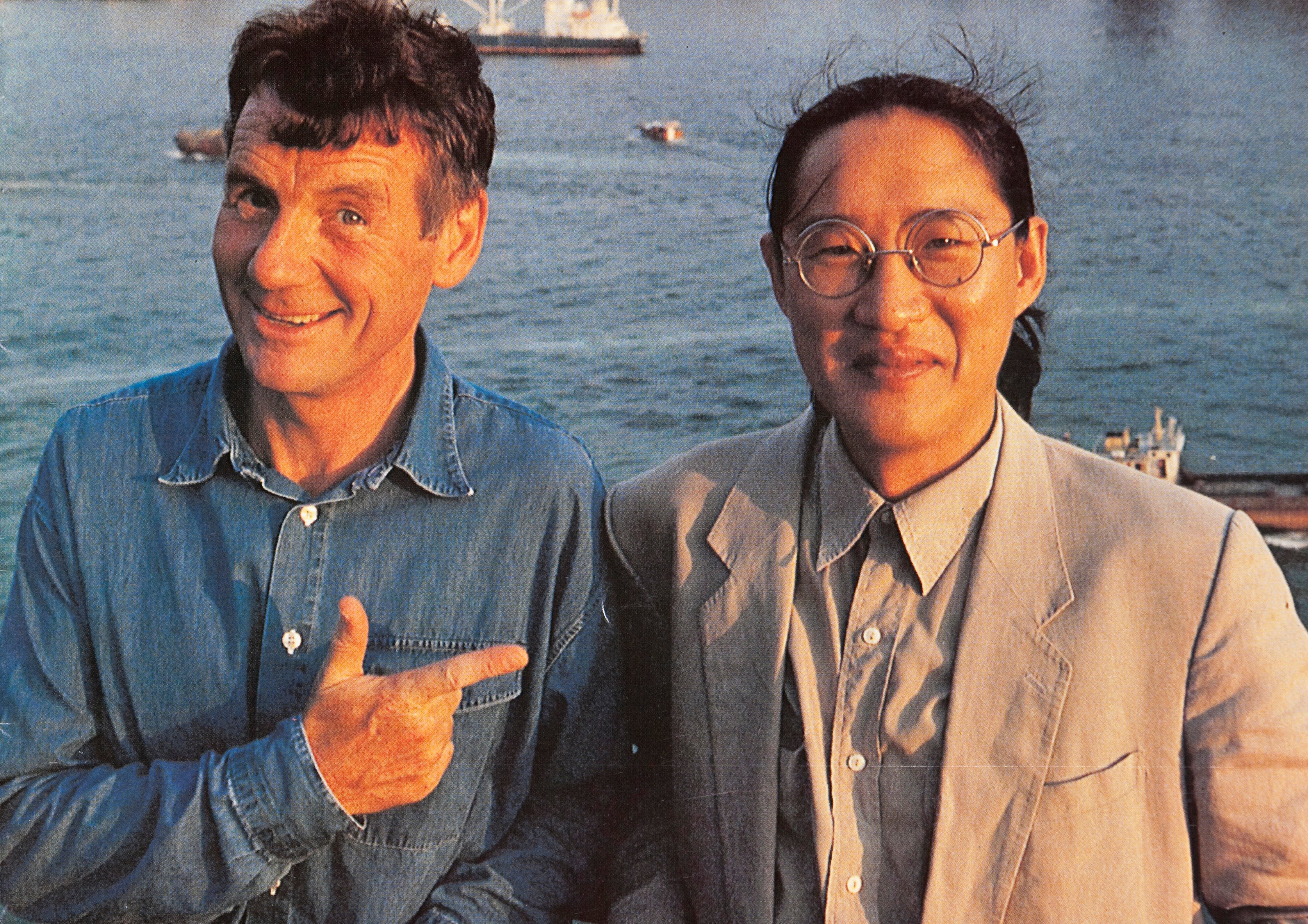

As a result, when we meet at the crowded Cheung Chau ferry pier – the photographer instantly identifiable by his trademark panama hat, a signifier Michael Palin also found useful when they travelled the globe for his BBC television series – Pao is feeling, as he puts it, “delicate”.

He suggests a nearby outdoor restaurant, where he’s a regular, to see how things go.

Over four enjoyable hours, several glasses of white wine are consumed, although your correspondent sticks to tea. (“I know – incredible that somebody I’m with could not be a drinker,” he says to the waitress.)

Before the first sip, he remarks, “I turn into a beast when I have too much.” Had he been beastly the previous night? “Oh, very abusive, very nasty.”

Indelicate swear words certainly multiply as he perks up, but there are no signs of brutishness and when I ask around later, people make approving comments about his charm as well as his talent so, presumably, that’s one of his jokes.

After all, much of his professional life has been spent in the company of Monty Python’s Flying Circus alumni: the British streak of self-mockery and leg-pulling runs deep.

We’re here to discuss three books he’s bringing out with Hong Kong University Press (HKUP) this summer.

Ex-spies, drag queens: photos from fringes of Taiwan society in Hong Kong show

One is The Last Emperor Revisited, a collection of photographs from his time on the set of the 1987 Bernardo Bertolucci film about the life of Puyi.

One is OM² – Ordinary Moments+, an anthology of 140 photographs, boiled down from those taken during the many thousands of miles he’s travelled in almost four decades.

The third is Carnival of Dreams, a selection of Pao photomontages, beginning with the 1970s album covers he designed in Los Angeles and continuing, through a wide arc of time and place, up to recent Cheung Chau creations. The book was launched this month, the first of the three to be published.

“I have worries about it,” he frets. “I don’t know if there’s an appetite for this sort of work. It’s a very iffy thing.”

By “this sort of work”, he means surreal images in the style of René Magritte, and collages à la Terry Gilliam, a Python alum who achieved later fame as a film director of dark fantasies such as Brazil (1985), 12 Monkeys (1995), The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009) – but began as an animator.

The opening credits of Monty Python’s Flying Circus – featuring Victorian cut-outs, unhinged heads, giant feet, rude noises – sprang from Gilliam’s imagination and were then, to use a favourite catchphrase, something completely different, and his fever-dream creativity was a crucial contributor to Python’s success.

After much prodding, Gilliam has provided a foreword to Carnival of Dreams, and Pao places his iPad on the table so I can flick through the proof copy.

“He needed a trigger, he didn’t want to write a fluff piece,” says Pao. “Mike [i.e. Michael Palin] is good at writing them for me because he’s written so many and each one is more fluffy than the last.”

True to form, Palin has supplied the foreword for OM² – Ordinary Moments+, describing it as “the crème de la crème of someone who always insists on the highest standards” and “a perfectionist’s choice of a perfectionist’s work”. By way of contrast, Pao suggested that Gilliam write about how he – Pao – has been ripping him off all these years.

Fired up, Gilliam went home and concocted a whimsical scenario: “Behind Basil’s wry and slightly Oriental smile […] little did I know I’d befriended the Fu Manchu of the art world […] I shouted ‘Stop thief’ but he merely smiled inscrutably, leapt into a passing palanquin and was gone!”

“We’re not PC people,” Pao smiles, scrutably, when I wonder aloud in which century this was composed.

How Samsung’s and other AIs create realistic-looking photos that fool us

“I’m sorry, we’ll never be woke, we’re too old to be woke.” And, as a murmured afterthought, “He’s been cancelled, actually.” (In 2021, Gilliam’s production of Into the Woods at London’s Old Vic theatre was pulled, apparently because of staff concerns about Gilliam’s forthright opinions on trans rights and diversity.)

Presumably no one’s going to cancel HKUP because of a Gilliam parody, though it’s hard not to wince at Pao’s 1977 album cover for Nektar, an English rock band, that features Brooke Shields, aged 12, in a microscopic dress, superimposed on a waterfall.

“She’s a sweet little girl,” he says. Exactly. “It was my idea but a friend photographed her. Different times.”

Ah, the ’70s. In Pao’s telling, it sounds like a simultaneous heaven and hell. When the decade began, he was a Hong Kong lad enjoying art classes at Kingswood School in Bath, England; when it ended, he was a burnt-out art director and recovering cocaine addict, back in Hong Kong.

He’d gone to boarding school because, he says, he was teetering on the brink of expulsion from Hong Kong’s St Paul’s College and his father, who was then teaching juvenile delinquents “and some of the most notorious murderers” in Stanley Prison, was worried his son was heading down the same path.

I’d read a reference to teenage gambling and Pao, who likes to be entertaining but occasionally thinks better of it, begins a story about being treasurer in charge of buying plastic lunch tokens that, somehow, segues into being so tall he had to sit at the back of the non-air-conditioned classroom where the windows were open and he couldn’t hear the lessons “and obviously academic work suffers”.

They dubbed me – with a lisp no less. That completely destroyed my film careerBasil Pao on his part in The Last Emperor

In England, however, his art master gave him the run of the art room and allowed him to watch Monty Python, classified as adult viewing by the BBC, to be shown only after the 9pm watershed, when the rest of the school had trudged up to their dormitories.

By the time he was 18, in 1971, Pao was at ArtCenter College of Design in Los Angeles studying graphic design.

When he arrived, he was an innocent, but – “I’m still innocent! What are you talking about?” After I point out that even fluffy Mike refers to Pao having done “all sorts of naughty things” he mounts a half-hearted defence (“When did he say that?”) before he observes, again, “Yeah. It was the time.”

Success came when he was astonishingly young. In 1974, he did his first album cover for Atlantic Records. It’s in the book; it was called Crosswinds, it featured the work of drummer Billy Cobham, and it was Cobham who snapped the swirling vast-sky photo that flows over front and back.

In those days, Pao didn’t take photographs. “I don’t think I had a camera back then because I was An Art Director – you know, the help does that kind of [stuff]. I’d just say I want this, go do it.”

He moved to New York, where he became Polydor’s art director. Then he was headhunted, by Warner Bros Records’ Los Angeles office, and returned from lunch one day to a message that Eric Idle, the musical Python, had rung; he wanted an album package for his band The Rutles, whose sole ambition was to parody The Beatles.

Pao, coolly used to famous names, was thrilled. A meeting was arranged, and, much like today, the night before was a late one. “I think I was celebrating the fact that I was meeting Eric Idle the next day.”

In those days, Pao’s hair reached halfway down his back, and for reasons best known to himself, he put on a Lone Ranger mask that happened to be in the office. Luckily, Idle, confronted with such a vision, began laughing. “And I banged out the package – a 16-page booklet of stills and stuff – in a week.”

This was Pao’s passport to Pythonland. In his telling, it sounds exactly like a private boys’ school, with its in-jokes and fallings-out.

I’d hoped that he and John Cleese would have a running gag about Pao’s English name, given that Cleese is also famous, at least in Britain, for Fawlty Towers, a 1970s comedy series in which he plays an extravagantly rude hotel manager called Basil. But no.

“We don’t get along with John,” says Pao, referring to Palin and the two Terrys – Gilliam and Jones. “Sorry to disappoint, he doesn’t know I exist.”

He and Idle would eventually fall out over some Python-related editorial decisions, and back then “everything was very rushed and I was very high. I kind of lose control when I’m taken beyond some point with booze and drugs”.

In LA, that point was being reached ever more quickly. He’s keen to describe one of the most bizarre moments of his life, at a party when Life of Brian (1979) was about to come out and he meets Keith Richards, who’s sitting on the floor, watching the film, and they shake hands but nothing is there.

“My God, that was weird.” I wait a bit, but that’s it. That’s the story. How high was Pao? “Definitely not as high as he was.”

In 1980, Pao returned to Hong Kong, stayed with his parents in Pok Fu Lam, then moved to Cheung Chau to write the Great Novel, where he read many other novels, drank beer while watching the ferries and wrote an occasional observation in a notebook.

He began to take photographs for Cathay Pacific’s Discovery magazine and for the Far Eastern Economic Review. Now, he was the help, at the beck and call of other art directors. When he became desperate for money, he did album covers for Cantopop artists. (Some of these are in the collection of M+, Hong Kong’s museum of visual culture.)

Meanwhile, his father, Pao Hon-lam, had swapped amateur dramatics at Stanley Prison for TVB, and become a well-known actor.

In 1985, he had a role in Year of the Dragon, directed by Michael Cimino and starring Mickey Rourke. The supervising production coordinator was a young American-Japanese woman called Pat Fuji, who looked after the Pao parents in North Carolina, where a mock-up of New York’s Chinatown had been built.

When filming wrapped in Thailand, she passed through Hong Kong, and they invited her to dinner.

Pao Jnr was summoned, reluctantly, from his island lair. “And my father told Pat, ‘Oh, Basil will look after you while you’re here.’ They set me up, it was like an arranged marriage! We were engaged within a week.”

He proposed to Pat at the Cheung Chau Windsurfing Centre, and Carnival of Dreams includes a photomontage (in a style pinched from David Hockney, he says) of the building. His fiancée was presented with a plastic ring scrounged “from a packet” somewhere.

At the engagement party, photos were taken. Pat showed them to her casting-director friend, the aptly named Joanna Merlin, who waved her wand. Soon, Pao, nursing hopes of playing Puyi, was meeting Bertolucci, who decided he should be Puyi’s father, Prince Chun.

As it happens, I re-watched The Last Emperor recently and feel compelled to tell Pao that the toddler who played Puyi is the true thief, adorably stealing every one of their scenes.

“We hated that little [so-and-so]! He would not put his costume on – it was the height of summer in Beijing, all of these people were waiting in that heat. The amount of trouble [he] caused was unbelievable.”

Prince Chun has a single line, addressed to his fidgety son (“It will soon be over” – a knowing wink at history), which Pao claims to have diligently rehearsed “for weeks” with Cicely Berry, the famous British voice coach who was on the set.

“And they dubbed me – with a lisp no less. That completely destroyed my film career.” Channelling his inner Marlon Brando, he cries out to the Cheung Chau waterfront, “I could have been a contender!”

But at least he got to be a third assistant director on the film, a title he shared with various offspring from wealthy Italian families Bertolucci knew, who were there for fun; they were collectively referred to as Bernardo’s eunuchs.

[My website is a] disaster because I should be out there doing little clips, cooking spaghetti bolognese for the camera and talking to famous friends and [stuff] like that but that’s not meBasil Pao

The Italian photographer Angelo Novi was responsible for official stills on set while Pao, who had wisely taken Mandarin classes beforehand, dealt with the extras, and producer Jeremy Thomas asked him to take pictures behind the scenes.

“Before that, photography was just an excuse to get to Thailand for an in-flight magazine,” says Pao. “After Last Emperor it got serious. I suddenly saw the juxtapositions of cultures, the new and the old – the cameras, the lights, the costumes and those human moments between the people.”

A year after the film was released, Pao’s daughter, Sonia, was born, on September 25, 1988. At almost the same hour, Palin set out from London’s Reform Club for his BBC recreation of the 1872 Jules Verne novel Around the World in 80 Days. En route, he popped in to see Pao, who then joined him for the China section. This was another life shift.

In 1991, they did Pole to Pole although Pao did not, in fact, make it to either pole; there was room for the television-camera crew on board the light aircraft but not him.

“I was considered an appendage,” he shrugs. “I couldn’t shoot until they let me. That’s why I turned the camera the other way and those turned out to be the best shots. I don’t say, ‘Oh, that’s the action.’ I see what’s around the action.”

In the end, he and Palin did 11 globe-trotting, bestselling books. For Full Circle (1997), he spent almost a year on the road, setting out in August 1995. To console Sonia, who was almost seven, he took along a five-foot – 1.5 metre – inflatable version of Munch’s The Scream, promising to photograph it with children he met along the way.

In the foreword to his 2013 book The Universal Scream, he describes it as “her favourite toy” although it turns out she actually wanted him to take her panda, but it wouldn’t fit in his bag.

Despite some wonderfully photogenic encounters, I can’t help wondering how many children ran for the hills seeing this thing. He doesn’t remember exactly (perhaps more kids fled in religion-based countries, he thinks) “but it’s quite a cute little thing”.

It’s a symbol of 20th century angst, I protest, laughing; and Pao taps his iPad Carnival of Dreams and says, “This is 21st century angst. I’ve got a lot of [stuff] to get rid of.”

He’s serious, and smoking steadily now. “What’s weird about this book is it’s the first time I’ve had a reason to look back,” he says.

He has a house in the US state of Virginia and its basement is crammed with slides he hasn’t digitised or even glanced at for years. Pat, who teaches yoga, and Sonia, who does something inexplicable with websites, live there.

‘Happiness and revelry’: photographer recalls 2 decades of Hong Kong Sevens crowds

Earlier he had said, sounding a heartfelt note amid the jokes, “Pat was really the saviour. She still is.” But she’d rather not live in Hong Kong.

“Before, when the Palin thing was going full steam, it was a good spot to jump off from,” he says of Virginia. “Now all that has come to a grinding halt. I’d go travelling with Mike in a second, but it’s not going to happen because the budget is no longer there.”

He went back to the United States once during Covid-19, and did three weeks’ quarantine on his return to Hong Kong. “I think I changed after that. I lost the will to live. When I came out, you still had to wear a mask, you had to do this, you had to do that.” Different times.

In his photomontages, Pao creates new pictures by playing with his old ones: superimposing one stunning image – a river, a runway, a mountain – on another, slicing and reordering his world view from Cheung Chau.

Asked when he last took a photograph, he hesitates. “The Covid thing is definitely a killer. All the assignments stopped. I like catching people on the streets but they’re in masks. The only time I take pictures now is if there’s a really spectacular sunrise or incredible storm.”

On March 11, the day he turned 70, he happened to be giving a talk – “50 Years of Life-affirming Photography” – with the writer Pico Iyer at the Hong Kong International Literary Festival.

Iyer, whom he met in Nepal when Bertolucci was making his 1993 film Little Buddha, has also contributed a foreword to Carnival of Dreams. “I never know where to place Basil,” he muses. “Is he a Taoist Fellini? Or just a state-of-the-art contemplative?”

Early on, when I ask Pao for the answer, he replies, “How would I know?” Fair enough. He’s not one for selfies.

Photographer flips the script on Victorian portraits of ‘exotic’ Chinese

He agrees his website (which, when I checked before we met, seemed to have been abandoned circa 2012) is a “disaster because I should be out there doing little clips, cooking spaghetti bolognese for the camera and talking to famous friends and [stuff] like that but that’s not me”.

Towards the end of our afternoon, however, when I ask what happens next, he says, “Oh God. Make more books? That’s what I’m good at. It’s my graphic design training. I am about a piece of graph paper, a pencil and a ruler. And a calculator.

“To start and put down the first line and go from that to a finished book – that’s me. That’s what I do best.”