- The showman who brought Isaac Stern, Cliff Richard and Soviet artists to the city is remembered in a documentary that’s as much about the pair who made it

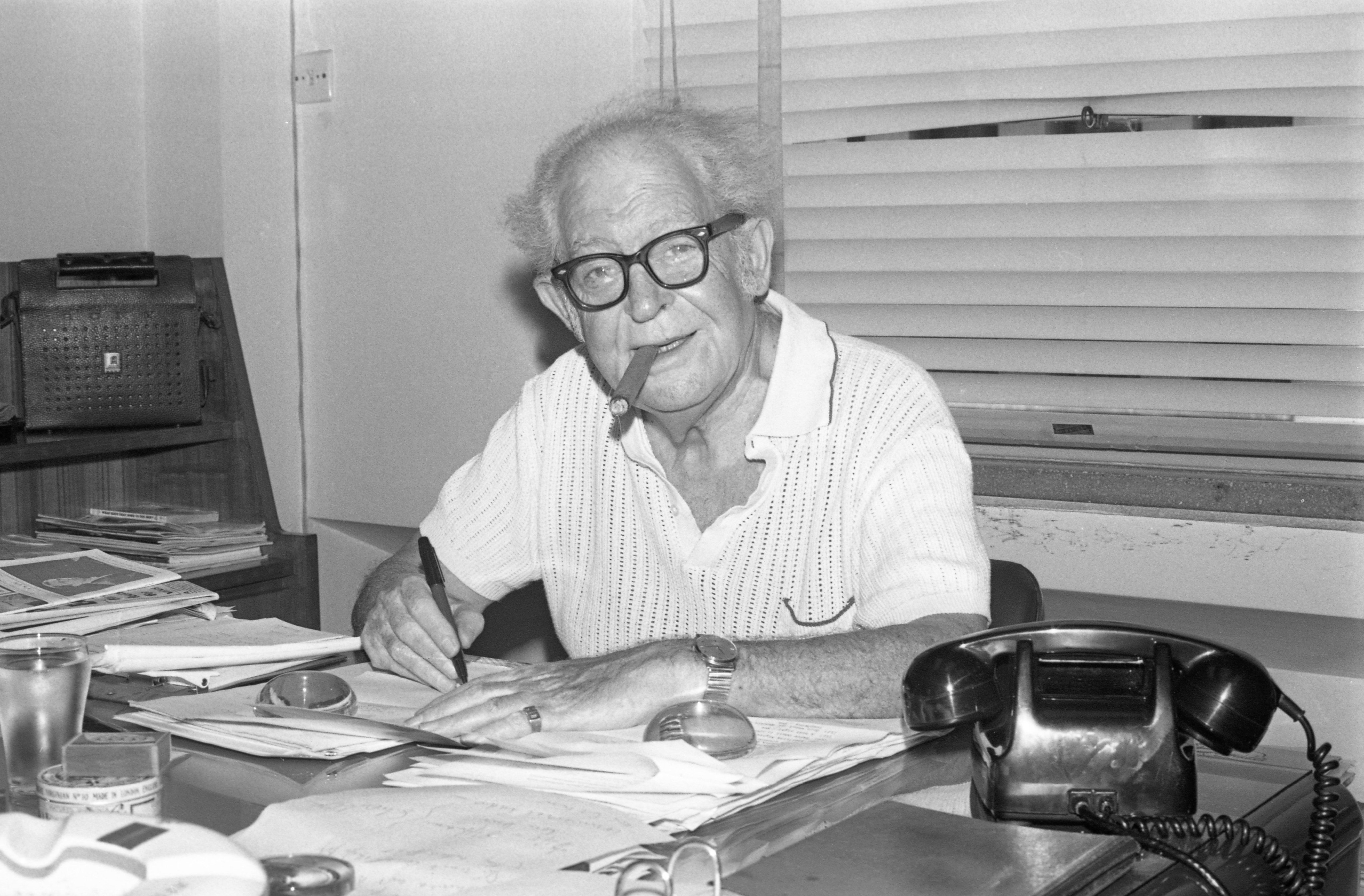

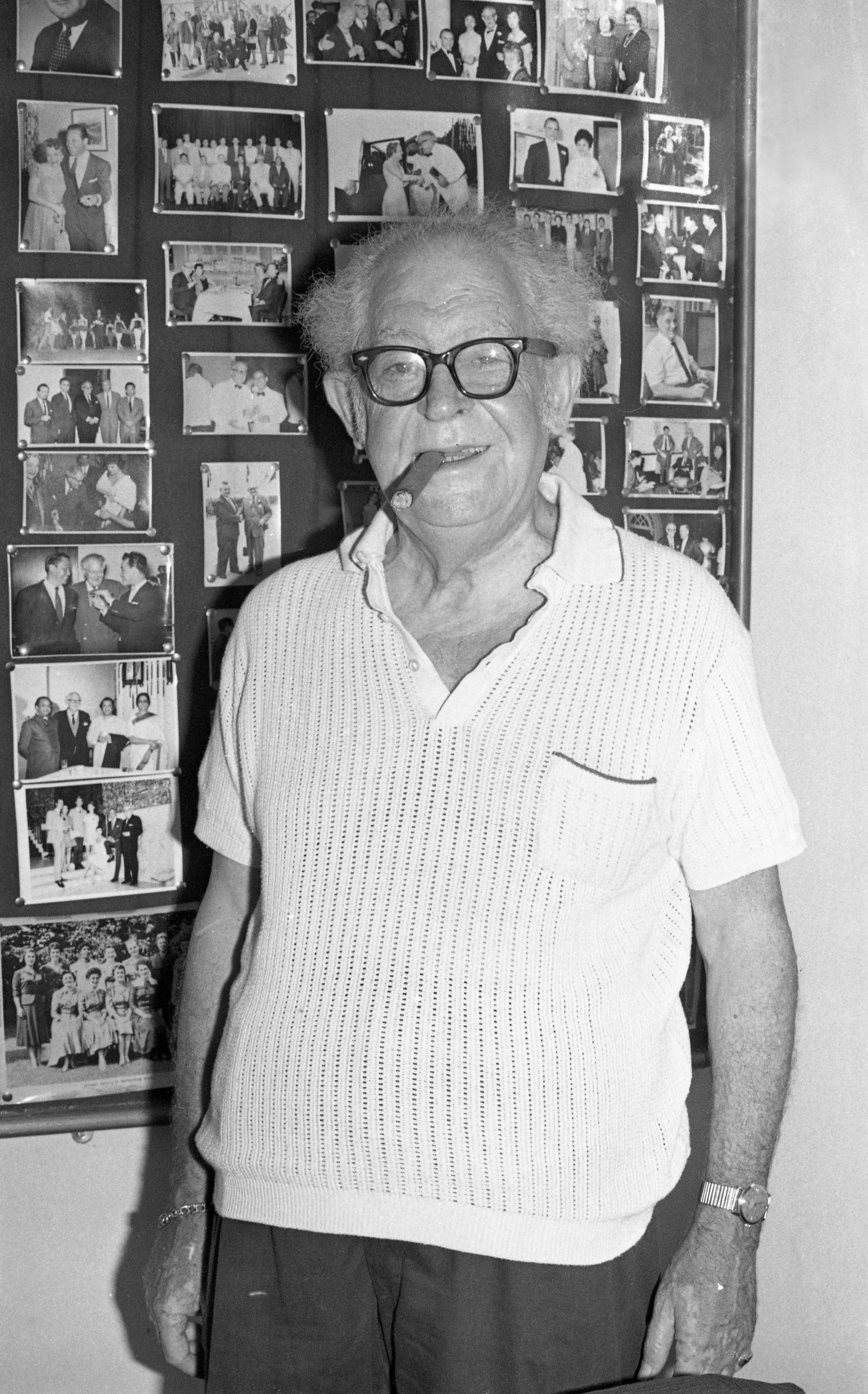

This is the story of one passion project that gave birth to another. It begins with an ardent, cigar-chewing individual called Harry Odell, usually described as Hong Kong’s first impresario.

In the late 1940s he set up a film distribution company and, for a while, owned the huge Empire Theatre in the city’s North Point neighbourhood, built in 1952.

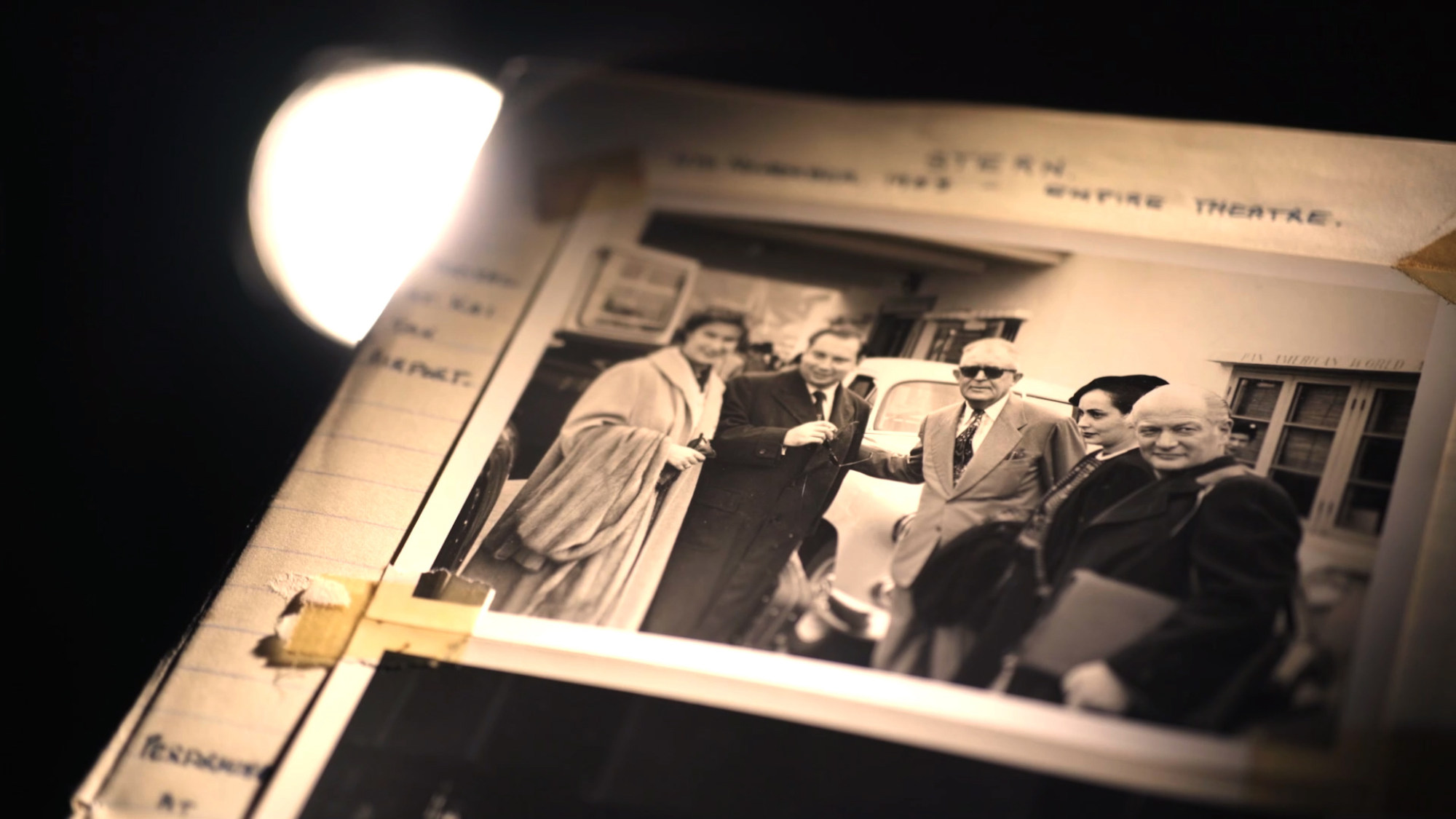

Odell’s dream was to bring world-class performing artists to the city. The Polish violinist Isaac Stern played at the Empire in 1953, as did the French cellist Pierre Fournier.

But by the time the Chinese Folk Artists Group from Guangzhou appeared in 1956 – the first Hong Kong visit by a troupe from mainland China since the Communist revolution in 1949 – the Empire was losing its lustre. (“Decrepit”, thought the South China Morning Post’s critic.)

The following year, the Empire closed, and when it reopened in 1959, it was renamed the State Theatre and had become a cinema.

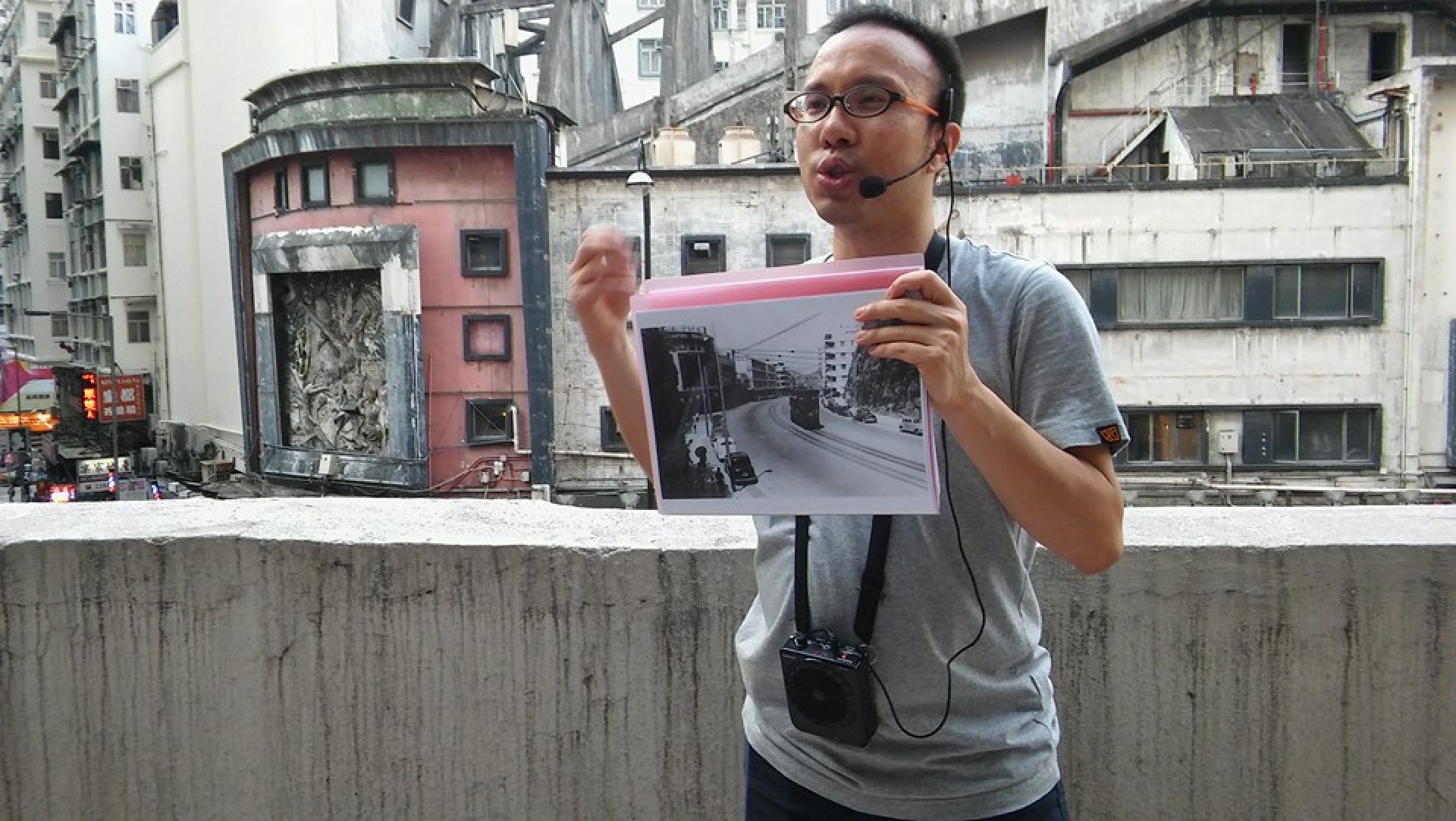

Half a century later, in 2013, a group of friends with an interest in local history started a company called Walk in Hong Kong. One of the co-founders was a man called Haider Kikabhoy, then a freelance editor. The first tour was round North Point and one of its stops was at the shuttered State: it had closed in 1997 and became a snooker hall.

Every evening, Kikabhoy roamed the internet to find out more. His friends grew used to midnight notifications as the latest Odell snippet pinged into their phones.

One of these recipients was Dora Choi Toi-ling, another co-founder of Walk in Hong Kong and, at the time, a documentary producer for Hong Kong broadcast company RTHK.

Harry was a natural showman. He was always performingMolly Odell, Harry’s daughter-in-law

“My instinct was that this guy, Harry Odell, is amazing,” says Choi, one recent morning. “And that this guy” – she glances, with a grin, over at Kikabhoy – “is crazy. And that they’re a match. I said, ‘Haider, we have to do this, we cannot waste it.’

“I felt there must be a way to consolidate all these little pieces, floating in the river of history – not just a social-media post that people read and then forget.”

But even for those with no personal connection, it’s an irresistible love letter to the city – informative, funny, nostalgic and unexpectedly touching. In the five years it’s taken for Kikabhoy’s little pieces to consolidate, the river of Hong Kong history has run turbulent and shifted course.

The premiere coincided with the 20th anniversary weekend of Gor Gor’s suicide. As many viewers knew, the street alongside the Mandarin Oriental hotel where he’d died, two minutes’ walk from City Hall, was lined with mourning flowers.

The Latin-American music to which Cheung sashays in the film is played by Cuban bandleader Xavier Cugat, whom Odell brought to Hong Kong in 1966. For Kikabhoy, mining this nugget was a breakthrough, a link to today’s generation as they revisit Wong’s films.

“If I say to people Harry Odell brought in musicians, they say, ‘So what?’ If I say he brought in the musician for Days of Being Wild, they’d go, ‘That’s very impressive!’”

His enthusiasm, ever on standby, means there have been a considerable number of such breakthroughs. He’s an earnest individual – the sort of interviewee who sends minutely clarifying emails post-interview and would, you feel, blend right in at a stamp-collectors’ convention.

After our second meeting, when another late-evening email of appreciable breadth, copied to Choi, arrived in my inbox, she pressed Reply All and wrote: “Now you feel what I felt, way back – midnight and avalanche of information.” Her counterintuitive, yet genius, touch was to place his intense commitment centre stage as he seeks his quarry.

Both of them agree it was a tricky decision. Choi had been making short, award-winning documentaries for RTHK’s flagship programme Hong Kong Connection since 2011. An early plan had been to do a short film, maybe for RTHK’s educational department.

Soon Choi realised what she had in Odell (“a treasure trove”) and began to dream bigger.

She took Kikabhoy’s voluminous research, boiled it down and wrote the script. When she’d arranged everything in sequence, however, it felt inert.

The trouble with Harry was that he needed an additional, living, sidekick. She worried that, as she puts it, “Haider is not the kind of person who can be blah-blah-blah to the camera, he will be uncomfortable.” But she insisted he try.

Choi: I exploited you, I tortured you.

Kikabhoy (quietly, smiling): You sacrificed me.

Me: Was it torture?

Kikabhoy (giving the notion of careful consideration): I was reluctant … We did actually think about who else would play the role of narrator. But Dora knew what she was doing. In the very beginning, the film was, maybe, more about Odell. But along the way we realised, actually, the discovery process is just as important.

Choi: And at the end – everybody loved Haider! People say, Oh my God, he’s so cute. They’re really moved by the kind of nerdiness, that he’s looking for this guy on Amazon and on jury lists.

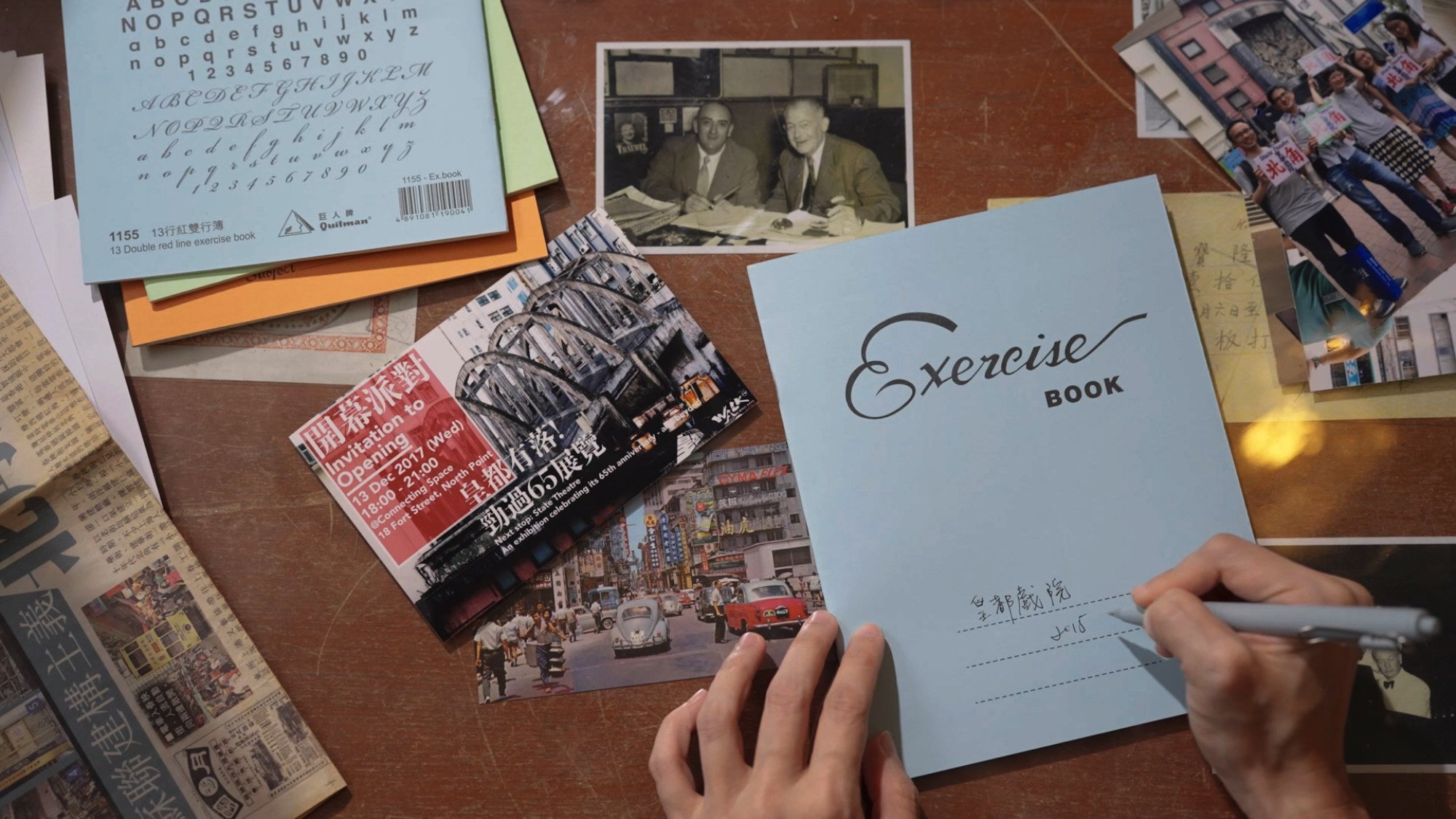

And it’s true – the tone is set when the documentary begins with Kikabhoy opening a school exercise book, the kind you’d find in any Hong Kong stationery shop, to insert photos.

These lined pages become the film’s leitmotif; they’re also a visual homage to Odell, who used a traditional exercise book to keep cuttings about the stars he’d imported to twinkle in the colony. (“When that book is in my hand, I thought, ‘Oh God, this is history,’” says Choi. “So local, so close to us. You can tell the character of Harry Odell – he doesn’t use any fancy album.”)

Soon, Kikabhoy takes a tram to North Point – we glimpse the State Theatre’s iconic concrete-arched roof soaring, like the rib cage of a dinosaur, over King’s Road – and ventures into its ghostly dress circle, a silent hollow hidden behind a false ceiling above the snooker tables. Once, it accommodated audiences of up to 1,300.

“I can find in this space the genesis of Harry Odell’s music dream,” says Kikabhoy, bright-eyed and reverent amid the dust.

“His mission was to bring the best arts and culture from the world to Hong Kong.” (Apart from providing filming access, New World Development had nothing to do with the documentary. Choi and Kikabhoy were emphatic on that point.)

Intermittent clips from a couple of 1960s RTHK radio interviews with Odell, who died in 1975, provide a colourful, if sketchy, outline.

He’d been born Harry Obodovsky in Cairo, Egypt, in 1896, to Jewish parents. The family had moved to Shanghai when he was four.

He’d run away from home at 16, become a tap-dancer in Nagasaki, Japan, emigrated to the United States, where he changed his name (courtesy of a telephone directory), and seems to have picked up a faint New York accent, then fought in France during the first world war, before arriving in Hong Kong in about 1919.

In 1921, he married Sophie Weill, daughter of Albert and Rosie, who owned Sennet Frères, an esteemed watch and jewellery business in the colony. He worked as a stockbroker. They had three sons. “If I could find his descendants, it would be proof he was a real person,” Kikabhoy decides, and the hunt is on.

In fact, when the documentary project began in 2018, Kikabhoy had already tracked down Kudin Odell, Harry’s grandson, in Singapore via a deep trawl of Amazon Marketplace. (Kudin was selling an electronics component fun kit.)

Kudin’s father was Albert, who was manager of the Cathay Organisation, a film company in Singapore; he’d ended up suing the company, which is how he’d met lawyer, and promising politician, Lee Kuan Yew. But Kudin knew almost nothing about his grandfather and said so, apologetically, on camera.

Two months into filming, however, Kikabhoy had his breakthrough: he had located Molly, who’d married Harry’s third son, David. He’d died in 2013 but in December 2018, Molly agreed to fly to Hong Kong from Florida, in the United States.

Even as Kikabhoy waits to meet her at Hong Kong International Airport, under-slept and holding up handmade welcome cards, he tells Choi that the previous night he’d found out Harry had brought a troupe of Soviet artists to the Lee Theatre, in Hong Kong’s Causeway Bay neighbourhood, in 1971.

If Harry’s life is a treasure trove, then his daughter-in-law – supremely elegant, grace personified – is the documentary’s diamond, gleaming on top. She accompanies them to the house in Pok Fu Lam where she spent the early part of her married life living with Harry and Sophie.

It’s called Alberose, in honour of Sophie’s parents; and is now, appropriately enough, the magnificent, retro-furnished home of a famous Hong Kong performer, Cantopop and Mandopop singer Hins Cheung King-hin.

On camera together, Molly and Hins turn out to be world-class charmers. He almost steals the show; every now and then, he shivers with goosebumps induced by contact with such a momentous loop of history.

“I knew this place was sacred even before I moved in,” he confesses. “That’s why you don’t see any of my favourite toys, Godzilla or Gundam figures, here. They just don’t belong to that era.”

Molly fills in further gaps: Harry’s stand at Tai Tam against the Japanese in 1941, his war wound, his incarceration in Argyle Street prisoner-of-war camp.

She talks about Sophie’s bargain with Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke, Hong Kong’s director of medical services, who was going to amputate her husband’s leg: if he saved it, she would, somehow, keep him supplied with medicine.

Eventually, by selling jewellery, and having secret meetings at home with Kiyoshi Watanabe – “the Japanese Schindler” – she is estimated to have saved 200 men’s lives, as well as Harry’s limb.

I kind of fell in love with this guy. He’s so charming, so charismatic. He’s an action man, a workaholicHaider Kikabhoy on Harry Odell

After the war, he decided providing enjoyment for people was a way of putting his best foot forward. In 1969, when he was appointed a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in the New Year Honours List, it was “for services to entertainment in Hong Kong”.

“Harry was a natural showman,” Molly says. “The only time I ever saw him quiet was a day I took him to the doctor. But otherwise, he was always performing. Bless him.” As she stands on the roof of the old Empire, she adds, “I feel blessed that something lives on. It’s nice to have a bit of history because Hong Kong is a city that changes so fast.”

She returns to Florida in January 2019, then, what with one thing and another, in the following months a pause falls on the passion project. In 2021, Choi left RTHK. Without a job, she began to work full-time on the documentary.

She rewrote the entire script, did new interviews with Kikabhoy and she reviewed the many clips she’d assembled from other interviewees. In one of these, Dr Ng Chun-hung, from the University of Hong Kong’s Department of Sociology, had observed that, in the 1950s, Hong Kong “was in love with itself for the first time in history”.

That interview was in 2018. Listening to it again in 2021, post-protests and during a pandemic, it had acquired greater significance. Choi thought the line added – and here she pauses (we’re in another coffee shop, a week later) to consult Kikabhoy in Cantonese – “Yes, it added a new dimension for people to interpret in their own way.”

“Everybody has the feeling of love for Hong Kong at different times in their lives … It’s only because we have gone through so much that we now have the urge to define it.”

The documentary is, undeniably, elegiac. Odell home videos are interspersed with footage of a Hong Kong that’s disappeared.

The film’s double-edged English title is taken from a cinema sign, asking people to wait outside until the previous show has finished: “To Be Continued” is a literal translation of the Chinese characters.

Choi says that throughout his on-camera interviews, “I had to push Haider down a cliff – and then in the last one, which is the conclusion, he was suddenly enlightened. He seized control.”

In that scene, opening another exercise book and recalling how the State Theatre was saved, Kikabhoy says: “We have to write our own history. It is up to us to make our voice heard and count.”

Asked if there will be a follow-up, Choi replies: “We need to take a break from Harry.” Kikabhoy agrees but he sounds wistful.

The premiere has already flushed out tantalising new Odell information, which will increase with the film’s screenings at the Golden Scene cinema in Hong Kong’s Kennedy Town neighbourhood. It’s not exactly the Empire – Kenneth Tsang would categorise it under mosquito – but Haider, who lives in Kennedy Town, and Choi, who was born there, are thrilled.

From Jackie Chan stunt double to Hollywood action director, Andy Cheng’s rise

In her childhood, Choi used to eat at a noodle shop on the North Street corner where the cinema opened in 2021; so the Odell urge to provide a venue for entertainment has not been entirely lost.

A few days after the success of the premiere, on Ching Ming Festival – April 5 – Kikabhoy went to give thanks at Odell’s grave in Happy Valley’s Jewish Cemetery. Later, we go back there together.

He’s the perfect companion for such a walk in Hong Kong. He’s been living so long in Harry’s world, his viewpoint – his empathy – is wonderfully particular. When I ask, he tells me the Kikabhoy family is part of Hong Kong’s tiny Bohra Muslim community, which is based at 69 Wyndham Street, in the city’s Central neighbourhood.

Then he adds: “When Harry’s wife Sophie was little, she used to live at 67 Wyndham Street, next door, so it’s a strange coincidence.”

“Esther died in 1952, seven months before the Empire opened,” he says, gazing at her headstone. “That was a big year in Harry Odell’s life, lots of ups and downs.”

For a while, we stand talking under the trees in the flickering sunlight. History shifts into the present tense. Harry becomes a real person.

“One of the first things I learned through Harry Odell is the word ‘impresario’,” he says. “I love the sound of it. In Chinese there’s no equivalent.” (In the film, the word is translated as “entertainment giant”.)

“I kind of fell in love with this guy. He’s so charming, so charismatic. He’s an action man, a workaholic. He’s very talkative, for sure.”

As is the Jewish custom, he picks up a stone and places it on Harry’s resting place, to let him know he is not forgotten.