- Pfizer’s vaccine saw it become the world’s most visible pharmaceutical company, but with its stock falling in 2022, investors are impatient for an encore

Pfizer emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic as the world’s most visible drug maker, but its success has left investors impatient for an encore.

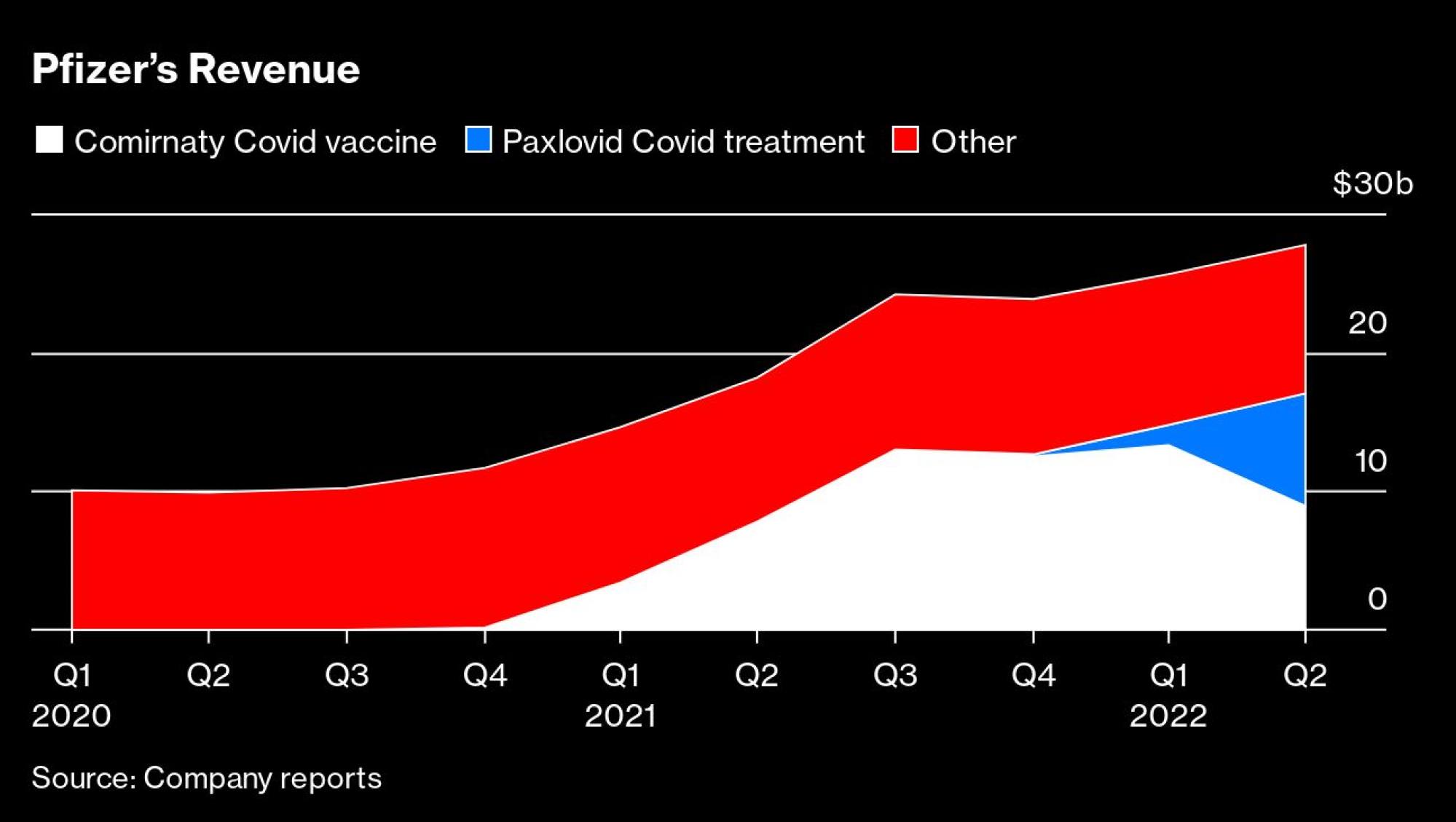

The windfall from the pharmaceutical giant’s Covid-19 vaccine almost doubled its revenue in just one year. And now the shot, coupled with Pfizer’s Covid antiviral pill, is poised to make up more than half of its expected US$100 billion of sales in 2022.

That’s left Pfizer flush with cash – US$28 billion it could spend on the kinds of deals that fuelled its growth into an American colossus.

The pressure is clearly on for Pfizer to show that the muscle it built during the pandemic won’t atrophy. Big Pharma companies don’t normally double revenue so quickly, and nobody expects that kind of growth to continue.

But one thing is clear: Pfizer can’t go back to the sluggish path it was on for years. Its stock has already fallen 25 per cent in 2022 on fears that might happen, trailing the market and other drug makers.

“Pfizer was boring before Covid,” says BMO Capital Markets analyst Evan David Seigerman. “They’re being penalised because either investors don’t see a future for Covid or they don’t have visibility into that future.”

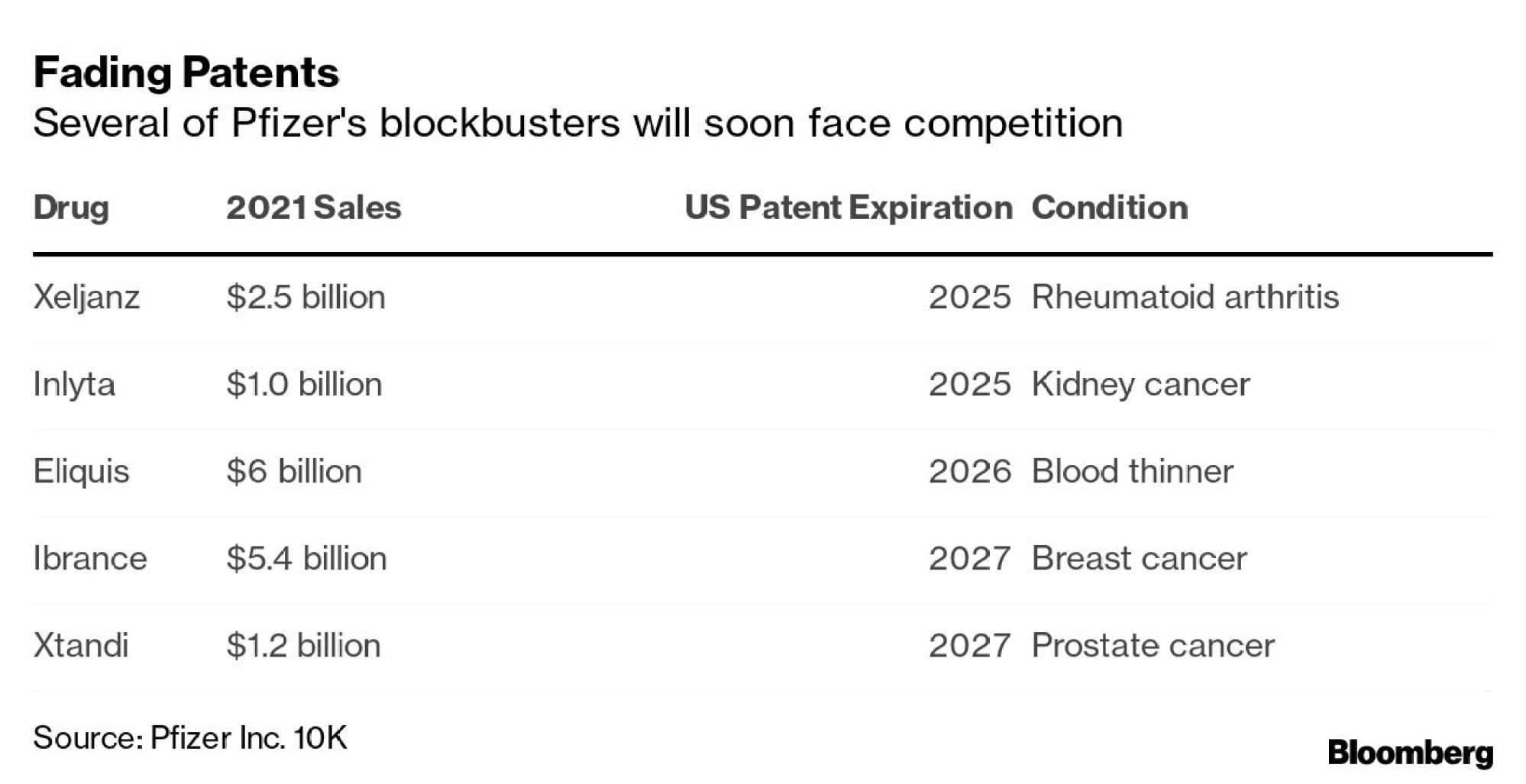

Before the pandemic, Pfizer was in search of its next big hit after going a few years without launching a blockbuster. Several of its current mainstays will soon face competition from generic drugs.

But a problem that might once have been solved by going shopping could now require a different strategy. The megadeals that Pfizer executives have long used to turbocharge growth have become more expensive and more difficult to complete, with interest rates rising and antitrust fervour in Washington.

That’s a problem for a company that has often relied on deals so big that almost no other company could have pulled them off. When Pfizer paid US$90 billion for Warner-Lambert in 2000, for example, one of the assets it collected was cholesterol megahit Lipitor, which sold US$13 billion annually at its peak.

In a search for blockbuster drugs to bolster the company’s pipeline, successive CEOs spent more than US$200 billion on deals from 2000 to 2020, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Even before Covid-19 sickened the first person in Wuhan, China, Pfizer’s new CEO, Albert Bourla, was already embarking on a path that would turn the company into a very different kind of drug maker.

Bourla, who had risen through the ranks and taken the top job in early 2019, saw an opportunity to make Pfizer into a version of the kind of nimble, innovative biotechnology company that it had more usually acquired.

Now, after a two-year-plus detour during which Covid-19 put everything else on the sidelines, Bourla is ready to move on, even if Wall Street is still fixated on the US$37 billion that the shot brought in for New York-based Pfizer in 2021.

“Nobody asked me about how we’re doing with the new products other than Covid,” Bourla said, sounding somewhat exasperated, after an earnings call with Wall Street analysts this summer.

Bourla has promised 6 per cent annual revenue growth for the company’s core business – excluding Covid-19 products – through to 2025. Wall Street believes he can get close: analysts expect that number is more likely to be 5 per cent.

There is no way Pfizer can recreate the conditions that led to this moment. Governments gave companies billions of dollars to speed up Covid-19 vaccine development (Pfizer did not take US money, but its vaccine partner, BioNTech, received US$445 million from Germany.)

This man says he can beat Covid-19 with nasal sprays, not needles

Regulators allowed faster clearance, and the United States government placed billion-dollar orders and invoked a Cold War-era law to hurry along production. Nothing similar is likely to happen again soon.

Covid-19 has left a mark on the pharmaceutical industry, setting off a surge of enthusiasm for and investment in messenger RNA (mRNA), the technology behind the vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna.

Now an mRNA arms race is unfolding, with Pfizer, BioNTech and Moderna facing a legion of upstarts and old-line Big Pharma peers eager to cash in with innovative drugs of their own.

To much of the world, the technology that made Pfizer’s Covid-19 vaccine seemed to come from nowhere. It was actually built on decades of research.

Academics tried, and failed, for years to figure out how to deliver the fragile, synthetic mRNA molecules where they needed to go. Despite advances in the 1990s and early 2000s, no product based on mRNA technology had entered final-stage trials before Covid-19.

Building on the success of that vaccine is a central part of Bourla’s own vision for Pfizer. He has said that he’s “all-in” on mRNA and talked about an abundant pipeline of potential uses for the technology, from a vaccine for flu – which could come to market as soon as next year – to a shot for shingles, cancer treatments and cures for rare genetic diseases.

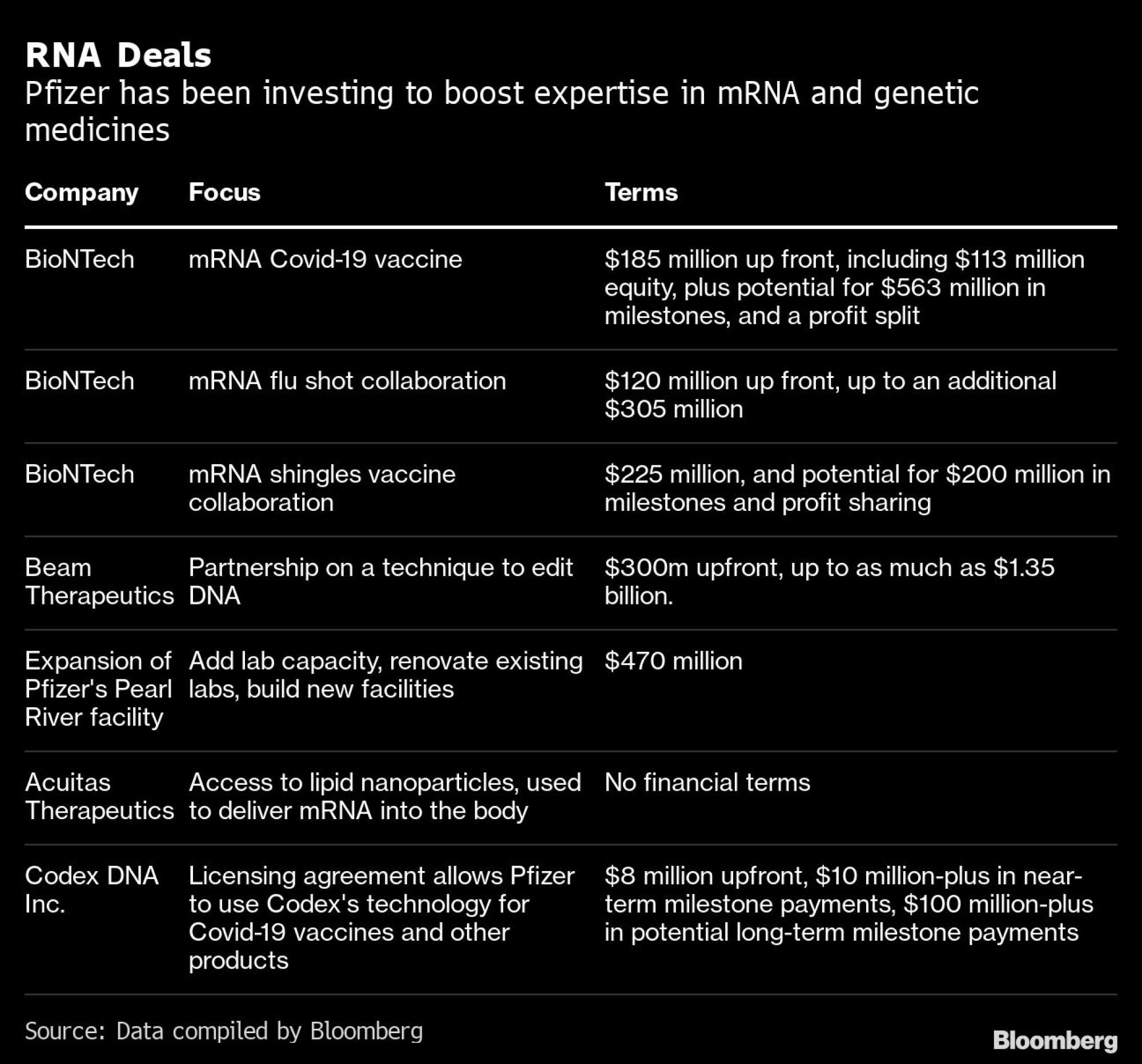

Pfizer has already put some of its capital to work forging alliances with smaller, specialist companies. However, success could take years, and many rivals, including Moderna, are also hard at work on mRNA.

“When Pfizer starts to go after mRNA therapeutics, it’ll find potentially bigger hits, but also more uncertainty,” says Morningstar analyst Damien Conover. “Each time you get a little bit further away from infectious disease – how it’s being used right now – you get further from how the technology has been working.”

Pfizer wants to bring multiple mRNA products to market within five years – an ambitious time frame based on how drug development usually works.

Therapies can take more than a decade to move from a lab into the human testing that determines whether regulators will approve them. About 90 per cent of drug candidates fail in clinical trials.

That doesn’t mean labs in the US aren’t trying, leading to a fight for scientists.

“Students and trainees are being bombarded,” says Daniel Anderson, a chemical engineering professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, adding that many of his students have dropped out to launch companies or join established and emerging drug makers.

Some 43 private companies working with mRNA technology have raised about US$1.6 billion in funding in the past 12 months, according to Pitchbook data. Then there are also the big publicly traded giants such as Moderna or BioNTech that are pioneers in the space.

Tell me one industry where disruption has happened by a large incumbentModerna CEO Stéphane Bancel

To compete, Pfizer has been elevating its in-house mRNA experts, including Kathy Fernando, a 44-year-old pharma executive who launched her career studying the technology.

In 2006, she completed her PhD dissertation on developing an RNA vaccine for HIV. She later left academia for business consulting and joined Pfizer in 2014.

During the pandemic, Fernando was named Pfizer’s head of mRNA scientific strategy and worldwide research and development operations.

“We don’t aim to be the company with the most mRNA programmes in our portfolio – we’re more selective,” Fernando says. Much of the battle is knowing where to start.

Fernando breaks the question into three parts: evaluating technology, biology and manufacturing.

“The second and third parts – biology and manufacturing – are what differentiate us,” she says.

It is a hint that Pfizer may not lead in technology, but the company can successfully bring a product to market. Pfizer says that as of September 4, it has shipped 3.7 billion doses of its Covid-19 vaccine to 180 countries. Moderna declined to comment on how many doses of its vaccine have been distributed.

Forty kilometres (25 miles) north of its New York headquarters, Pfizer is spending almost half a billion dollars to upgrade its Pearl River vaccine R&D campus.

The site – 135 hectares close to several state parks – is the clearest physical manifestation of the Pfizer that Bourla envisions: home to cutting-edge laboratories and more than 1,000 staff that were pivotal to the development of the Covid-19 shot.

The money will be used to expand and update the labs, along with adding some typical corporate perks such as a new cafe and a gym.

Pfizer has also turned to external mRNA advisers to pressure-test its strategy, especially when new products are on the table. Drew Weissman, a University of Pennsylvania professor in vaccine research credited with developing the mRNA technology used in the Covid-19 shots, is among those who have been tapped for their guidance.

Weismann says Pfizer puts “as many as 30 people together and has them battle out ideas over a one-day or two-day event”.

Pfizer’s rivals are making similar moves, and they are looking beyond just mRNA at other RNA- and DNA-focused medicines. Pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly is hiring talent and scouring for such deals, and it is building a new US$700 million facility in Boston, the biggest biotech hub in the US. Dan Skovronsky, Eli Lilly’s chief scientific and medical officer, says there’s no way one company will dominate this space.

“It starts with a couple of players, but the technology becomes adopted by all of pharma and eventually becomes one of the pillars of how they make drugs,” Skovronsky says.

Then, of course, there is Moderna. At its peak, the Cambridge, Massachusetts-based company ballooned to a US$190 billion market valuation after its Covid-19 shot, Spikevax, hit the market.

Moderna’s CEO, Stéphane Bancel, is sceptical that Pfizer can become a bastion of mRNA innovation.

“Tell me one industry where disruption has happened by a large incumbent,” he said in an interview at Moderna’s R&D day in Boston in September. “Pfizer did an amazing job getting the product to development and manufacturing scale. We did the same with no help from a Big Pharma company.”

A spokeswoman for Pfizer says the vaccine was based on BioNTech’s proprietary mRNA technology and that the company is confident in the intellectual property supporting the shot and will defend itself against the allegations in the lawsuit.

RNA is a fantastic platform, but it won’t solve everything, right? To think a single technology will solve all your problems – well, it never doesKathrin Jansen, Pfizer’s recently retired head of vaccine R&D

Beyond the fight with Moderna, there are questions around how much further Pfizer can get in mRNA without relying on the partner that helped it develop the vaccine in the first place.

“Pfizer is now the largest manufacturer of RNA vaccines in the world,” says Weissman. “But they were reliant on BioNTech for that knowledge of the platform.”

Bourla has been trying to change the perception that Pfizer needs BioNTech to advance its mRNA strategy. “We don’t need to work with them,” he said in an interview in early 2021, describing it as a “fantastic partnership”, but one that wouldn’t prevent the company from charting its own course.

So far, Pfizer says it has spent more than US$2 billion on mRNA projects, a pittance compared with its mammoth cash pile. The company has the capacity to spend at least US$150 billion on deals by the end of this year, BMO’s Seigerman wrote in an April note.

But the deal-making landscape has changed significantly since then, as interest rates shot up and inflation spooked credit markets. Global merger and acquisitions volumes have slowed to a trickle: just one deal valued at more than US$10 billion has been announced since June.

Then there is the problem of what to buy. Pfizer executives have said they are expecting to do enough deals to add some US$25 billion in sales by 2030. They will have to do it without attracting too much attention from policymakers in Washington, where antitrust enforcers have been eyeing tougher merger rules to tackle concentration across industries.

Pfizer may be all-in on mRNA but that does not mean it isn’t doing a lot of other things, too.

Its most promising drug candidates include a vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which kills or hospitalises more than 100,000 older adults each year in the US, as well as a therapy for obesity and diabetes, and autoimmune and cancer treatments.

The magic mushroom pill business goes into overdrive

Though these potential blockbusters tend to get less airtime during investor presentations, and fewer questions, they are critical to Pfizer’s post-Covid growth story.

Still, the Covid-19 market alone could keep bolstering Pfizer for several more years. Bourla has pledged that the company will continue to dominate the market with next-generation annual boosters, tailored to the latest variants.

That market is shrinking. Uptake of the new Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna boosters is strikingly low, with only 2.7 per cent of the eligible US population having received one of them as of September 28, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

Seigerman still sees the potential for regular demand among over 50-year-olds, which in the US alone would be a US$7 billion-plus annual market for Pfizer, a figure he describes as “exciting to have on the balance sheet”.

“The question is for how many years?” he says. “There’s not a lot of optimism that the market will fill out.”

Demand for the updated Covid-19 booster has been low, and analysts expect Pfizer’s overall revenue from the vaccine to start dropping sharply: from US$33.2 billion this year to US$10.5 billion in 2024.

For Pfizer, mRNA is unlikely to be a panacea. Even if it hits its ambitious drug development targets, persuades people to keep getting Covid-19 shots and introduces a groundbreaking new flu or shingles vaccine, it will still have the same competitors, pricing pressures and regulatory hurdles it faced before.

“RNA is a fantastic platform, but it won’t solve everything, right?” says Kathrin Jansen, Pfizer’s recently retired head of vaccine R&D who first suggested that Bourla pursue an mRNA shot for Covid-19.

“To think a single technology will solve all your problems – well, it never does.”