- With his first Asian solo exhibition about to open in Hong Kong, Rashid Johnson paints a picture of his artistic journey as we look at his work over the years

The first time Rashid Johnson, born in Chicago, in the United States, in 1977, went in search of his African roots was when he was 19. He was an art student at Columbia College Chicago, curious, but also anxious.

“Something to do with my adolescence, I think – how I grew up, where I grew up – led me to having a little more anxiety than other people,” he says on a chilly January morning in his New York studio.

He often describes its 15,000 square feet (1,400 square metres) as his sanctuary, his safe space, his comfort zone. The street even shares his name: it’s called Johnson, too.

Still underage he’d flown to Senegal, chosen simply because his mother – Dr Cheryl Johnson-Odim, then chair of the history department at Loyola University, Chicago, the first woman and first African-American in that role – had a friend who knew a guy who ran a school in the capital, Dakar.

Johnson, who had grown up in an “Afrocentric” environment, was looking for “his personal origin story”, and says the trip helped him understand aspects of it. But he also saw – as travellers from a diaspora sometimes do when they time-travel to their roots – how ordinary objects back at the wellspring (eg soap, moisturiser, hair products) have been reverently adopted as totems by subsequent generations.

Johnson, who would become known for using shea butter and African black soap in his work, was struck by what he calls this “hybridity”.

Joan Miró’s use of art to explore the meaning of life seen in Hong Kong show

He describes a subsequent trip to Ghana where he went to a village that sold kente cloth to foreign travellers. Kente stoles are often worn by black American students as a rite-of-passage signifier at graduation ceremonies. “I came to realise that the kente cloth was made in …”

He pauses, trying to remember. China? “I think the Netherlands. It hadn’t had this longer history that so many of us in the States had imagined – this cloth that was a kind of conduit to an African experience.

“A big part of what spoke to my interest was the absurdity of trying to identify with a place from which you have been so far removed. Then mistakes are made in the connective rhizomatic explorations.”

Johnson has inherited some of his mother’s scholarly-speak, and, as a result, he comes over more ponderous on the page than in person, when his warm voice often sounds amused. (To the observation that he’s an interesting combination of the comic and the anxious he responds, with a grin, “Maybe the mix of comedy and anxiety is easily defined as neurosis.”)

He once said that growing up the son of an academic made him feel “bright but not capable”, an observation that’s characteristically droll but worried. In 2008, he did a work that combined both tendencies: a mirror spray-painted with the words I Hope I’m Funny.

Once out of Africa, his wry interest in fabric persisted. In 2004, he exhibited The Evolution of the Negro Political Costume.

It consists of three outfits representing three black politicians: a dashiki (former US senator Jesse Jackson), a jogging suit (civil-rights activist Al Sharpton) and a business suit (then senator-elect Barack Obama).

“I think my mother sees my humour,” he says. Does she share it? “She’s more from a generation that recognises it employed these tools to create connective tissues. She doesn’t see it as a slight because it’s not meant that way.

“My humorous, anecdotal response is definitely meant to say, ‘This is fascinating and complicated and our removal from this place has caused us to yearn’.”

These days, the humour is more muted. Last June, he had an exhibition at Hauser & Wirth’s gallery on the Spanish island of Menorca. It was called “Sodade”, after a 1950s song about homesick migrants from Cape Verde, a former Portuguese colony. The title is a Creole version of the Portuguese word saudade – the melancholic longing for a place, imagined or real.

For that show, he created seascape paintings, linen canvases painted with half-moon boats. They bob about at the back of the Brooklyn studio, among his “Bruise” work, his “Broken Men” work, his “Surrender” work. New versions from each themed series will be at his Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong show, which opens on March 20 and is his first solo exhibition in Asia.

In another section of the studio, his assistants – he has “about six or seven”, all long-termers – are carving up a ceramic-and-mirror piece into panels. Or, as he puts it, “decoupling it from its singularity”.

In 2021, The Broken Nine – two long panels, each a 2.7-metre-by-7.6-metre chorus line of gashed faces – was unveiled inside New York’s Metropolitan Opera. As Dodie Kazanjian, director of the Met Opera’s Gallery Met, observed: “Rashid thinks and works on a scale that is operatic.”

Last year, Delta Air Lines’ Terminal C opened at New York’s LaGuardia Airport; a huge (13.7 metres by 4.5 metres) Rashid Johnson mosaic is visible from both the arrivals and departures halls. It has 60 fragmented faces and is called The Travelers’ Broken Crowd.

He creates these “Broken” mosaics from tiles, mirror, black soap, wax and oyster shells. The oyster shells are a glinting reference to the writer Zora Neale Hurston’s line in her 1928 book How It Feels To Be Colored Me: “No, I do not weep at the world – I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.”

During the pandemic, Johnson made a video of himself called Black and Blue, in which he can be seen using an oyster knife (on oysters).

On some of his earlier work, the spray-painted word RUN appears. Has anyone ever shouted at him to run? “Yes! For sure! There were multiple moments when I was prompted to run.”

Yet the way he uses the word is complicated; it can, he says, be a positive prompt. “I ran track as a kid and my brother ran cross-country.” With Johnson, nothing in the world is entirely in black or white and he tussles with it. He’s been in therapy for so many years that he finds it odd when he meets people who aren’t.

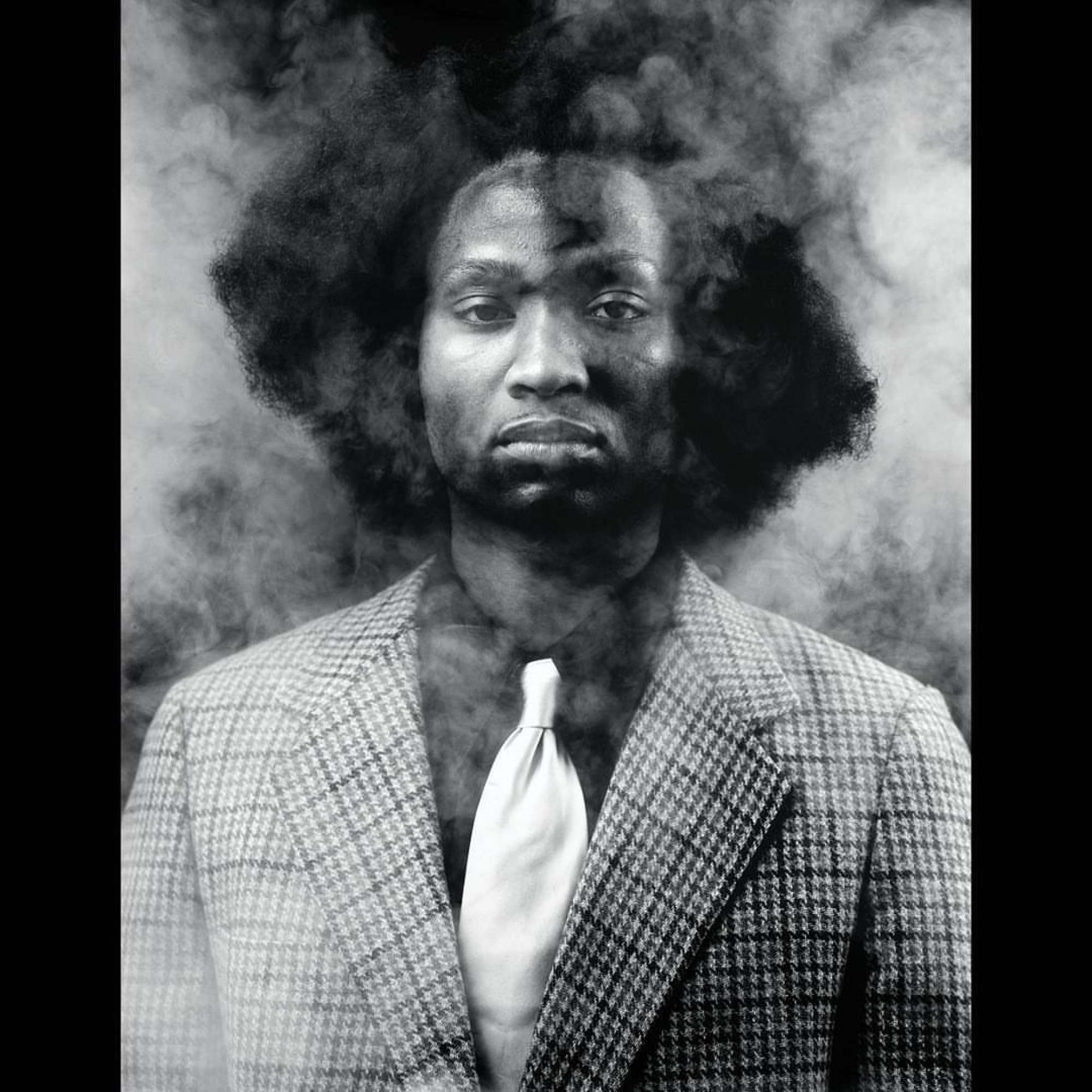

A theme of both escape and escapism runs through his work. In 2008, he founded The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club – or, at least, began a series of photographic portraits of its fictitious African-American members.

That same year he exhibited the first of his “Cosmic Slop” series. These are monochromes made from black soap and wax that have been melted together and, as they solidify, are quickly worked by Johnson into a new surface landscape.

During this interview, he sits beneath the large shadow of one that’s hanging on the studio wall.

“I was 17,” says Johnson. “I just happened to be on the couch when it aired and it blew my mind. It’s about aliens who negotiate with the US government to take African-Americans in exchange for non-renewable resources.” (Spoiler alert: there is no escape. About 20 million darker-skinned black Americans are shipped off in chains.)

Johnson was then living in Evanston, a Chicago suburb that he has calculated, in a radio interview, as being “40 per cent African-American, 40 per cent white and a good healthy mix of Asian and Latino folks”.

In further personal arithmetic, his time was divided between his parents, who’d divorced when he was two. His mother had two other children by different fathers so he has a brother 10 years older and a sister 10 years younger. “At some stage of my childhood, someone said, ‘That’s your half-brother, your half-sister,’ and I was confused.”

Because of the age gap, he spent a good deal of time alone. “I have some only-child tendencies – how I share space, how much time I need to myself to unpack things … I always felt I saw the world in a way that was not necessarily different than how other people saw the world. But it was my own.”

Did that make him lonely? “I mean … maybe. I’ve always struggled with loneliness and what that is for me. I’ve never felt bored or lonely, necessarily. But actions speak louder than words, right?

“I used to drink. I think that was really a result of boredom and loneliness.” He gives a small laugh. “Sometimes I struggle to trust what I think is happening with me and I have to lean into what my experience tells me is happening.”

His father, Jimmy, who had an electronics business, is himself an artist, interested in photography, ceramics, painting, drawing. A similar, wide-ranging approach is mirrored in Johnson’s work, which began with photography.

I think I’m more or less optimistic. But I’m also realistic … Scars going unrecognised is not an effective way to come to terms with them.Rashid Johnson

At 19 – the same year he first went to Africa – he walked into Chicago’s Martha Schneider Gallery, which specialised in fine art photography, and told the owner he had some great work that she must see.

When she asked him to leave, he said if she didn’t look at his portfolio, then other galleries would. She was tickled by his cheek (an early professional example of the power of humour). She looked. She gave him a show.

The feisty attitude doesn’t quite square with the anxious adolescent. “Most artists, whether through delusions of grandeur or deep insecurity, feel that there’s something in the way they see the world that’s worth exploring, right? You hope there’s an audience that kind of understands it as a valuable contribution.”

He acquired a dealer, Monique Meloche. When they met, Meloche told American visual-arts magazine Artnews in 2021, he was “making a lot of Afro-futurist constellation abstract photographs using very culturally relevant objects like chicken bones, cotton seeds, black-eyed peas and barber shavings”. She says she told him she’d take him on if he dropped the chicken bones and went to grad school.

He signed up to do a master of fine arts at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His anxiety increased: he was going through a divorce, feeling financial pressure, questioning the commercial viability of the life he’d chosen, drinking.

Someone suggested going to the Russian and Turkish Baths in Chicago’s Wicker Park. On his first visit, he saw Jesse Jackson costumed in nothing more than a towel. “That bathhouse was incredibly diverse – Mexican business leaders, a small group of ‘little red book’ communists, judges – all men sharing space to sweat and release.

“I didn’t grow up with religion, I didn’t have a church, a synagogue, a mosque, so it was a space for me to meditate.”

It became such a ritual that when he moved to New York in 2005, he sought out the Russian and Turkish Baths in the city’s East Village neighbourhood and, apart from during the Covid-19 pandemic, has been going there almost weekly ever since.

In 2013, he did a literal restaging of Dutchman – a 1964 play by LeRoi Jones, in which a white woman and a black man have a heated argument on the subway – in its steam room and sauna. Members of the audience were obliged to undress and wear bathrobes; they carried bottles of water to sustain them through the performances.

The bathhouse would provide further, and longer-lasting, inspiration. By 2014, he’d stopped drinking. “Very difficult but the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done,” he says. At the same time, major events were taking place in America.

In the summer of 2014, Black Lives Matter stepped out of social media and onto the streets. In June 2015, Donald Trump announced his presidential run. In the next few years his presidency, immigration issues, the #MeToo movement and the death of George Floyd would rattle the nation.

“It did feel like the world was shaking, it really did,” he says. “I was really productive before that time, I made some work that I absolutely love. A lot of my project was looking back, it was about my relationship to certain kinds of histories. And I think in 2014, 2015, as I kind of wake up from the slumber that was brought about by my drinking and other substances, I became focused on a now space – the present.”

In 2015, the first of his “Anxious Men” series appeared. Each one is made of a white ceramic tile – the kind you’d see on a bathhouse wall except handmade – smeared with a mixture of black soap and wax, into which Johnson has scratched an anguished face.

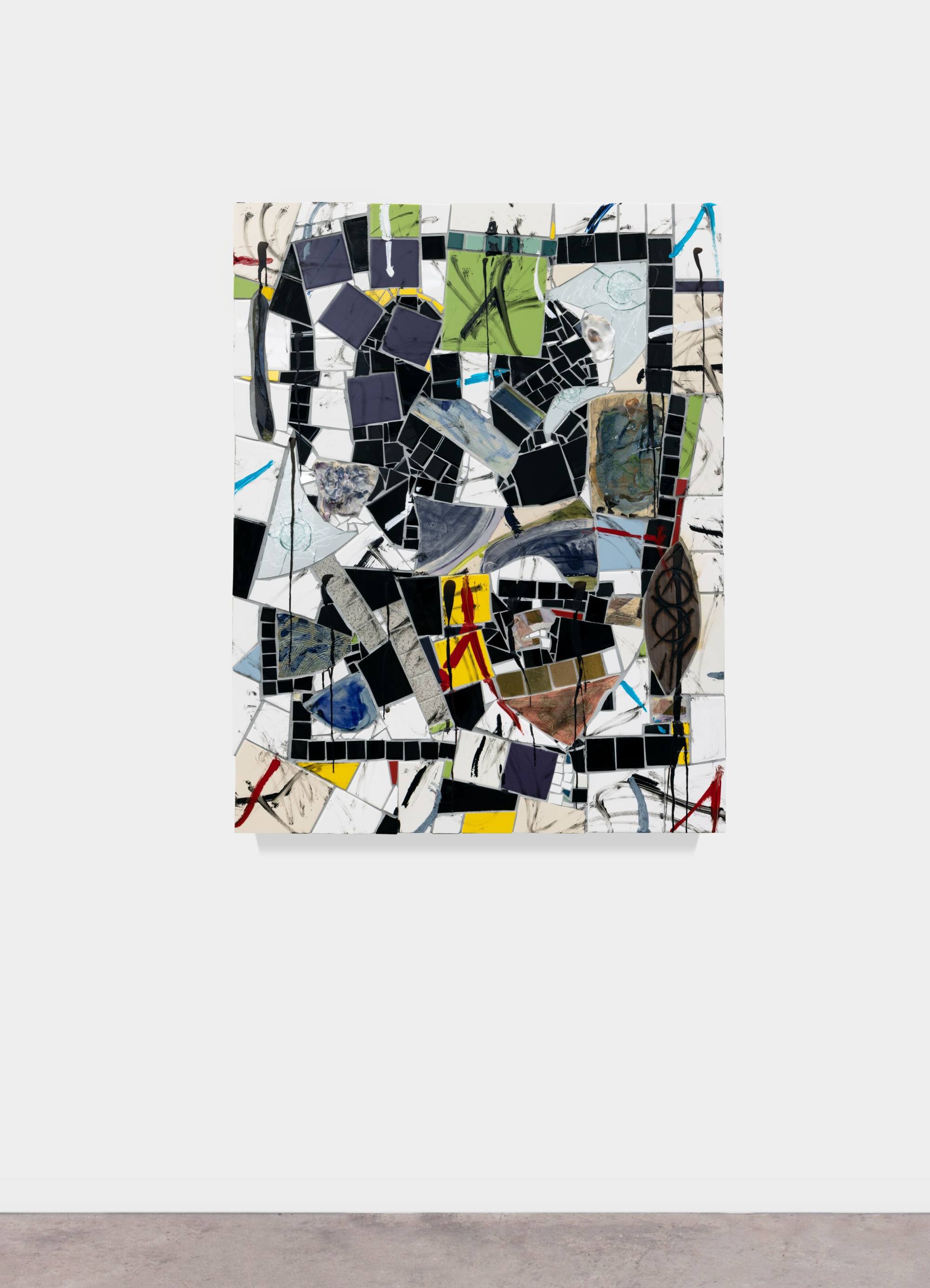

In 2016, “Anxious Audiences”, created in the same way, appeared: a series of appalled bystanders to the chaos. By 2018, he’d moved on to his “Broken Men” series, in which the ceramic tiles and mirrors have been carefully fitted into mosaic patterns.

“With the Anxious Men, the idea was that it was an impermanent condition – however unlikely, you understand the possibility of melting off the wax and soap. The Broken Men came from this idea that the material had developed a kind of permanence, that the set of gestures of this complicated figure were built into the structure of the work.”

That suggests deep pessimism. “I think I’m more or less optimistic. But I’m also realistic. There’s nothing devastating about recognising there are permanent scars. Those scars going unrecognised – optimistically imagined to be not present – is not an effective way to come to terms with them.”

In 2020, at home during the early days of Covid, he began to make his “Anxious Red” drawings: tight scarlet clots suggesting constricted fear and fury.

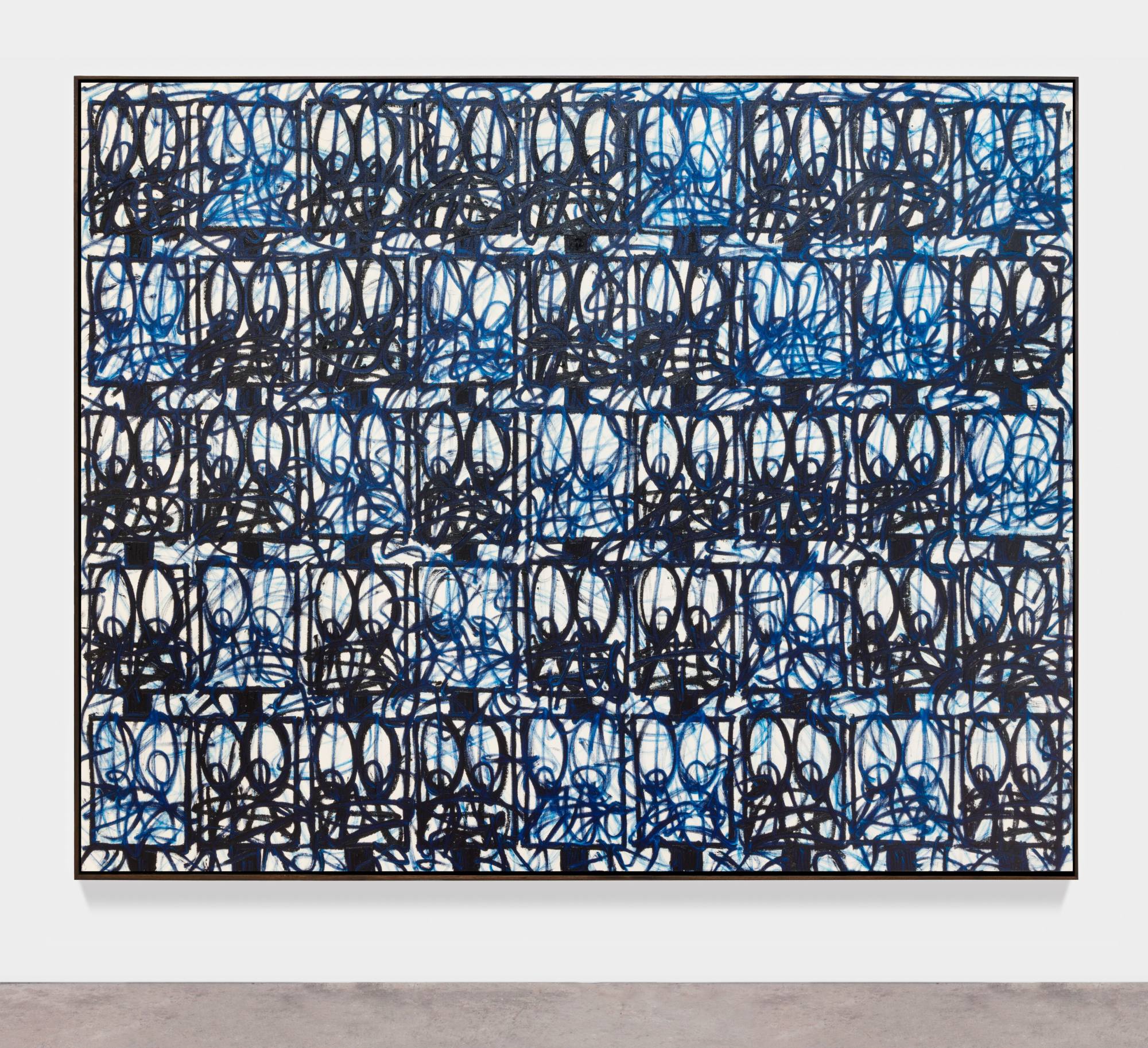

In 2021, he moved on to his “Bruise” paintings: deep blue, slightly loosened coils.

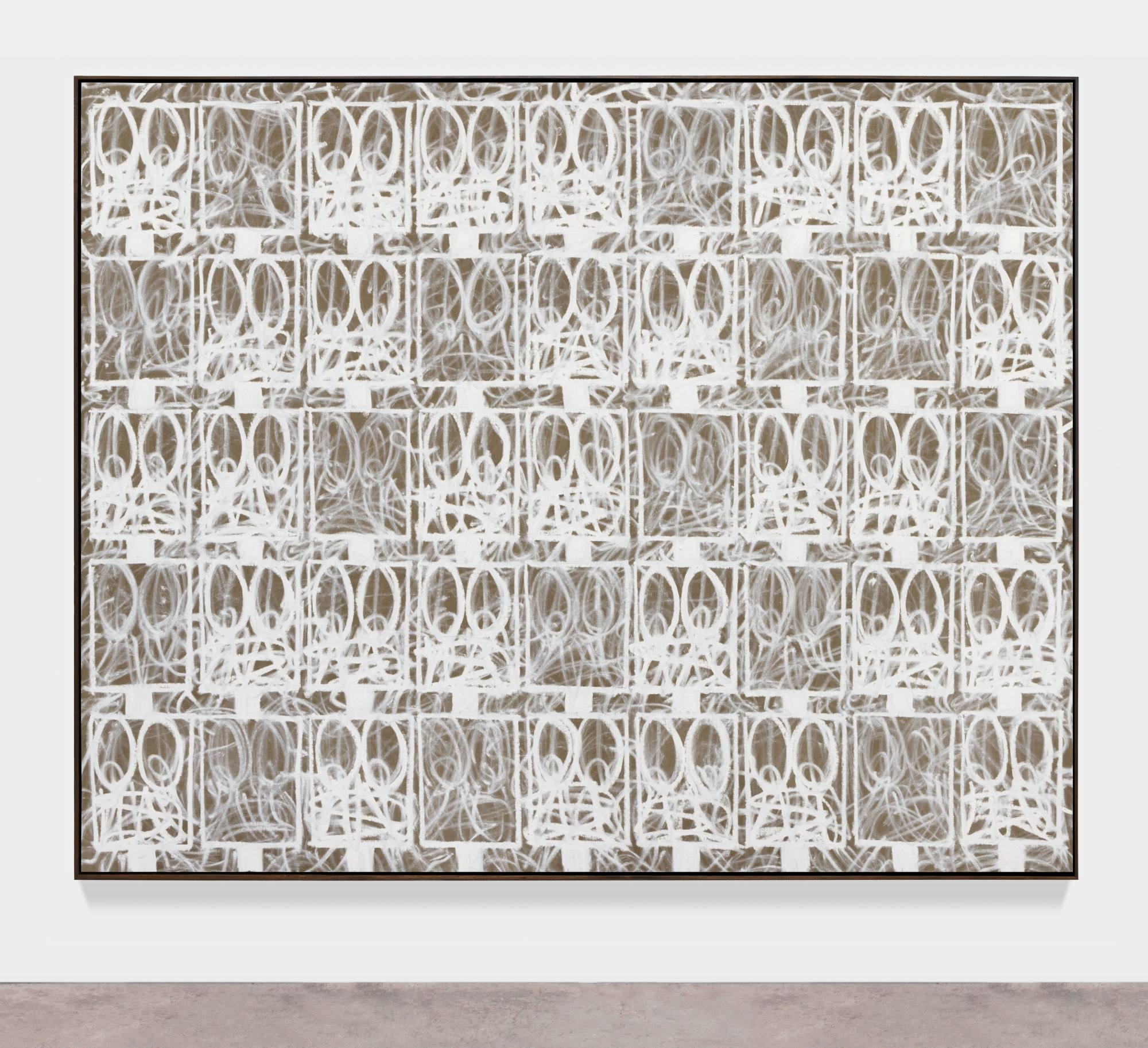

The recent “Surrender” work, painted onto raw linen, is white, theoretically calm but, at least to this viewer, slightly unnerving in its collective blank gaze. (Is surrender a form of therapy? “I imagine it’s the start of the process more than the solution as a whole.”)

He’s called the Hong Kong show “Nudiustertian” – an old-fashioned word for the day before yesterday – because the work explores his recent past.

His wife is the artist Sheree Hovsepian, who was born in Iran and moved to the US when she was two. They met at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and have a son, Julius, 11.

In a 2018 talk he gave at the Aspen Art Museum in Colorado, he mentioned that she believes great art can come from difficult times. He disagreed and went on to say, “I don’t think artists have to be so lazy they need calamity in order to make something interesting – I think that’s a problem”.

Does he still think that? “I do. I think we have too high expectations of complicated times to produce solutions. And I think the expectation that artists can be the wind beneath our wings at these times” – and he gives another laugh – “is really absurd.”

Rashid Johnson’s “Nudiustertian” is at Hauser & Wirth, 15-16/F, H Queen’s, 80 Queen’s Road Central, from March 20 to May 10.