- Often dismissed as fanciful and racist, L. Ron Hubbard’s stories of his trips to Asia as a teenager in the 1920s might not all be as made up as once believed

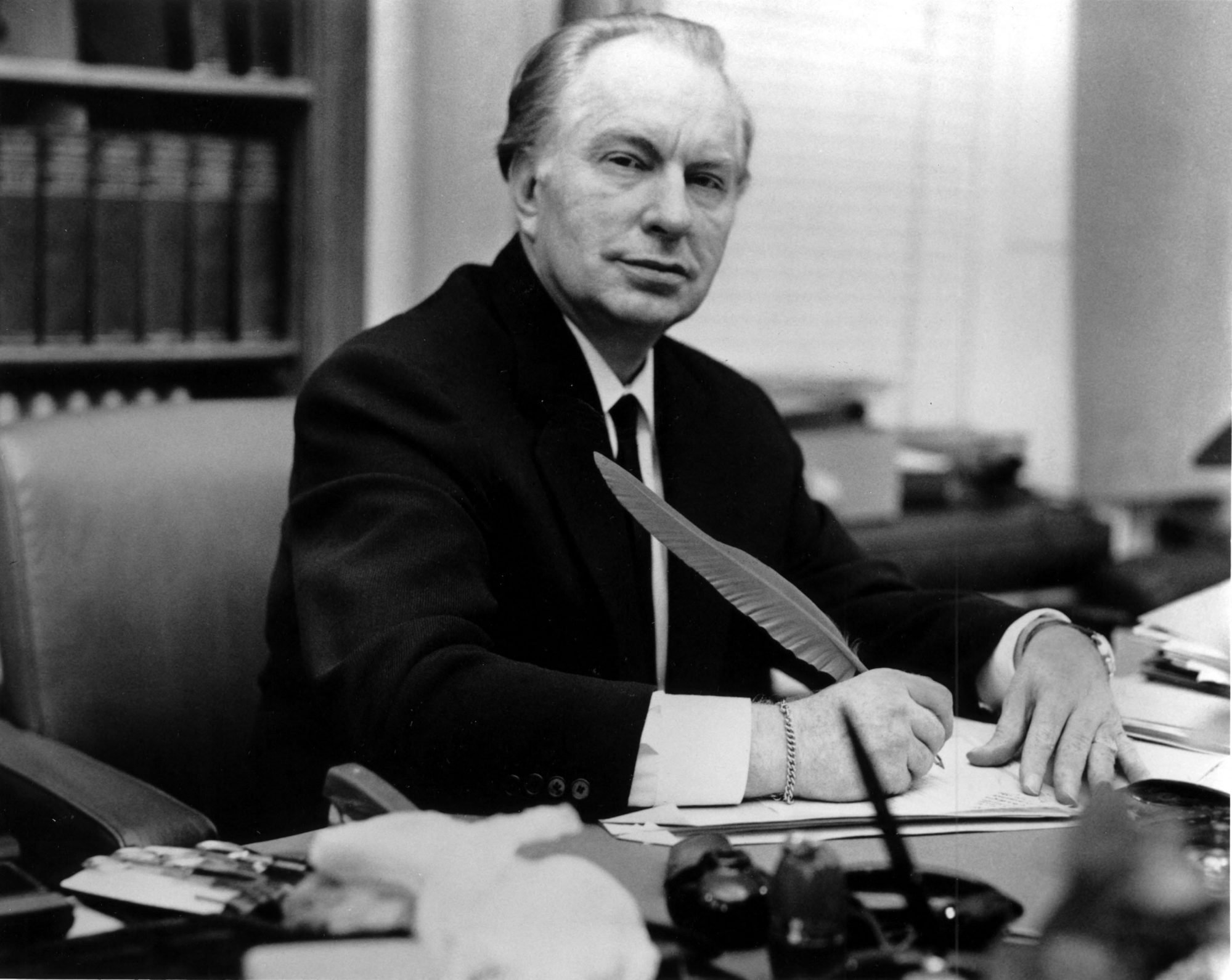

Today, the name L. Ron Hubbard is automatically referenced as the founder of the Church of Scientology, the celebrity-laden super-rich pyramid faith that has spread around the world with controversies and scandals following at every step.

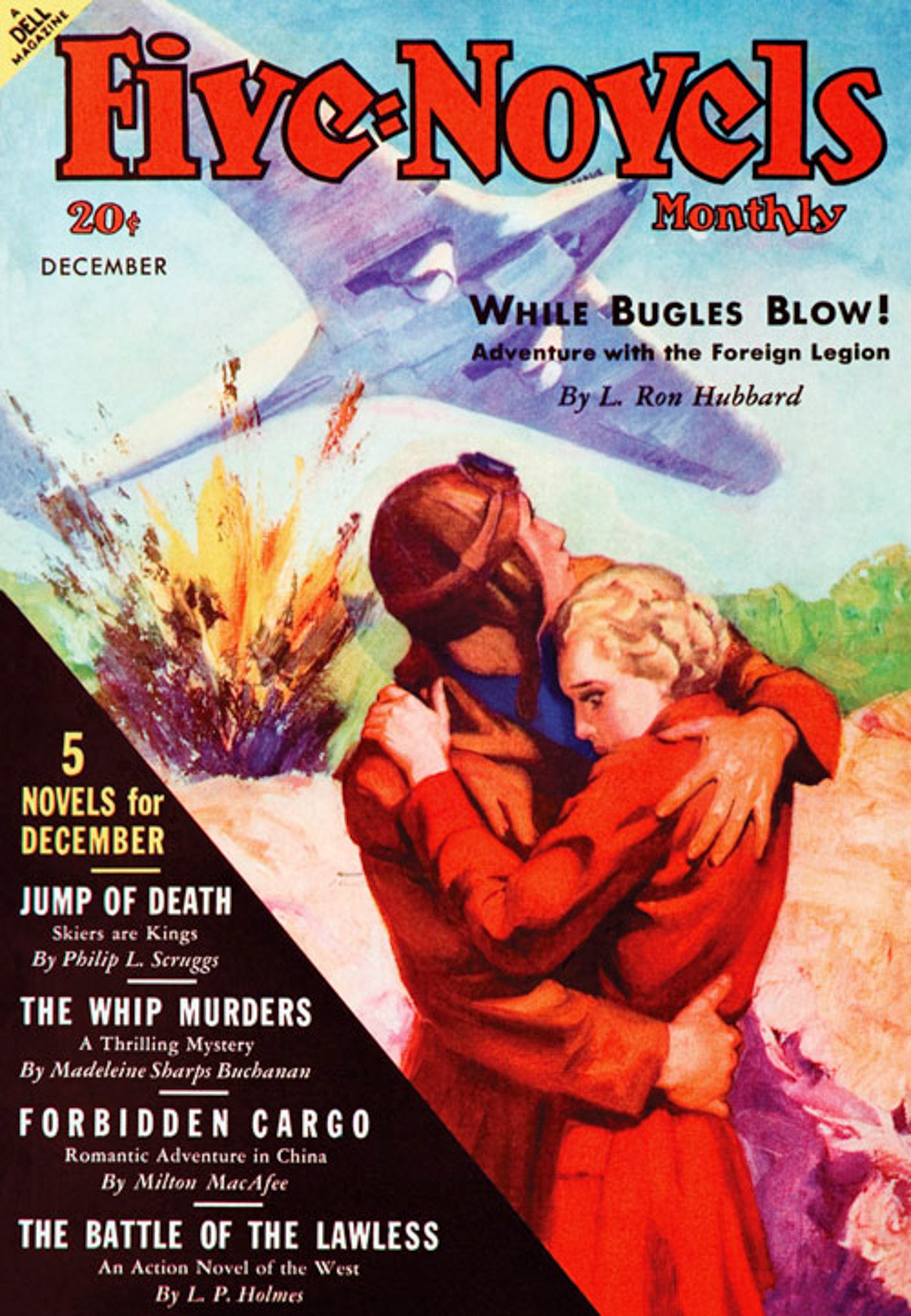

That the religion’s tenets, mostly of attaining consciousness commensurate with a gang of intergalactic superbeings, were dreamed up by Hubbard is well known. Perhaps it is more affirming than surprising then, to find that when spending a few idle hours flicking through old American pulp fiction magazines of the 1930s – Thrilling Adventures, Five-Novels Monthly, Detective Fiction – you’ll often see Hubbard’s byline.

He was a regular contributor to more than half a dozen bestselling publications available on every news-stand across the United States. You may also come across some pretty good stories from authors Michael Keith, Charles Gordon, Bernard Hubbel, Barry Randolph, Humbert Reynolds … a few of the dozen pseudonyms Hubbard used when writing detective stories, Westerns, sci-fi, or regaling readers with the exploits of French Legionnaires, ace airmen and American mercenaries. All of which earned him fame, fortune and a great deal of notoriety, to the tune of 19 New York Times bestsellers and more than 350 million books sold.

Having grown up in the first decades of the 20th century in Montana, Hubbard daydreamed of visiting Asia and becoming a writer. In the 1920s, he did visit China and then, in the 1930s, became one of America’s best-known pulp fiction writers, often drawing on his experiences in the Far East.

Some of the characters he described seem to be pure pulp fabrications, but on closer investigation, it appears Hubbard may not always have been exaggerating as much as expected.

More than a dozen of Hubbard’s short stories (of the well over 150 that were published) were set in China, and they are among his best. In The Devil – With Wings (1937), a British flying ace battles the Japanese from Shanghai to Vladivostok. In Spy Killer (1936), an American seaman falsely accused of murder escapes into Shanghai’s old town.

We head to Mongolia in The Trail of the Red Diamonds (1935), with an American adventurer searching for Kublai Khan’s lost jewels and battling Chinese bandits. In The Falcon Killer (1939) an American airman fights warlord mercenaries and Japanese spies across China. And in perhaps Hubbard’s most overtly detailed and political fiction, The Red Dragon (1935), a former US Marine attempts to subvert the Japanese occupation of Manchuria by reinstating the Chinese emperor.

Hubbard’s China-set stories are fast paced, a little cynical and portray a country embattled by myriad warlord skirmishes and the Japanese annexation of Manchuria. His relationship with China is complicated by the myths and legends that swirl around him, and any confidence about his own biography is tricky. The Church of Scientology perpetuates its own official bio of Hubbard, which differs significantly from other accounts, and many details of Hubbard’s youth remain disputed.

What we know for sure is that Lafayette Ronald Hubbard was born in 1911 in Nebraska and raised largely in Montana, in a US Navy family. This meant he moved around a lot owing to his father’s various postings, including a lengthy stint on Guam, an island in the western Pacific controlled by the US Navy after the Spanish-American War of 1898, operating mostly as a way station between the US and the Philippines (another American acquisition from Spain).

In an “About the Author” introduction to his influential sci-fi novel Battlefield Earth (1982) – which would become a 2000 film starring one of Scientology’s most high-profile acolytes, John Travolta, and garner a 3 per cent rating on Rotten Tomatoes – Hubbard claimed his first trip to Asia was in 1927.

Writing in the third person, Hubbard purports to have “worked aboard a coastal trader which plied the seas between Japan and Java. He came to know old Shanghai, Peking, and the Western Hills at a time when few Westerners could enter China”.

The family apparently called in at Japan, the Philippines, China and his father’s base on Guam. It all sounds like something from a Joseph Conrad novel, which may indeed have been Hubbard’s inspiration. Conrad’s Asian seafaring adventures had been regularly serialised in the American story magazines Hubbard would have read as a boy.

They smell of all the baths they didn’t take. The trouble with China is, there are too many chinks here.Excerpt from Hubbard’s personal journal from 1928 and 1929

This oft-republished introduction, and other interviews with Hubbard, claim a series of fantastic adventures across pre-World War II China. If we are to believe Hubbard’s accounts, he spent time interviewing lamas on spiritual matters and watched them meditate (and levitate). He hung out with Mongolian bandits, Siberian shamans and a magician he claimed was called Old Mayo, the last in a long line of illusionists stretching back to the court of Kublai Khan.

Perhaps most fancifully, Hubbard claims to have met and befriended a certain “Major Ian Macbean of the British Secret Service”. Macbean, Hubbard related, was the “regional head” of MI6 in China. He apparently took Hubbard under his wing and into his confidence, introducing the political neophyte to the “Great Game” of Asian espionage and the geopolitical tug of war between China, Japan and Britain.

Hubbard claims to have faced many dangers in the company of Macbean, including an “encounter with Cantonese pirates, the engineering of a jungle road across Guam’s denser corner, and the evening he decked an Italian swordsman named Giovinni”. (Although not before Hubbard took a sabre cut across the left cheek and Macbean nearly lost a hand.)

All good background for an author out to build his own mythology, but which, if any, of these tales are true?

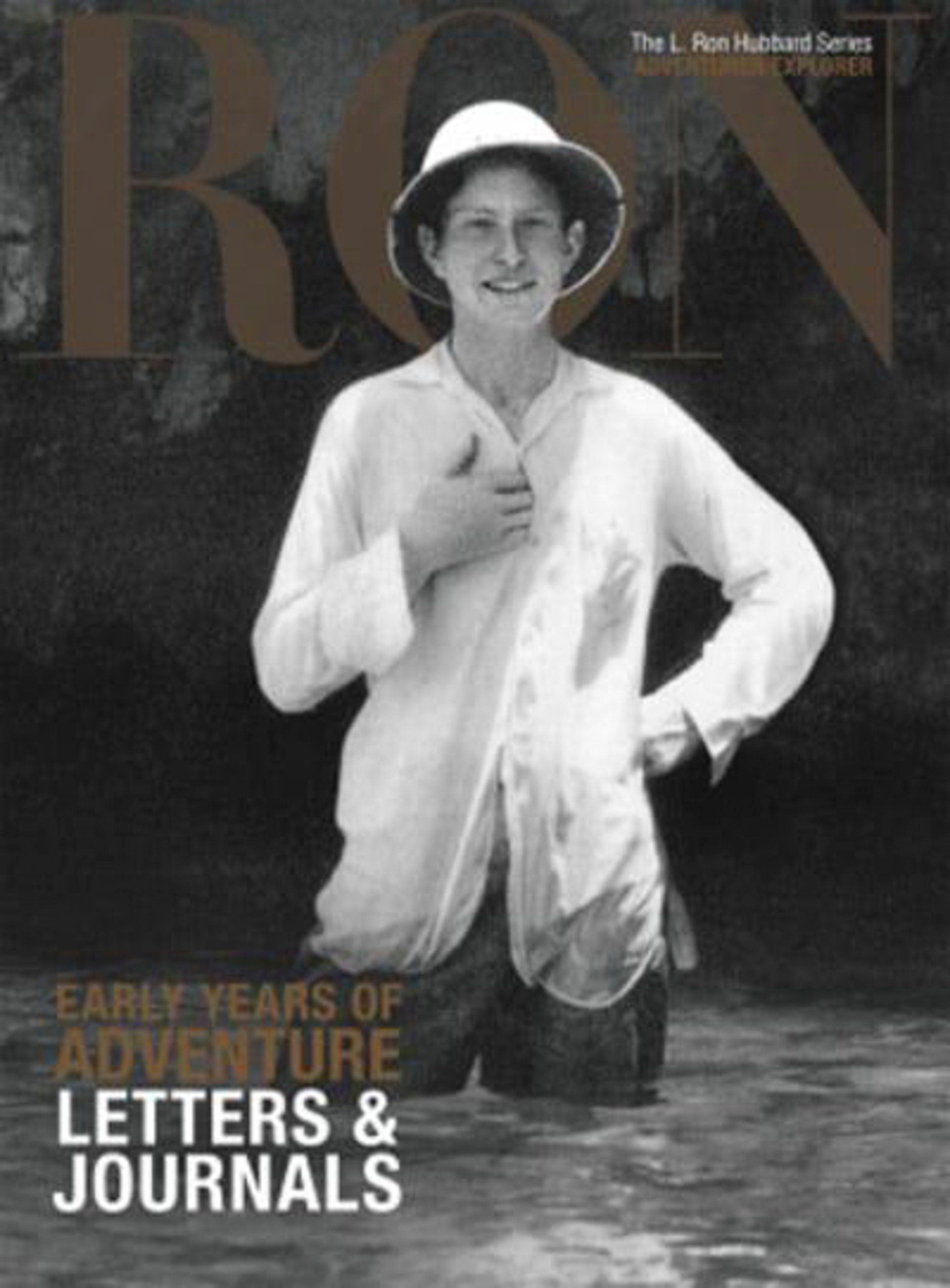

Hubbard’s “Asian Diaries”, a collection of letters and journals published in 2012, have it that the young Hubbard travelled twice to China. The first trip was from May to July 1927, when he was 16, but not working passage on a freighter, rather accompanying his mother from home to see his father at the US naval station on Guam.

It was a rather roundabout trip. Initially the pair took a passenger liner, the Dollar Line steamship President Madison, from San Francisco to China via Honolulu, Yokohama and Kobe. Hubbard played shuffleboard and deck golf across the Pacific.

The liner called at Shanghai, sailing up the Yangtze and into the muddy Huangpu River. Hubbard noted sampan beggars and desperate labourers looking for daywork along the waterfront, and he and his mother toured the foreign settlements, taking in the usual exotic sights – turbaned Sikh traffic cops, rickshaw pullers, British Tommies and Japanese Bluejacket Marines alongside American soldiers. They had tiffin at the Palace Hotel on the Bund, and his mother shopped for tapestries and rugs.

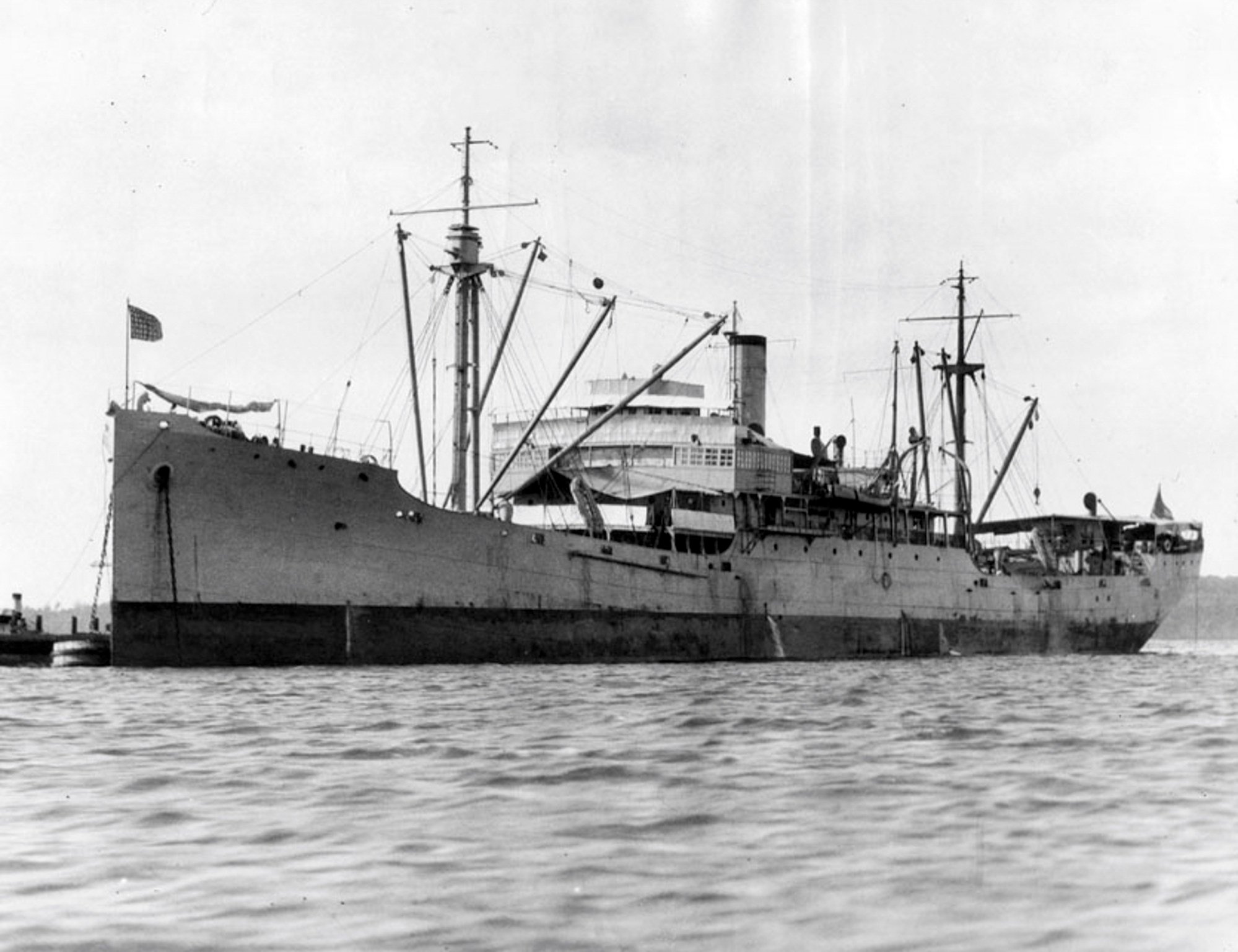

They moved on to Hong Kong, suffering both extreme humidity and a tropical downpour in the British colony. From there to Manila, where they transferred to the rather less comfortable US Navy transport vessel the USS Gold Star, which took them to the base on Guam. “Seven days of rough weather and rotten grub,” Hubbard noted in his diary.

Hubbard returned home to America that summer, via Wake Island and Hawaii, to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. He travelled alone on the USS Nitro, a ship that plied the waters between US Navy bases carrying men (and dependents), ammunition and supplies. His diaries suggest a young man enjoying travelling alone, studying, climbing up to the crow’s nest and making friends with the “Acey-Deucy” crew.

Hubbard then returned to Asia for a second time in June 1928, now 17 years old. Here the record divides. His diaries (published by the Church of Scientology) claim he signed aboard a “working schooner bound for the Malay Peninsula”. Shipping records record that he travelled aboard the USS Henderson, a regular US Navy transport, but there are photographs of Hubbard aboard a schooner, the 116-ton Mariana Maru.

On this trip, Hubbard’s journals say he visited Beijing sometime between September and November. He notes the disruption on the train lines from Tianjin to Beijing and around northern China after the assassination of the warlord Zhang Zuolin, killed when his personal train was derailed by an explosion on the South Manchuria Railway outside his base of Shenyang.

According to Hubbard’s diaries, owing to the disruptions, it took him 16 hours to travel the 85 miles from Tianjin to Beijing by train. All good fodder for his young mind. In one of his first China-set pulps, The Green God (1934), we join a US Marine lieutenant besieged by warlord mercenaries in Tianjin.

Hubbard was not instantly sold on the delights of Beijing, and the city is never fondly described in his later fiction. It was a cold winter, with repeated dust storms whipping down from the Gobi Desert. Stagnant pools of water in the rutted hutongs froze, making walking around a treacherous activity.

He stayed in the city’s YMCA and rendezvoused with his parents, who arrived from Guam. They did the sights, the touristy “rubberneck stations” he called them, and young L. Ron was not overly impressed – the Temple of Heaven (“gaudy and crude”), the Yonghe “Lama” Temple (“miserably cold and very shabby”), the Summer Palace (“a decaying witness to frivolity”).

The Temple of Confucius impressed him more, as did the Forbidden City (although “very trashy-looking”), where he ruminated on the fate of the last emperor, Puyi, whom Hubbard put back on the throne of China in his pulp story The Red Dragon, as mentioned above.

The family took an excursion to the Great Wall, where “the Wall straggled miles before me, broken in places, cut here and there by sandstorms”. They saw the Nan-K’ou Pass (now the Juyong Pass), then quite a remote and impressive location. Returning to Beijing, Hubbard noted the hardy camels and the caravans moving through the arches in the Great Wall towards the city.

Hubbard claims to have travelled to other parts of China and Asia, though the details in his published Letters & Journals are sketchy and inconsistent. He eventually arrived back in America in mid-1929, when he began preparing to study civil engineering at George Washington University.

The teenage L. Ron Hubbard had seen Hong Kong, the foreign enclaves of Shanghai, the former imperial city of Beijing. In his pulp stories a half-dozen or more years later, while he certainly exoticises the place for literary effect, he also shows some degree of sympathy for China in its battles with Japan. However, he never seems that impressed. Indeed, his diary entries suggest a downright dislike.

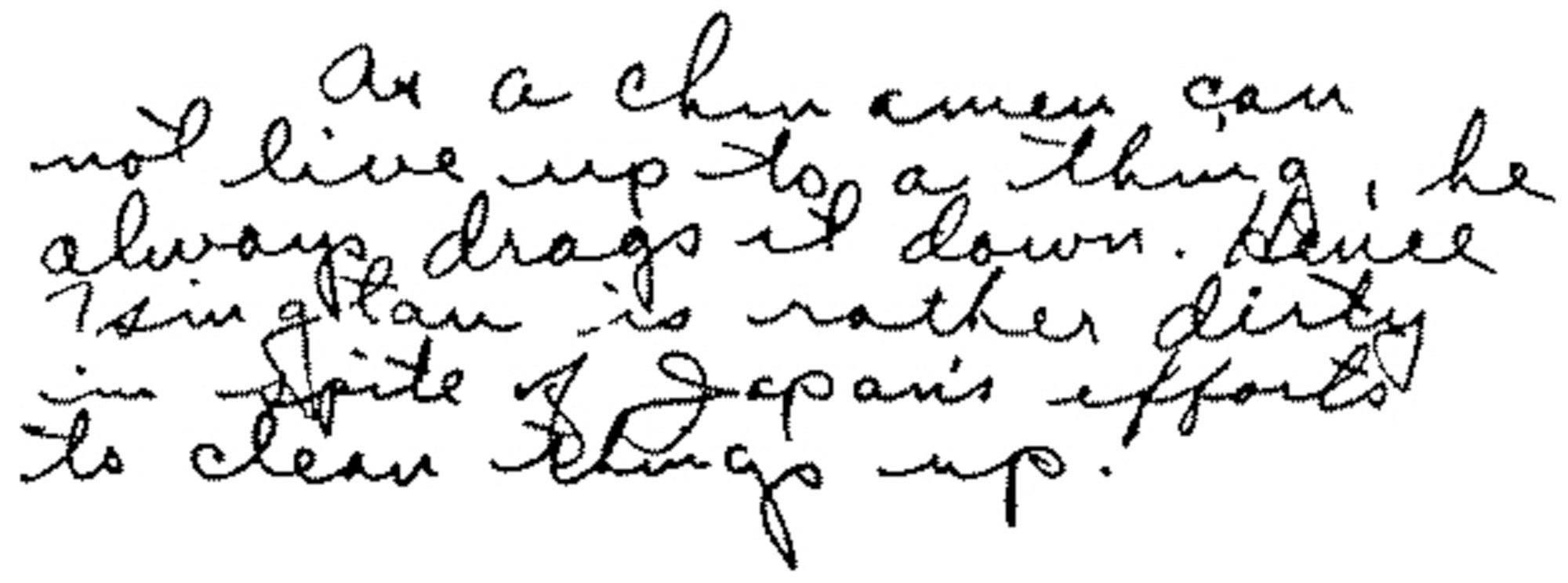

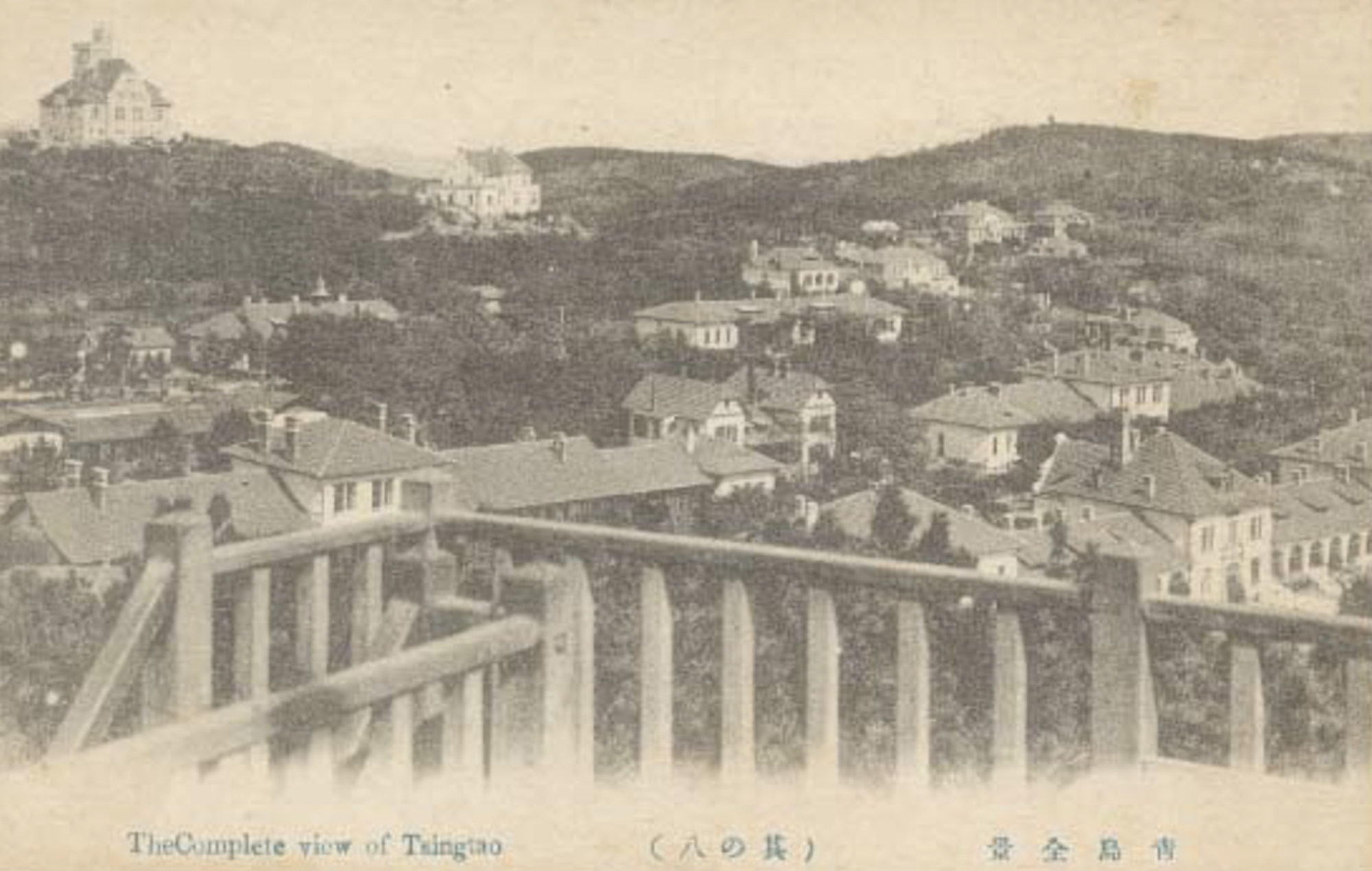

Hubbard’s personal journal from 1928 and 1929 – as opposed to his later interviews and pulp stories – replicate contemporary racist attitudes. He refers to the Chinese as being “gooks”, “lazy” and “ignorant”. Visiting the former German concession of Qingdao (Tsingtao), in Shandong province, he noted in his diary: “A Chinaman cannot live up to a thing, he always drags it down. Hence Tsingtao is rather dirty in spite of Japan’s efforts to clean it up.”

The Japanese had occupied the port in 1914, to China’s fury. But it is not international geopolitics and empire jockeying that concern Hubbard here, rather the Chinese people themselves. “They smell of all the baths they didn’t take,” he writes. “The trouble with China is, there are too many chinks here.”

Over the years most people have brushed off as fantastical inventions many of Hubbard’s claims about his China sojourns in the introduction to Battlefield Earth. Everything else about the Church of Scientology – its beliefs, rituals, operations – seems so opaque, exaggerated and bizarre that it has been easy to just dismiss all of Hubbard’s oeuvre as hyperbole. But…

Despite it all sounding outlandish, there was a Major Ian Macbean assigned to the British Embassy in Beijing in the late 1920s. He is listed in the China Year Book for 1929/1930 as a “cypher officer” within the Legation. Macbean was responsible for coding and decoding incoming and outgoing correspondence from the embassy to Britain’s other consulates and military posts around China as well as, presumably, back to London.

How the young Hubbard met Macbean we cannot be sure. Perhaps he only heard tell of him. Further digging around Britain’s National Archives, at Kew in London, reveals a Major Ian Gordon Macbean served with the Sherwood Foresters (the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Infantry Regiment) from around 1910 and during the first world war.

We are offered a glimpse of Macbean’s life in the autobiography of his wife, the English ballerina Phyllis Bedells. She does not provide a wealth of details – her book, My Dancing Days (1954), is after all about her and not him – but we get tantalising glances that seem to back up Hubbard’s narrative.

Macbean was the product of a private British education – Repton School and then Sandhurst Military Academy. He did see service on the Western Front in 1914 as a lieutenant, was wounded in the foot but later promoted to second lieutenant, and was awarded the Military Cross in recognition of “an act or acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy on land”. He did box and swordfight for the army, indicating that perhaps Hubbard’s tale of Macbean rattling sabres and trading blows with the Italian “Giovinni” may hold some truth.

In 1916, Macbean, by now a trained cypher, was moved quietly to Salonika, in Greece, on secretive business there, as well as in Baku, Azerbaijan. For this he was raised to captain, then major and awarded both the French Croix de Guerre and the Serbian White Eagle (5th Class) medals. He married Bedells in 1918 and they had two children.

Then more mystery: postings that hint at espionage and clandestine work. A stint in Ulster during the Irish civil war, a posting in Egypt with time spent in Cairo and Alexandria, and then, in early 1927, the offer of a temporary cypher officer job in Beijing at £500 a year (about £33,000/US$40,000 today). It was not a great wage, not enough to take the family to China (although Phyllis’ career kept her in London) and not the salary of a “regional head” of MI6, as Hubbard would have his readers believe.

The job lasted three years or so and Macbean returned to England in the autumn of 1931 to take up a new job as a travel agent – not the usual career pattern of a senior British intelligence officer. Macbean rejoined the army in 1939, when Britain declared war on Germany. However, he was soon invalided out, returned home and after a period of illness died in 1944.

Whether Major Ian Macbean ever remembered the teenaged American boy he’d somehow met in Beijing in 1928, we will never know. Perhaps he told the lad some tall tales that the imaginative L. Ron was only too keen to soak up and embellish. But however much fact and fiction got mixed up over the years, however much Hubbard’s tall tales of his China sojourns have been dismissed, at least the story of Major Ian Macbean was true. Which inevitably makes you wonder about all those Cantonese pirates, Italian swordsmen, Mongolian bandits, Siberian shamans and even Old Mayo, the Chinese magician. They may all be out there just waiting for us to find them again.

Of course, we can’t help but wonder, did the teenage L. Ron Hubbard experience anything in China that inspired his later self-concocted beliefs and helped shape his cult? Otherworldly powers, immortality, the echoes of Asian philosophies in his concept for Dianetics, the canonical text of his religion?

Perhaps amid the shamans and magicians there was a moment while he was on the Great Wall near the Juyong Pass that may have led him to his future – many would say delusional – grandeur.

In his journal he wrote: “The wind whipped through my hair and stung my cheeks with its bitter breath. It shrieked about the lonely tower, screamed to frighten me away from its playthings, the Wall, the mountains and the thorns. And I laughed to match its wildness and opened my blue shirt at the throat to flaunt the wind-god and ridicule his power.”